Unbundling in the European electricity and gas sectors

Unbundling in the European electricity and gas sectors. What is it and why is it important? Our experts explain.

What is unbundling?

In the regulation of network industries – like electricity or gas – unbundling refers to the separation of the activities potentially subject to competition (such as production and supply of energy) from those where competition is not possible or allowed (such as transmission and distribution – for in the EU, transmission and distribution of electricity and gas are regulated monopolies). The introduction of unbundling implies that an actor performing a competitive activity is constrained and eventually prevented from also performing a monopolistic activity (i.e. not allowed to bundle these two different types of activities).

Determining the adequate level of unbundling of the monopolistic network companies from the companies performing competitive activities is of major importance when discussing regulatory models. Unbundling is an example of a topic that is discussed in more depth in the FSR Annual Training on the Regulation of Energy Utilities.

Why is unbundling important in the energy sector?

In the electricity and gas sectors, the physical network that connects generators of electricity or producers of gas to consumers represents an essential facility. Access to the network is fundamental for anyone willing to sell or buy energy at reasonable costs; at the same time, the duplication of the existing infrastructure is either impossible or extremely expensive.

A firm controlling the network and involved also in the competitive segments of the supply chain has then an obvious interest in limiting or deny access to the other firms active upstream or downstream. Therefore, ensuring access on a just, transparent and non-discriminatory basis to any market player is a first and necessary step to achieve effective competition in the sector.

However, this first step is usually not enough to guarantee fair competition and here is why. Even if obliged to grant third party access (TPA) – possibly on a regulated rather than negotiated basis – the firm controlling the network can still benefit from a non-level playing field. In particular, it may delay the expansion of the grid in the presence of congestion that segments the market and keeps at bay one of its competitors. Alternatively, it may cross-subsidise one of its businesses subject to competition – as for instance supply to final customers – with resources coming from one of its other activities that are not. The introduction of unbundling, especially in its more radical form, represents a structural remedy that removes not only the possibility but eventually also the primary interest of the firm controlling the network in discriminating other market players. The removal of such interest has another important – yet often overseen – advantage that other non-structural measures aiming at establishing a level playing field not always present: it facilitates regulatory oversight.

However, the application of unbundling rules also presents a downside: it may reduce or eliminate some of the economies of scope previously available to the vertically integrated firm. Therefore, the implementation of unbundling calls for the development of new coordination mechanisms within the restructured sector in order to limit resulting inefficiencies.

What types of unbundling do exist?

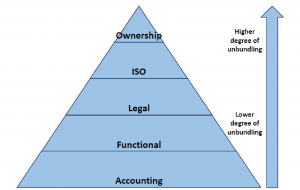

Different degrees of unbundling are possible with different levels of effectiveness.

- The first and most basic one is account unbundling. In this case, the firm is obliged to separate the bookkeeping of its various activities, highlighting the costs and revenues that derive from each of them. The information made available increases transparency and allows the regulatory authority to better assess the adequacy of the tariffs proposed for the regulated activities and to detect possible instances of cross-subsidisation.

- Functional unbundling is the subsequent step. In this case, the firm is obliged to re-organise its internal structure and attribute responsibility for its network and competitive activities to different units that can take decisions independently one from the other. The introduction of a “Chinese wall” between those units can be part of the obligations foreseen by this type of unbundling.

- Legal unbundling can be introduced in order to further prevent the implementation of discriminatory practices. In this case, a separate legal entity is established and tasked with network activities. Due to this higher degree of separation, its management is supposed to operate more independently. However, the legally unbundled entity may still be owned by the previously vertically integrated firm through a holding company. As a result, an interest in discriminating other market players and favouring the parent firm cannot be totally excluded.

- A possible way out is represented by the establishment of an independent system operator, not owned by the vertically integrated firm, that is tasked with the operation of the existing infrastructure and the planning of its expansion, while the ownership of network assets can remain in the hands of the integrated firm. This model has its merits in promoting the efficient use of the existing infrastructure; however, it is not devoid of drawbacks and has been rarely used in Europe.

- The ultimate form of unbundling is ownership unbundling. In this case, a firm owning and operating a network cannot be active in any competitive segment of the supply chain nor have an interest in any company involved in those activities. The opposite is also true: an electricity generator or a gas supplier cannot have any stake in the fully unbundled network company. This extreme form of separation reasonably solves the issue of discriminatory access to the network.

The figure below summarises the different degrees of unbundling.

What are the rules on unbundling in the EU?

In the EU, rules on unbundling changed over time and became gradually stricter, in particular as far as transmission is concerned. The Third Energy Package adopted in 2009 foresees ownership unbundling as a default option for electricity and gas transmission, while for electricity and gas distribution legal unbundling is required. Distribution system operators (DSO) with less than 100,000 customers are exempted from this requirement: account and functional unbundling are considered sufficient in this case. In 2019, the recast of the Electricity Directive contained in the Clean Energy Package does not significantly change the legal framework but provides some additional specifications on the possibility for system operators to own, develop, manage or operate storage facilities and recharging points of electric vehicles. It also provides that electricity DSOs involved in data management have to adopt specific measures to exclude discriminatory access to customer data from eligible parties and that vertically integrated firms do not get privileged access for the conduct of their supply activities.

If you still have questions or doubt about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Relevant resources and links

- A discussion of several topics related to the regulation of electricity networks in Europe, including unbundling, could be found in a book edited by Leonardo Meeus and Jean-Michel Glachant in 2018: “Electricity Network Regulation in the EU”.

- An analysis of the case of electricity DSOs and the new challenges posed by the recent developments in distribution grids (penetration of distributed generation, management of local congestion, etc.) can be found in a report on the Clean Energy Package published by Florence School of Regulation in 2019.

- An interpretative note on the unbundling regime present in the Third Energy Package can be found in a document published by the European Commission in 2010.

- Finally, an assessment of the current implementation of the rules on unbundling in the EU, including a description of the changes occurred with the adoption of the Clean Energy Package, can be found in the Status Review published by the Council of European Energy Regulators in 2019.

- FSR Annual Training on the Regulation of Energy Utilities discusses the importance of unbundling in the energy sector.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights