The TEN-E Regulation

What is the Trans-European Networks for Energy (TEN-E)? Which policy aspects do the chapters of this regulation address? And what is the role of TEN – E in the European Green Deal?

The Trans-European Networks – Energy (TEN-E) Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 347/2013) aims at fostering the development of cross-border energy infrastructure in Europe. The following statement from the TEN-E regulation text defines clearly its functions and objectives.

“This regulation lays down rules for the timely development and interoperability of trans-European energy networks in order to achieve the energy policy objectives of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) to ensure the functioning of the internal energy market and security of supply in the Union, to promote energy efficiency and energy saving and the development of new and renewable forms of energy, and to promote the interconnection of energy networks. By pursuing these objectives, this regulation contributes to smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and brings benefits to the entire Union in terms of competitiveness and economic, social and territorial cohesion.”

In other words, the TEN-E Regulation addresses the ‘’hardware’’ of the internal European energy market. Network codes for electricity and gas address market, system operation and grid connection rules, the ‘’software’’ of the EU internal energy market.

What is in the TEN-E regulation?

The TEN-E regulation has six chapters. A first chapter containing the general provisions, i.e. subject matter and scope and the definitions. Then four core chapters:

- Chapter II: Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) – the identification of PCIs

- Chapter III: Permit granting and public participation – the implementation of PCIs

- Chapter IV: Regulatory treatment – Rules and guidance for the Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA), Cross-Border Cost Allocation (CBCA) and incentives for PCIs

- Chapter V: Financing – Determining PCI eligibility conditions for PCIs to avail EU financial assistance via the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) for Energy

The last chapter covers final provisions such as those on reporting, evaluation and transparency. Some of the key aspects of each of the four core chapters are summarised below. Note that this article does not exhaustively cover all articles of the Regulation. Instead, the goal is give the reader a general understanding of what the TEN-E Regulation is about.

Chapter II: Projects of Common Interest

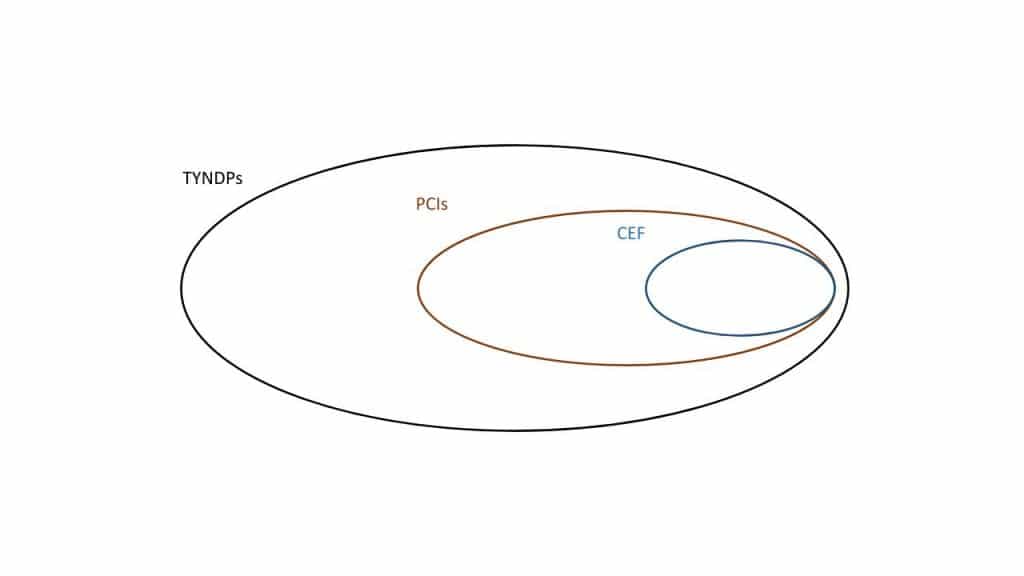

An important concept in the TEN-E regulation is that of a Project of Common Interest (PCI). PCIs are infrastructure projects with a pan-European impact as essential for completing the internal energy market. The first list of PCIs was published in 2013. The list is updated every two years and contains a selection of transmission projects, smart grids and storage projects for both electricity and gas and carbon dioxide transport infrastructure.

This chapter of the TEN-E regulation covers the definition, selection, implementation and monitoring PCIs. Article 3 provides guidelines on developing a Union list of PCIs based on a regional list. The regional list will consist of projects selected by 12 regional groups consisting of EU member states. Article 4 provides criteria for what constitutes a PCI, while article 5 concerns steps for implementation and monitoring. Finally, article 6 articulates functions of a European Coordinator. According to this article “ Where a project of common interest encounters significant implementation difficulties, the Commission may designate, in agreement with the Member States concerned, a European coordinator for a period of up to one year renewable twice.”

