A first look at REPowerEU: The European Commission’s plan for energy independence from Russia

In this article, James Kneebone and Ilaria Conti give some immediate reflections and analysis on the May 18 REPowerEU Plan, summarising and contextualising its content in the process.

Yesterday, May 18, 2022, the European Commission published its ‘REPowerEU’ plan outlining the EU’s path to energy independence from Russian fossil fuels by 2027. In his presentation of the Plan following its adoption at the meeting of Commissioners earlier the same morning, Executive Vice-President Timmermans characterised the Plan in the following terms “In March we showed it could be done, European Council in Versailles decided it should be done, today we show how it will be done.”

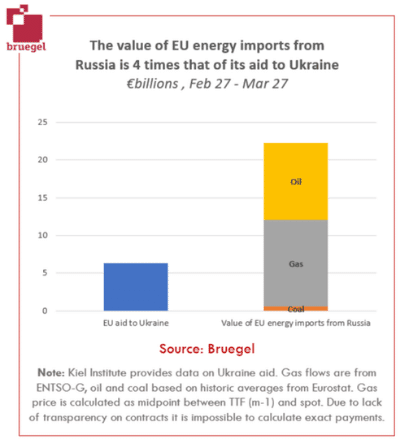

The publication was a follow-up on the first ‘REPowerEU’ document from March 8, 2022, where the Commission began outlining steps to avoid Europe’s energy dependence on Russia being weaponised against the bloc. The urgency of the issue was prompted by the recent invasion and continued aggressions of Russia in Ukraine, as well as the subsequent disconnection of Poland and Bulgaria from Russian gas deliveries earlier this month. REPowerEU also sits thematically within the backdrop of wider efforts to hinder Russian war efforts in Ukraine through cutting off key revenue streams, including existing sanctions on coal and the banking sector.

In this short article we will give some immediate reflections and analysis on the May 18 REPowerEU Plan, summarising and contextualising its content in the process. Along with the REPowerEU flagship document, the Commission presented several other satellite strategies and guidance documents which correspond to the aims of the main text.

[References to these other documents are present throughout the following article, but links to their full texts can be found at the bottom of the page.]

Charting a path: Short, mid, and long-term aims

The central aim of REPowerEU is twofold:

- Ending Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels as quickly as possible, in principle by 2027, with a 2/3 cut in Russian gas consumption by the end of 2022.

- Securing the long-term sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and energy supply to the EU energy system through a controlled departure from this long-entrenched relationship with Russia.

Achieving these goals will require a combination of short, mid-term, and long-term targets and measures covering the following three pillars: (i) demand reduction, (ii) diversification of suppliers for conventional (fossil) fuel imports whilst future–proofing the corresponding infrastructure, (iii) acceleration of the transition to renewable energy sources. The timeline and level of ambition are such that the speed and scope of action will have to go far beyond the already ambitious proposals outlined to date, for example under the ‘Fit for 55 Package’ and the ‘Hydrogen and Decarbonised Gas Market Package’. To some extent, this is akin to a war-economy level of mobilisation.

1. Demand reduction: Short-term measures

“The cheapest energy is the energy you do not use”, this was the message of Mr. Timmermans at the readout of the Commissioner meeting on May 18. Avoided demand and energy efficiency measures are not only the most cost-effective measures, but also the most sustainable, secure, and the most immediately actionable response available. The EU Member States pay roughly €1billion per day to Russia for fossil energy deliveries at the exceptionally high current fossil energy prices. Lowering demand will immediately be reflected in lower payments, lower overall market prices, an easing of pressure on availability concerns during the gas filling season, and ultimately lower emissions from a reduction in the combustion of fossil fuels.

With this in mind, the following measures are proposed:

- Increase the binding ‘Energy Efficiency Directive (EED)’ target to 13% from 9%.

- Further support renovation of buildings through the ‘Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD)’.

- A ‘Playing my part’ plan in cooperation with the International Energy Agency (IEA) to support individuals in reducing their personal energy demands.

- Recommendations to Member States on lowering energy demand, such as reduced VAT rates for high efficiency heating systems, building insulation, and other energy pricing measures which encourage switching to heat pumps and purchase of more efficient appliances.

- Guidance on ‘National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs)’ for the 2024 submission focused on planning and the reduction of fossil fuel usage.

- Drive to electrify fossil sectors, with a focus on energy intensive industries and the transport sector, for example through possible legislation on zero-emission cars in public and corporate fleets.

- Implementation of the ‘EU Save Energy Communication’, also released on May 18.

- In the most extreme cases, the preparation of contingency plans for the curtailment of non-protected customers.

2. Diversifying imports of conventional (fossil) energy and future proofing infrastructure: Short to mid-term measures

Even with aggressive energy demand reduction in the short-term, and mid to long-term plans for a near-totally decarbonised energy system, there will be a requirement for fossil fuels from non-Russian partners. The Commission prioritises gas in this area for a couple of important reasons.

Firstly, it is the least liquid market of the fossil sectors, therefore providing the most important scope for pooling EU buying power in the market to attract deliveries at the lowest possible cost. Getting the best gas price possible is also key for keeping electricity costs down for consumers, due to the role of gas in price setting in the electricity market (see here).

Secondly, gas infrastructure is perceived to be the most flexible to the use of other non-fossil molecules in the future energy system, namely hydrogen and ammonia. For example, the Commission believes that new liquid natural gas (LNG) terminals could be made in such a way that they could receive renewable molecules. In this way, the EU is offering what it considers to be a double utility to potential energy partners: fossil gas purchases delivered through LNG terminals in the short-term, followed by renewable gas deliveries in the long term. This is one way of avoiding the risk of stranded assets that would otherwise come from investing in fossil-only infrastructure that is not compatible with a Net-Zero future.

What we’re proposing…is what I would call a double deal: first a short-term deal to provide us with the fossil fuel that we need, and then a long-term deal to incorporate them in a global system on the production and use of green hydrogen

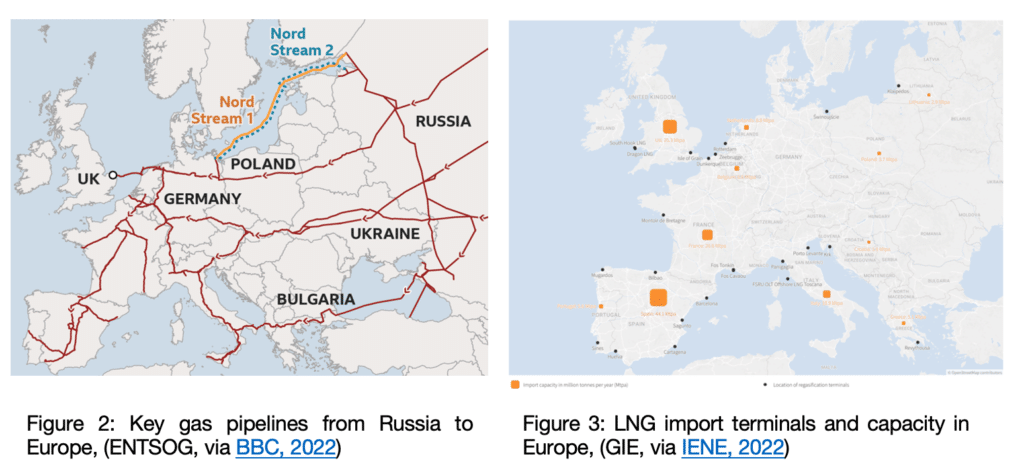

Shifting to ports for molecular energy imports is based primarily on infrastructural flexibility. The vast majority of Russian gas consumed in the EU is delivered by a network of pipelines directly connecting the two territories, an inflexible form of infrastructure that doesn’t allow for trade in flows with other exporters and importers. There are 21 liquid natural gas (LNG) terminals in the EU, which can receive deliveries from anywhere in the world, effectively decoupling infrastructural buildout from the weaponisation of energy flows. However, the distribution of LNG terminals in the EU is not consistently aligned with demand centres and are therefore constrained by the interconnection capacity of the grid in strategic places. For example, the Iberian Peninsula hosts 1/3 of the terminals, and has considerably more capacity than the region requires for its own needs. However, there is only one gas interconnection between the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of the Continental grid, limiting the scope for sharing gas with key EU demand centres such as Germany – which currently has no LNG terminals at all.

With this in mind, the following measures are proposed:

- An ‘EU Energy Platform’ for the voluntary common purchase of pipeline fossil gas, LNG, and hydrogen. The Platform is also set to be open to Energy Community Members (Western Balkans, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia).

- An ‘External Energy Engagement Strategy’ to support the fostering of long-term relations with new energy partners premised on the transition to the delivery of renewable energy vectors, also published on May 18.

- Efforts to diversify nuclear value chains away from Russia and towards domestic alternatives or other global partners.

- Reinforcement of the Southern Gas Corridor and connection of central Europe and northern Germany with LNG import points.

- Targeted investment in oil infrastructure within regions particularly dependent on Russian pipeline imports, namely via the Druzhba pipeline, as well as the upgrading of facilities to process non-Ural crude oil.

- Fulfilment of the electricity network buildout projects within the 5th ‘Important Projects of Common European Interest’ (IPCEI) list.

- Acceleration of key interconnection points in the electricity grid, namely between France and Spain, as well as within the Baltic region, with a view to ensuring electricity trade and system operation cannot be used to undermine energy security beyond 2025.

- Obligation to fill gas storages to 80% by 1 November 2022 each year.

- Facilitate cross-border gas reverse-flow capacity between the Member States and conclude bilateral solidarity arrangements to protect against supply disruptions.

3. Accelerating the clean energy transition: Mid to long-term measures

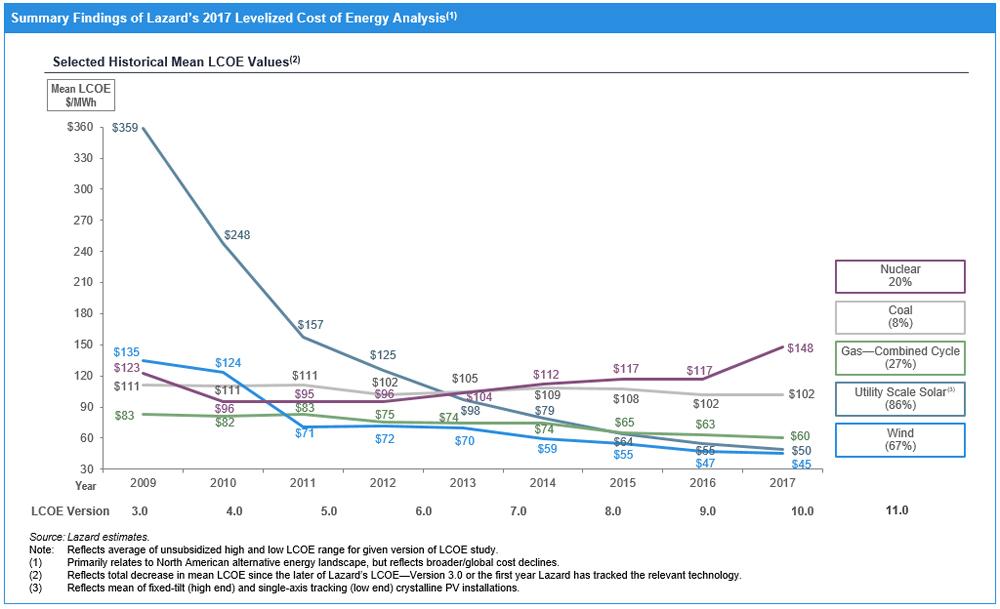

The mid to long-term arm of the strategy is to bring much of energy generation within the EU’s borders through renewable sources, coupled with renewable import capacity to cover the remaining energy requirements. Both electrons and molecules will be required to meet the different energy needs of the economy, this means direct consumption of renewable electricity where possible, as well as the subsequent conversion of these electrons into renewable gases and liquids where required. In both cases, the starting point remains the same, massive quantities of renewable electricity, delivered consistently and at low prices. The required deployment of renewable generation goes far in excess of what has been achieved to date in the sector, and recent modelling suggests it is virtually impossible for the EU to ‘overbuild’ renewable electricity generation capacity at this point.

The drawing of sustainability priorities into the forefront of security and competitiveness agendas is a hugely symbolic moment for the formation and prevailing landscape of EU energy policy. In contemporary history, all three aspects have characterised an interconnected but broadly independent trifecta of policy aims, with each given priority at different points in time.

