National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs)

National Energy and Climate Plans (in short NECPs). What are they? Why do we have them? And what happens to them after 2030? Find out in the article below.

In this article, we break down what the National Energy and Climate Plans are, what is their content and why we have them.

What are the National Energy and Climate plans?

National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) determine national contributions of each Member State towards the binding EU energy-climate targets and the objectives of the Energy Union, over a period of ten-years. Each NECP describes the foreseen energy–climate measures and policies to be implemented over this period to reach the proposed national targets.

The NECPs are mandated by the Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (in short, the Governance Regulation). The Governance Regulation is part of the “Clean Energy for all Europeans” Package. According to the Governance Regulation, the energy-climate objectives, national targets and contributions included in the NECPs are non-binding. The only exceptions are the binding national targets on annual greenhouse gas emission reductions over the period from 2021 to 2030, determined by Regulation (EU) 2018/842. Regulation (EU) 2018/842, also called the “Effort-sharing Regulation”, continues the approach of annually binding national limits on greenhouse gas emissions set in Decision No 406/2009/EC (also called the Effort-sharing Decision containing the ‘20-20-20’ targets). [1]

The ‘’first round’’ of final NECPs with a 2030-horizon (covering the period 2021 to 2030) had to be submitted by the Members States by 31st December 2019. Before that, EU Member States had to submit their draft NECPs by 31st December 2018. Subsequently, the European Commission published its assessment of these 28 draft NECPs in June 2019 (COM/2019/285), supported by the Commission’s policy scenario EUCO3232.5.

Please refer to the European Commission website for the complete list of the NECPs and relevant documentation.

What is included in a National Energy and Climate plan?

NECPs represent the direction national policymakers intend to follow in the next decade, providing thereby a credible and stable signal to public and private actors. NECPs cover the five dimensions of the Energy Union:

- Decarbonisation (including Renewable Energy Deployment)

- Energy Efficiency

- Energy Security

- Internal Energy Market

- Research, Innovation and Competitiveness

In order to account for these dimensions and propose a sufficiently detailed strategy, different types of measures are prescribed in the NECPs. Some examples of measures are the following: technological deployment targets, technological research and innovation objectives and funding targets, national energy policy tools, increasing interconnection infrastructure with neighbours and regional cooperation, financial support measures and enhancement of emissions removals (e.g. through Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry). NECPs also cover sectors that are not regulated by the EU Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) and are present in the Effort-sharing Regulation, including transport, buildings, agriculture, non-ETS industry and waste.

Within an NECP, national governments are free to flexibly put emphasis on specific sectors, technologies and national energy policy choices. The different national approaches put forward in the NECPs highlight the diversity of possible energy transition strategies available, both in terms of policies and technologies. Some plans put a greater emphasis on technologies such as renewable electricity, hydrogen or electric vehicles; others offer insights into possible measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions in hard-to-abate sectors (e.g. industrial activities).

Additionally, NECPs should also provide an analysis of the estimated macroeconomic effects of the planned policies and measures. When possible, also an analysis of the impacts of the policies on health, environment, employment, education and society as a whole, should be included. Analysing the different areas affected by the NECPs leads to understanding which areas (and which citizens) could be impacted adversely by a low-carbon economy

It is relevant to mention that the “Aarhus Convention” – which entered into force in 2001- requested that the public’s views are also to be consulted and integrated into the preparation of the NECPs.

Why do we have National Energy and Climate plans?

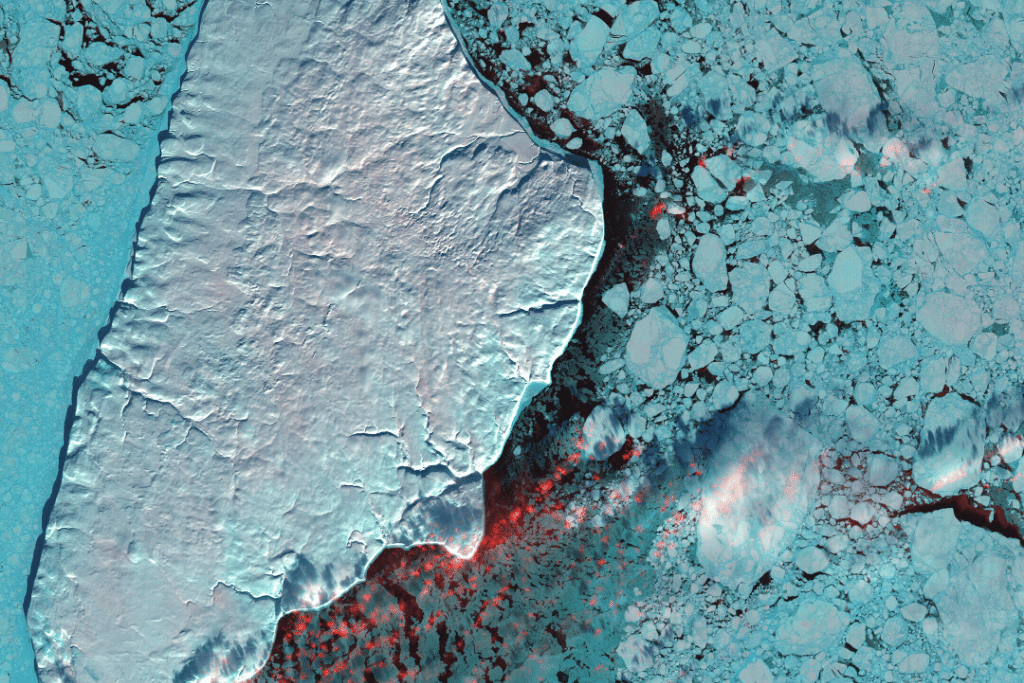

The integrated National Energy and Climate plans are related to the long-term objectives of the Energy Union and the long-term EU commitments made at the Paris Agreement commitments. More precisely, the 2030 Climate & Energy framework sets binding EU-targets on a 2030-horizon, which were used as a basis to set the EU’s nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement. The achievement of the 2030 and long-term objectives and targets of the Energy Union in line with the Paris Agreement commitments is ensured by the Governance Regulation. The Governance Regulation sets out the necessary legislative foundation for the governance mechanism mandating NECPs. The ‘’first round’’ of NECPs, in turn, shows how each Member State does its part to jointly reach the 2030-horizon targets. These binding EU 2030-horizon targets are:

- at least 40% cuts in greenhouse gas emissions (from 1990 levels);

- at least 32% share for renewable energy in final energy consumption;

- at least 32.5% improvement in energy efficiency, relative to ‘business as usual’ projections [2], and;

- at least 15% electricity interconnection target, relative to the share of national electricity production that interconnectors deployed should allow to be transported towards neighbouring countries.

Additionally, the governance mechanism regulating NECPs sets a transparent iterative process of monitoring and recommendations between the Member States and the European Commission. The ambition, completeness and quality of the draft NECPs for 2030 were assessed by the European Commission both at an aggregated level and country-specific level.[3] This was done to verify if these plans were well-founded and if their aggregated contribution would not underachieve the EU 2030 targets. After the adoption of the final NECPs, every two years each country must publish a progress report, which will allow the European Commission to supervise the overall EU progress towards these targets.

In order to account for “significant changing circumstances”, the NECPs should be updated once over the ten year period. For the “first round” of NECPs, Member States should submit a draft and a final version of their updated plans respectively by 30th June 2023 and 30th June 2024. Objectives, targets and contributions should only be modified if they lead to an increased overall ambition.

It is important to add that based on an assessment of these NECPs (and their updates) the European Commission can identify needs for additional EU energy policies and measures. More precisely, Art. 31(3) of the Governance Regulation states that “Where […] the Commission concludes that the objectives, targets and contributions of the integrated NECPs or their updates are insufficient for the collective achievement of the Energy Union objectives and, in particular, for the Union’s 2030 targets […], it shall propose measures and exercise its powers at Union level in order to ensure the collective achievement of those objectives and targets.”

What happens after 2030?

The development of the NECPs acts as a planning tool towards the climate-neutral ambition of the European Union in 2050 (the “European Green Deal”).

The governance mechanism described above goes beyond 2030. Namely, before the start of the next “round” (2030) and every 10 years thereafter, each Member State will develop again their own NECP. The iterative process of assessing draft and final NECPs, in addition to demanding an update in the NECPs and monitoring the progress reports, is also valid beyond 2030, for the successive “rounds”.

Please note that in that regard, in addition to the NECPs, also complementary national long-term strategies with a perspective of at least 30 years (so a 2050-horizon for the first “round” of national long-term strategies) were due to be delivered by the Member States by January 2020 as part of the Governance Regulation.

Both the integrational NECPs and the national long-term strategies should be prepared and submitted every 10 years. Whereas the update of the latest notified NECPs should be delivered by 30 June 2024 and every 10 years thereafter, the national long-term strategies will be, where necessary, updated every five years.

Notes:

[1] The Effort-sharing Regulation complements the reduction in EU emissions covered by EU ETS and the contributions by Land use, Land-use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation, enabling the achievement of the EU climate targets for 2020 and 2030.

[2] These ‘business as usual’ projections refer to an EU primary energy consumption of 1887 Mtoe by 2030 and to an EU final energy consumption of 1416 Mtoe by 2030. However, due to the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britany and Northern Ireland from EU, the Decision (EU) of 19 March 2019 on Amending Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency and Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action amended the EU projected energy consumption figures, Therefore, the EU-27 primary energy consumption and final energy consumption by 2030 should respectively be no more than 1128 Mtoe and 846 Mtoe. In 2018, according to Eurostat, the EU primary energy consumption and final energy consumption were respectively 1552 Mtoe and 1124 Mtoe.

[3] The Commission published a Communication on the draft integrated NECPs can be found at the following link.

If you still have questions or doubt about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Piero Dos Reis, Golnoush Soroush.

Relevant links

FSR training course

The European Energy Transition: Actors, Factors, Sectors

Introduction to Climate Governance (no longer running)

Regulation and Integration of Renewable Energy

Electric Vehicles: a power sector perspective

Publications and web resources

- Energy regulation towards decarbonisation

The challenge of net zero – Topic of the month: energy regulation and decarbonisation

How many shades of green? : an FSR proposal for a taxonomy of ‘renewable’ gases

- Energy policies towards decarbonisation

The EU Clean Energy Package (ed. 2019)

How far should the new EU Methane Strategy go?

New business models in electricity: the heavy, the light, and the ghost

- Climate policies towards decarbonisation

Informing the carbon market policy dialogue : the emissions trading systems at a glance

- Technological innovation towards decarbonisation

Molecules: indispensable in the decarbonized energy chain

Potential disruptions in the energy sector. Why should we be thinking about that?

Charging up India’s electric vehicles: infrastructure deployment and power system integration

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights