The Swedish Experience with Dynamic Retail Tariffs

This is the third instalment of our November Topic of the Month with FSR Global: Unravelling the nuances of Dynamic Tariffs for electricity retail

November Topic of the Month: Unravelling the nuances of Dynamic Tariffs for electricity retail

Instalment 1: Implementing Dynamic Tariffs for Electricity Retail: Choices and Barriers

Instalment 2: The Spanish experience with dynamic tariffs

Instalment 3: The Swedish Experience with Dynamic Retail Tariffs

Instalment 4: Time of Use and Dynamic Pricing Rates in the US

The Swedish Experience with Dynamic Retail Tariffs

by Therese Hindman Persson, PhD, Chief Economist, the Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate

This note presents a brief overview of the Swedish experience with dynamic retail tariffs and gives some food for thought going forward. In Sweden, the retail market for electricity has been subject to competition since the market was deregulated in 1996. For consumers, this means they can buy their electricity from any electricity supplier (retailer) of their choice. The electricity is then delivered or distributed by a distribution system operator (DSO). The retailers compete on the market and the pricing is free while the DSO is a regulated monopoly. Today Sweden has roughly 129 active retailers who serve their customers with electricity which they buy on a power exchange or via bilateral agreements with producers.

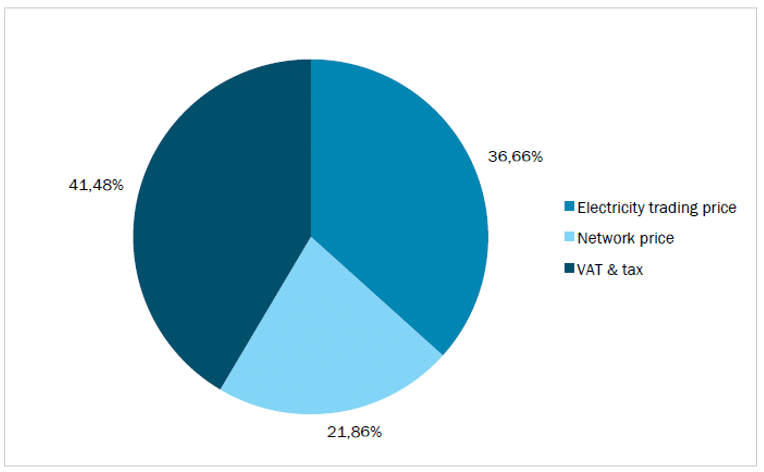

Price signals and electricity consumers

Consumers pay a total price for electricity that is typically divided into three components: energy, network and taxes & levies. The energy component comprises wholesale energy costs and the supplier’s margin (together referred to as electricity trading price) where 85-90 per cent of the total represents the cost incurred by the electricity supplier to purchase the electricity needed. While the network component is made up of various transmission and distribution-related costs, taxes & levies can be considered policy charges. In Sweden, a typical household consumer faces a total cost of electricity that is divided between these three components in roughly the percentages presented below. In addition, most consumers receive two invoices, one related to the energy component and one related to the network component.

The deregulation of the Swedish electricity market opened for more innovative and more dynamic pricing options than before thus making it more attractive for a consumer to be active on the market. Dynamic pricing of electricity means that at least part of the price that consumers pay for electricity varies over time. It could be the electricity trading price, the distribution tariffs, or both. If both the energy and network components are priced dynamically then some consumers may face more than one price signal at a time. These signals could be reinforcing one another but they could also move in opposite directions and becoming from different actors. In Sweden, most of the dynamic comes from the energy component even though there are cases of dynamic network tariffs too. In Sweden, most consumer contracts (energy component) are either fixed or variable. The variable price contracts are calculated based on the spot price adjusted for customer power takeoff profiles, while fixed-price contracts are based on futures prices adjusted for customer power takeoff profiles. Prices to consumers in the various bidding zones (Sweden has four bidding zones) follow the spot prices in each bidding zone. However, there is ongoing work at the Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate on developing regulations regarding network tariff design in order to enable the network component to become more dynamic too.

Dynamic pricing is important

Benefits of dynamic pricing include enabling consumers to be more active in the market. Dynamic pricing stimulates competition among electricity suppliers, and it makes it possible for consumers to adjust consumption patterns in response to price signals thereby lowering overall electricity costs. This lower cost would then stem from both consumption shifting to avoid peak price hours but also lower margins on contracts based on spot-related prices if the market is sufficiently competitive.

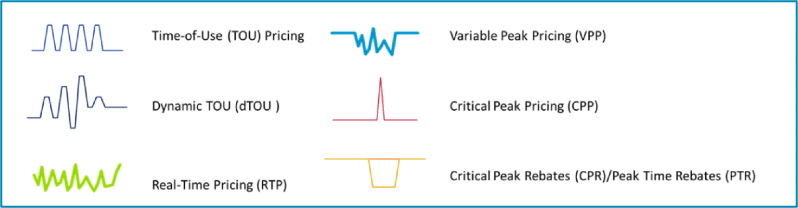

There are many different pricing models for dynamic pricing where real-time pricing (RTP) involves the most frequent price fluctuations. Other options include Time-Of-Use (TOU) tariffs, dynamic TOU tariffs, variable peak pricing, critical peak pricing, and critical peak or peak-time rebates, see below for a simplified graphical illustration. The main difference between various pricing models is how frequently the price varies and how the price variations are communicated.

However, when it comes to definitions, Article 2 (15) of the recast Electricity Market Directive defines a dynamic electricity price contract as :

“An electricity supply contract between a supplier and a final customer that reflects the price variation at the spot markets including day-ahead and intraday markets, at intervals at least equal to the market settlement frequency.”

Based on this definition, the Council of European Energy Regulators (CEER) recommends that dynamic price contracts should refer to the day-ahead market prices for the sake of simplicity. Contracts can also make use of wholesale prices on the intraday market, although such tariffs will be more complex to implement.

Regulator’s role

In Sweden both the wholesale and retail markets are competitive, and the country also benefits from early roll-out of smart meters and reliable communication networks. These are all important features for dynamic pricing, especially RTP, to work well. However, there are important lessons learned and improvements to be made based on the Swedish experience some of which are mentioned below.

- In Sweden, there has been a strong focus on digitalization and roll-out of smart metering systems since the beginning of 2000. Already in May 2010, 91 per cent of the meters could register hourly values remotely and in 2017, a new amendment was made to the legislation so that all electricity consumers can request hourly metering without extra cost. Installing the meter is a DSO responsibility.

- In Sweden, we have a supplier of last resort system. When a consumer does not make an active choice of electricity supplier, the DSO assigns a supplier to the consumer. However, this means that the contract the consumer gets may not be the most favourable for the consumer. In fact, on average, the price of such designated contracts is 20–30 per cent higher than for other types of contracts. Information from the Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate suggests that consumers living in apartments are relatively more likely to be inactive than other consumers.

- The most dynamic part of the electricity cost (i.e. the electricity trading price) is only a fraction of the total cost of electricity and hence the price signal is not as clear or strong as it could be. If the aim is to stimulate consumer activity it is critical that the price signal is sufficiently strong and that it reaches the consumers. There is also recent research indicating that there are benefits from coupling the price signal with information and communication activities as well as technological options like automation in order to affect behaviour.

- The dynamic pricing that we have is good but only a step in the right direction as long as the total cost of electricity for the consumer is close to 60 per cent fixed. This percentage includes both taxes & levies and the network component that in most cases is fixed.

- Sometimes it is argued that dynamic pricing can cause problems for vulnerable consumers. However, in Sweden vulnerability in terms of, for example, low paying ability is handled through the social security system and not through electricity prices as this is more efficient and will contribute to lower the overall cost for the consumers.

Towards a sustainable electricity future

From time to time arguments on limiting consumer choice are put forward on the grounds that dynamic pricing is difficult for consumers to manage and that there are risks that consumers will be exploited. This is odd. Consumers are indeed very good at managing goods and services with dynamic pricing and we believe they can handle electricity too. Dynamic pricing models underly many consumer goods that are handled often for example groceries and clothes (both domestic and imported). In addition, many consumers including households save money in mutual funds, stocks and bonds that are known to have quite complex dynamic pricing.

We see active and involved consumers as key to well-functioning markets and a sustainable electricity system and therefore limiting choice per se is not considered the best way forward. We should not underestimate consumer ability but contribute to strengthening their abilities when needed. We do see there are challenges to be overcome and that there is a clear need for regulators to take steps to assist consumers. For example, regulators should monitor the behaviour of electricity suppliers to make sure customers are not exploited. The Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate has undertaken and continues to undertake information related actions towards consumers. In addition, we undertake several activities aimed at assisting consumers to be more aware of their rights, possibilities and responsibilities. We provide information to consumers on matters such as:

- How to change electricity supplier

- The costs of connecting to the electricity network. The time it should maximum take to have your meter replaced if needed in order to take advantage of hourly contracts.

- How to report your electricity supplier or DSO

- What to do if you experience a power failure

- Telephone support for consumers

- The Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate publish regular reports on market developments and a special report on customer complaints

- Independent price comparison tools are important. In Sweden, electricity suppliers that offer electricity contracts to electricity consumers are obliged to report the most common contract types to the price comparison website: elpriskollen.se Elpriskollen is run by the Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate and allows comparisons to be made between different electricity suppliers and their offers.

In Sweden, we consider demand-side flexibility (DSF) to be a cornerstone of an efficient future electricity system. For DSF to work well price signals are key and hence dynamic pricing of electricity, both energy and network is critically important going forward. As markets are characterized by e.g. asymmetric information the availability of independent and unbiased information to actors, especially consumers, in the market is vital. Regulators have a special and important role to play in balancing various interests and level the playing field in order to enable consumers and new actors to participate actively in the market should they wish to do so. The Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate is currently working on improving price signals coming from network tariffs. We have a mandate to issue regulations on network tariff design and the aim is to move towards even more cost-reflective tariffs that stimulate increasingly efficient use of the electricity network. Topics that are under analysis now include how to distribute residual costs, how to handle forward-looking costs and what do such costs include and what is the best way to provide locational signals that can have a real impact.

Interested in learning more about dynamic tariffs?

Read our policy brief: Dynamic retail electricity tariffs: choices and barriers