As Executive Director of the International Energy Agency (IEA) Fatih Birol recently asserted during the State of the Union, “Since February 24…we are in a new energy world and there is no way back.”. The sustainability agenda is now the security agenda and the competitiveness agenda, with cheap and reliable, largely domestic renewable electricity at the foundation.

Within this context, sustainability-focused measures form the core of the REPowerEU text and corresponding initiatives.

The following measures are proposed:

Renewable electricity generation and technology

- Increase the target in the ‘Renewable Energy Directive’ (RED) to 45% by 2030, up from 40% under the Fit for 55 Package.

- Target 320 Gigawatts (GW) of solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity installed by 2025 rising to 600 GW by 2030.

- Double the number of heat pumps in use to 10 million over the next 5 years, including corresponding measures to utilise waste heat from industry and engage in community heating projects.

- Enhance the regulatory framework and life-cycle sustainability of solar PV by tabling eco-design and energy labelling requirements in Q1 2023, as well as revising existing requirements for heat pumps by the same date.

Hydrogen

- Target 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen production in the EU and the same quantity of imports by 2030.

- Align the sub-targets for renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs) under the RED for industry and transport with the REPowerEU ambition (75% for industry and 5% for transport).

- Double the number of hydrogen valleys through Hydrogen Joint Undertaking.

- Proposal of two Delegated Acts on (i) the definition of renewable hydrogen production as well as (ii) defining a methodology for calculating greenhouse gas emissions of different production methods. Both are open for public consultation until June 17, 2022.

- Regular reports on uptake of renewable hydrogen in key sectors starting in 2025.

- Mapping hydrogen infrastructure needs by March 2023.

- Scale-up of electrolyser manufacturing, details outlined in the ‘Electrolyser Declaration’.

Biomethane and biogas

- Target 35 billion cubic metres (BCM) of biomethane production by 2030.

- Establish biogas/biomethane partnership as well as corresponding incentives for its production, coupled with the preparation of infrastructure for its integration into the supply chain on a large scale.

- Supporting research, development, and innovation.

- Release of ‘Biomethane Action Plan’ on May 18.

Bottlenecks and corresponding measures

The Commission foresees considerable challenges associated with such ambitions under such a timescale, here we will take a brief walkthrough three key structural challenges in place, and what measures are targeted at alleviating those bottlenecks – namely associated with permitting, critical raw materials, and the workforce.

Permitting

As remarked upon by Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen, Commissioner Kadri Simson, and Executive Vice President Frans Timmermans during the presentation of the Plan – permitting for solar projects can take up to two years and wind farms can take up to nine, far too long under current conditions. There are three key measures targeting this problem.

Firstly, the introduction of the ‘European Solar Rooftop Initiative’ which aims to make rooftop solar infrastructure mandatory for commercial and public buildings by 2025, and residential buildings by 2029. This overcomes much of the permitting and planning issues associated with solar farms, as well as alleviating pressure on the transmission and distribution grids by localising production. Secondly, the identification and promotion of ‘go-to areas’ for renewable energy infrastructure, where fast-tracked permitting and planning time is reduced to less than 1 year without foregoing environmental due diligence. This is made possible by the recognition of renewable energy as in the ‘overriding public interest’. Thirdly, the Commission is proposing a formal Recommendation on permitting procedures to support effective and timely administrative procedures through sharing of best practices, and regional cooperation.

More widely, the administrative processes for IPCEI’s are set to be accelerated for renewable energy infrastructure, including those concerning hydrogen value chains. Moving forward, these IPCEI’s will also benefit from revised methodologies and additional administrative resources and guidance for their assessment.

Raw materials

The war in Ukraine, compounded by general global supply shortages due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a recent rebound in economic activity in many parts of the world has created shortages for certain critical raw materials, many of which are necessary for the energy transition. REPowerEU takes both a short-term and long-term view on this.

- Firstly, in the short-term the EU is working to diversify its supply sources through strategic partnerships, including via ongoing Free Trade Agreements, as well as pooling the influence of certain commercial EU stakeholders to reclaim more of the supply chain and better compete at an international level, for example through the EU ‘Solar Industry Alliance’.

- Secondly, moving forward the Commission proposes to prepare legislation on critical raw materials as well as ensuring circular economies are prioritised in the buildout of new infrastructure, and therefore materials can be recovered and reused multiple times.

Workforce

Under current conditions there are certain cost-effective and attractive technology swap solutions available to consumers that would help support key aims of the REPowerEU framework, such as heat pumps as an alternative to gas boilers. However, there are limitations on speed of uptake due to the unavailability of appropriately trained staff to install, manage, and maintain the infrastructure. The same problems are also evident at larger scales, such as for natural gas to hydrogen switching. Measures in REPowerEU look to target these bottlenecks through channelling resources into three training initiatives, the ‘Pact for Skills’, ‘ERASMUS+’, and ‘Joint Undertaking on Clean Hydrogen’.

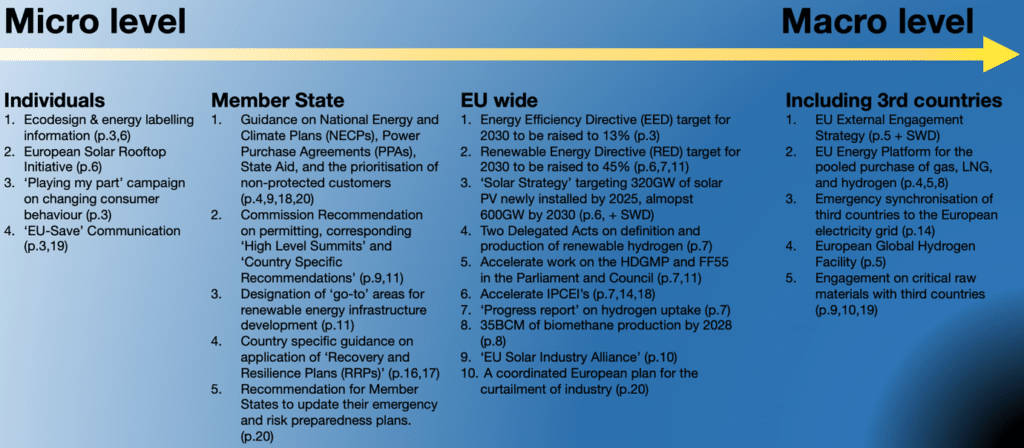

Mapping the levels of intervention

The following figure looks to map many of the key measures mentioned above according to the level of intervention, illustrating how this range of initiatives looks to leverage actors at all possible levels.

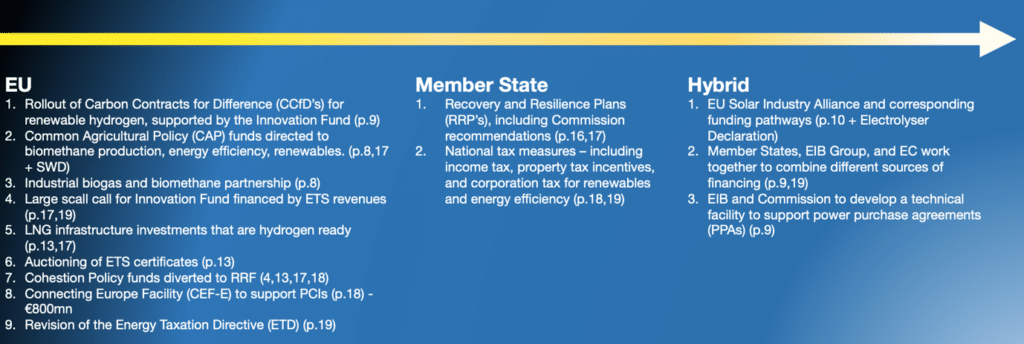

Financing

The financial implications of such a transition have not been hidden by the Commission, nevertheless, the evolution should yield significant cost-savings within a relatively short period. The estimates are…

- Overall spending associated with the measures in the Plan totals roughly €300bn, with €225bn in loans and €75bn in grants. €210bn to be spent by 2027, rising to €300bn by 2030.

- Roughly €12bn in fossil assets: €10bn earmarked for LNG and strategic pipeline gas infrastructure, with an additional €2bn for targeted oil developments.

- Savings from avoided purchasing of oil, coal, and gas could amount to roughly €100bn per year.

In terms of funding sources, there are a combination of measures leveraged – covering allocation of public funds earmarked for COVID recovery (RRF), to research and innovation budgets (Horizon Europe), to the sale of emission credits under the Emissions Trading System (ETS), and beyond. The figure below maps many of these initiatives, according to the actors coordinating them.