Chapter III: Permit granting and public participation

One of the advantage of being nominated as a PCI is that selected projects may benefit from accelerated planning and permit granting, a single national authority for obtaining permits, lower administrative costs due to streamlined environmental assessment processes, increased public participation via consultations, and increased visibility to investors.

This chapter details on how the TEN-E Regulation ensures a fast and seamless permit granting process for PCIs. PCIs are accorded a ‘priority status’ at the national level (Article 7). A one-stop-shop approach for permit granting is also mandated. According to Article 8: “each Member State shall designate one national competent authority which shall be responsible for facilitating and coordinating the permit granting process for projects of common interest.” Article 9 lays down transparency and public participation criteria. Finally, article 10 treats the duration and implementation of the permit granting process. More information about raising public awareness for infrastructure projects can be found here.

Chapter IV: Regulatory treatment

An important part of the TEN-E regulation is the methodology for a system-wide cost-benefit analysis (CBA), the rules and guidance for the cross-border cost allocation (CBCA) and risk-related incentives for a PCI.

First, Article 11 mandates the European Network of Transmission System Operators (ENTSO) to develop a system-wide cost-benefit analysis (CBA) methodology. The CBA methodology needs to be applied to create the subsequent Ten-Year Network development Plans (TYNDPs). Being part of the TYNDP is requirement for transmission projects to be eligible for the PCI status. Additionally, the project promoters need to conduct a CBA to demonstrate that it brings a net increase in pan-European welfare. More information about the CBA methodology can be found here and here (offshore electricity infrastructure).

Second, Article 12 covers Cross-Border Cost Allocation (CBCA). In short, countries used to agree on cross-border investments on the assumption that they would each pay for assets in their territories. If they both benefitted enough to justify these costs, they would agree to go forward with the investment. The problem was that when one of them had doubts, the project would be cancelled or delayed. With the CBCA process, the TEN-E Regulation mandated the European Union Agency for Energy Regulators (ACER) to act as a mediator in these kinds of cases. Project promoters make a CBCA proposal for PCIs, and if the National Energy Regulators (NRAs) cannot agree ACER can intervene. More information about the CBCA process for PCIs can be found here. Experiences with CBCA decisions are described here.

Third, Article 13 mandates Member States to provide some dedicated investment incentives. In many countries, risk/remuneration profiles are set according to the general regulatory regimes. Typically, these risk/remuneration profiles are the same for different projects within a country. An issue is that some specific strategically important or necessary investments can be more risky than other more conventional projects. The idea behind dedicated investment incentives in the TEN-E Regulation is that where a project promoter incurs higher risks for the development, construction, operation or maintenance of a PCI, compared to the risks normally incurred by a comparable infrastructure project, Member States and NRAs shall ensure that appropriate incentives are granted to that project. More information about dedicated investment incentives can be found here and here (offshore infrastructure).

Chapter V: Financing

PCIs can access financial support. A total of €5.35 billion from the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) is allocated for the period from 2014-2020 for this purpose. Article 14 of this chapter covers the criteria eligibility of PCIs for financial assistance. More information about the award criteria for CEF funding for PCIs can be found here.

Importantly, ACER issued a Recommendation stating that a CBCA for which the default cost allocation clearly results in a net loser, i.e. a country that benefits less than the costs it is expected to incur by investing in the assets in its territory, is not a justification for applying for CEF-funding. Instead, the other beneficiaries should be first asked to compensate the net loser for its loss, and other beneficiaries can even be third countries that do not host any of the assets in their territory but clearly benefit from the project.

As illustrated in the figure below, only a subset of PCIs, which are in itself a subset of the projects taken up in the TYNDPs (for gas and electricity), can benefit from CEF funding.

TEN – E and European Green Deal

The European Green Deal calls for a review of the TEN-Regulation. More precisely, in its communication the European Commission states “The transition to climate neutrality also requires smart infrastructure. Increased cross-border and regional cooperation will help achieve the benefits of the clean energy transition at affordable prices. The regulatory framework for energy infrastructure, including the TEN-E regulation, will need to be reviewed to ensure consistency with the climate neutrality objective. This framework should foster the deployment of innovative technologies and infrastructure, such as smart grids, hydrogen networks or carbon capture, storage and utilisation, energy storage, also enabling sector integration. Some existing infrastructure and assets will require upgrading to remain fit for purpose and climate resilient.”

If you still have questions or doubt about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Relevant links

Revision of the TEN-E regulation: an academic perspective

Courses