Hydrogen certification

What is certification? Why is certification important for the hydrogen economy? How does certification work? What are the future challenges for certification? Learn the basics and dig deeper with this article.

We know clean energy is key to decarbonising the economy, but what does ‘clean’ mean? And how can consumers know that the product they purchase is truly clean? In this ‘Cover the Basics’ article we explore the subject of clean energy certification through the case of clean hydrogen, an important energy vector in meeting the aims of the EU Green Deal.

What is certification?

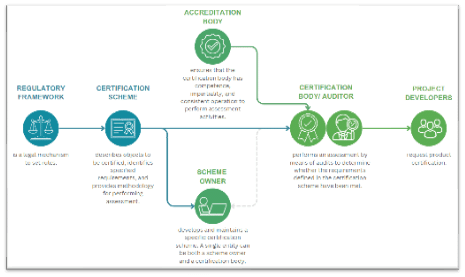

On a conceptual level, certification may be defined as the process through which a third party provides independent assurance that a product meets specific requirements. The certificate then proves the characteristics that may not usually be detected through inspection of the good itself. Certification therefore allows the creation of a market for a premium product – think of Fairtrade coffee or chocolate, for instance.

For hydrogen, the certificate reflects greenhouse gas emissions (such as methane) and other sustainability requirements established by EU law. To qualify as RFNBO hydrogen, for instance, the hydrogen production must result in a 70% reduction of GHG emissions, compared to its fossil equivalent. Moreover, the hydrogen must be produced with renewable energy. The power plant must be ‘additional’ and both geographical and temporal correlation requirements apply. Compliance with these complex requirements may be reflected in a certificate.

Why is certification important for the hydrogen economy?

Most obviously, renewable or low-carbon hydrogen will come at a premium price, and customers will want to be certain they are acquiring a product matching the price tag. Still, this raises the question of why customers would be willing to pay this premium in the first place. Several drivers may be identified.

First, a certificate assures the customer that the product meets certain sustainability requirements (such as GHG emissions). This may be relevant to reduce the customer’s Scope 2 and 3 emissions on a voluntary basis.

Second, the consumption of renewable hydrogen may be required to meet mandatory targets. For instance, the Third Renewable Energy Directive introduced quotas for transport and industry. Similarly, certification of the hydrogen’s carbon footprint may be required to mitigate CBAM charges upon import to the EU.

Third, government support may depend on the certification of the hydrogen. For instance, the EU Hydrogen Bank only finances the production of RFNBO-compliant hydrogen. The EU Taxonomy may also be mentioned in this respect.

How does certification work?

A hydrogen producer wishing to prove that their hydrogen is compliant, for example with the Renewable Energy Directive, must do so through independent and transparent audits. Member State authorities will then assess compliance and may require further documentation or inspections. Given the level of complexity and detail these assessments require, it is not guaranteed to be a smooth process. Furthermore, this may need to be repeated in every Member State where the hydrogen is consumed.

As an alternative to this case-by-case approach, hydrogen producers could opt for certification through a voluntary scheme officially recognised by the European Commission.[1] Within this framework, certification companies (such as TÜV SÜD or Bureau Veritas) assess independently whether the hydrogen complies with both EU law and the scheme rules. The major benefit of employing the services of an officially recognised voluntary scheme is that all Member State authorities must accept the certificates issued under this scheme as complete proof of the sustainability requirements imposed by EU law. This significantly reduces uncertainty, bureaucracy, and streamlines international trade.

What about hydrogen imports?

Besides domestic production, the EU will also depend on the import of clean hydrogen (derivatives) produced in areas where solar and wind energy is more abundant, such as Latin America, the Middle East or even Australia.[2] Hydrogen (derivatives) can be imported freely but counting them towards regulatory targets will still require compliance with EU laws on RFNBO. In order words, the sustainability requirements apply equally to both hydrogen produced inside and outside of the EU. The Delegated Acts on RFNBO contain detailed criteria which are designed for and refer to the EU energy system (such as bidding zones, curtailment, ETS, guarantees of origin…).[3] For producers located outside of the Union, it could be especially difficult to prove compliance with these criteria, as a local equivalent would need to be established.[4] Here, a voluntary scheme could step in to facilitate imports, by offering a framework already recognized by the European Commission. This would offer certainty to producers and investors alike. In sum, hydrogen imports could also greatly benefit from certification through a voluntary scheme.

What are the future challenges for certification?

Certification is a crucial tool to facilitate trade in renewable and low-carbon hydrogen. It holds the potential to connect jurisdictions globally, even if they have separate standards relating to GHG emissions and sustainability requirements for hydrogen production.[5] Certification could offer the common language to report compliance with these divergent criteria, without necessarily requiring further harmonisation on standards. At the very least, this would necessitate transparency on the GHG emissions accounting methodology.

A digital product passport could accompany the hydrogen along the value chain, and information could be added to it in a modular approach.[6] This process could be made fully automatic and digitized through the use of blockchain.[7]

A robust certification system for hydrogen could also be used beyond the hydrogen value chain. It could be envisaged to follow the consecutive transformations the energy undergoes. For instance, the renewably produced electricity could receive a certificate, which is then transferred to the hydrogen. Next, the renewable hydrogen could be used to produce sustainable steel, and this could be certified in a similar fashion.

Conclusion

Renewable and low-carbon hydrogen has been and probably will remain a hotly debated topic in EU energy policy. Different standards on GHG emissions and other sustainability requirements proliferate, both in the EU and globally. Certification (also through voluntary schemes) is key in providing credible assurance that the hydrogen meets the relevant standard.

If you still have questions or doubts about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Further reading

[1] A scheme may also be set up by a Member State, but currently there is no such candidate for hydrogen. For simplicity, these are therefore omitted from this article. For biofuels, only one national scheme exists, see the Austrian Agricultural Certification Scheme (AACS).

[2] See the EU Hydrogen Strategy and REPowerEU plan.

[3] European Commission, Q&A Implementation of hydrogen delegated acts, version 14 March 2023, Annex, p. 19-23.

[4] F. Gallegos Aguirre, The Art of Certifying Hydrogen: A New Era in International Trade, OGEL 2024, vol. 22, issue 3, , 17-18.

[5] German Energy Agency/World Energy Council – Germany (publisher) (dena/World Energy Council – Germany, 2022), Global Harmonisation of Hydrogen Certification, Berlin 2022.

[6] IEA (2023), Towards hydrogen definitions based on their emissions intensity, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/towards-hydrogen-definitions-based-on-their-emissions-intensity, 74.

[7] See for the German research project HydrogenChain, https://www.hydrogenchain.de/en/.

Quick links

A ‘no-regrets’ network for EU hydrogen? Event Highlights

Mapping the new global geographies of clean hydrogen value chains Event Highlights

Five reflections on clean hydrogen’s contribution to European industrial decarbonisation from 2024 to 2030 Policy Brief

Certification of Hydrogen Imports: Which Requirements, Which Perspectives? Event recording

Training

Executive Course to master European Hydrogen Legislation

Clean Molecules for the Energy Transition

Specialised Training on the Regulation of Gas Markets