The clear message from these initiatives is that the EU is shifting the energy strategy focus from commodity costs towards infrastructural investments, with 95% of funding targeted at renewable infrastructure. This is a fundamentally different way of viewing costs associated with our energy system. For comparison, several EU governments have recently made blanket relief payments to support consumers in the purchasing of fossil energy, for example Belgium provided relief measures to its citizens totalling €1.3bn. These are pure costs, and the money spent disappears with the combustion of the fuels. Spending on infrastructure that continues to harvest energy at near zero marginal cost for years and years is an investment. Both forms of measures may be required in the short to mid-term, but the overall direction of travel is clear.

Conclusions and reflections

This commentary article comes only one day after the publication of the RePowerEU Plan, which makes drawing definitive conclusions and reflections challenging and perhaps premature. Nevertheless, as a first reaction, we would like to acknowledge that the REPowerEU Plan is further confirmation that the Commission is taking very seriously its role as a major actor in the current geopolitical energy landscape. In response, concerted and detailed efforts are being made towards a complete reconfiguration of key energy pathways. Although new and radical in many ways, the overall themes are consistent with established energy aims. Crucially, this new energy landscape reconciles the three longstanding pillars of European energy policy (i) affordability and accessibility, (ii) sustainability, and (iii) security of supply, into one coherent long-term pathway.

Despite the clarity of the overall trajectory, there have been some critiques of the Commission’s approach to fulfilling these aims in the short to mid-term, often revolving around risks of undermining priorities in other important sectors. One example regards the planned aggressive ramp-up in biomethane production, which analysis suggests could pose a risk to food security through creating competition for crops. Another potentially problematic point in this regard is funding streams, where the opportunity cost of redirecting large quantities of, for example, RRP and Cohesion Policy funds could result in gaps elsewhere. Remaining with funding, there are question marks over how realistic it is to use LNG terminals for the import of renewable hydrogen or ammonia. This brings into doubt the credibility of assurances that investments in this area won’t become stranded and that fossil fuel lock-in from this infrastructure can be effectively avoided.

Certain stakeholders are also concerned that the focus on green hydrogen in general is excessive in the absence of strong wording on additionality criteria, creating a meaningful risk of cannibalising scarce renewable electricity resources and leading to higher overall emissions in the sector. In a similar vein, the import of large quantities of renewable hydrogen should be accompanied by strict and transparent standards for its production and transportation. The two Delegated Acts opened for consultation will go a long way to defining these conditions. Finally, the somewhat revolutionary proposal to launch an EU energy platform for the voluntary common purchase of pipeline gas, LNG and hydrogen has been raising some legitimate questions concerning timing of implementation and its overall functioning.

Broadly speaking, the REPowerEU Plan paints quite a comprehensive picture of EU energy policy long-term, and to a considerable extent assures the longevity of the now unified EU energy policy aims. This is achieved through ambitious proposals to accelerate investment and buildout of renewable electricity generation and value chain infrastructure, which are now on the table and awaiting implementation. However, the incredibly short timeframes set to achieve independence from Russian fossil fuels has suddenly and dramatically raised the level of the short-term challenge, particularly as regards securing alternative fossil fuel sources in the immediate future. The greatest test for implementation will undoubtedly come in the first months and years and will require the combined efforts of stakeholders at all levels.

The FSR continues to contribute research, advanced training, and facilitate policy dialogue on the energy transition and wider decarbonisation drive. Moving forward, FSR remains eager and committed to engaging in evidence-based policymaking that supports the EU’s energy security, affordability, and climate ambitions.

Other strategies, texts, and guidance documents published in connection to REPowerEU

- EU Save Energy Communication

- EU External Energy Engagement Strategy

- EU Solar Strategy

- Recommendation on permitting procedures and Power Purchase Agreements

- Proposal for a Regulation on REPowerEU chapters in recovery and resilience plans

- Guidance on recovery and resilience plans in the context of REPowerEU

Other relevant FSR publications

- FSR Cover the Basics – Hydrogen

- FSR Fit for 55

- FSR Hydrogen and Decarbonised Gas Market Package

- FSR Knowledge platform

- FSR Gas storage solutions proposal

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights