Stranded gas assets: the dilemma of the energy transition costs

Highlights from the online debate: The stranding of gas infrastructure assets

Stranded gas assets

Stranded assets are physical assets recorded on a corporate balance sheet whose investment value cannot be recouped and must be written off. In this debate, we discussed who should or could bear the costs of repurposing or retiring stranded gas assets. How do we identify those costs? How, if at all, should this process be reflected in tariff methodologies? Should transition costs be borne by the taxpayer? Stranding of gas assets is a means to an end but raises certain problems and, while there are many issues that already merit further investigation, the speakers and participants agreed that the current regulatory toolbox offers a number of solutions. Repurposing of existing assets may also be a solution, but here the regulatory tools are less well developed. How do we resolve the trade-off between fairness of allocation of the costs of the energy transition and how the costs are allocated efficiently in the eyes of different stakeholders? Many of the dilemmas of this transition have already been addressed in the broadband/telecommunications sector, including re-purposing issues.

Opening presentations

Ilaria Conti (FSR) set the scene. As part of the energy transition – which should lead us to an integrated energy system, the use of the energy infrastructure will surely change. We need to consider final energy demand and it is perhaps necessary to adopt a ‘no-regrets’ approach as a basis for future policy. We need to consider an evolving geography of consumption. In this context the hydrogen backbone proposal put forward by a number of EU TSOs is of interest. Almost 70% of this backbone network could be based on repurposed gas pipelines in identified clusters or valleys to meet foreseeable demand and then determining the most efficient way to meet it. But pipeline transportation is not always efficient and hydrogen demand is unpredictable. Nor is hydrogen as a transportation fuel always an efficient option. Repurposing LNG terminals should also consider how to meet demand efficiently. Infrastructure in the new valleys needs to be regulated appropriately. So, the key challenge is identifying which infrastructure can be repurposed and when. A European-wide approach – including the Ten-Year Development Plan is important. Stranding of gas assets may be unavoidable but limited. The solution to the issue requires a flexible and dynamic regulatory response to balance wider European principles against national interests.

Denis Hesseling (ACER) sketched out the basis of ACER’s regulatory focus. The consumer needs to be ensured of continuity of energy supply and should have a choice as to which fuel – heat, electricity or gas etc. – best suits their demand. It has proved difficult to remove existing consumers from the natural gas grid. One also needs to distinguish between TSO and DSO assets which are fully regulated so that the NRAs have the final say as to when and how gas assets should be stranded, whereas semi-regulated assets may be treated differently. Stranding is a political decision and raises fairness issues, especially if the stranded assets are to be financed by additional levies. But if the asset is repurposed and moved from one function to another, the value of the asset has to be preserved. Consumers should not have to pay twice. For stranding, the owner may prefer to keep the asset ‘alive’ as long as possible which may be contrary to the general interest if the remaining consumers must pay more.

How can all this be combined into a useful process? It could require devising realistic scenarios, with full stakeholder consultation and targeted regulatory supervision of how these scenarios will enfold. Getting the governance right is key. These scenarios must then be translated into models that could serve as an input for NRAs to determine which assets could and should be stranded or repurposed. Risks and rewards need to be carefully aligned especially in a cross-border context. One important regulatory tool is the treatment of depreciation, which offers different parameters to the NRAs – changing the deprecation profile for example, as the Dutch NRA has done. Detailed work on revising the regulatory asset based is unavoidable. Users must receive the right economic signals.

Takeaways from the panel discussion

The panel discussion was opened by Lisa Fischer (3EG) who also stressed that stranding was a means to an end. It is unavoidable that the demand for gas and therefore for gas infrastructure will shrink. Hydrogen infrastructure is likely to become a subsidiary to electricity infrastructure. Do we need the planned new expansions already in the system? We need to reap the benefits of system integration as this can drastically reduce costs of hydrogen roll out and make sure infrastructure planning is focused on where it is needed. Repurposing could lead to more stranding. Cross subsidization has to be avoided. Incentives for early retirement should be introduced where necessary. Who decides where the costs should fall? Are there new institutions such a climate panels that could take up that task?

Jan Ingwersen (ENTSOG) made the case for putting the question of how to ensure the most efficient transition of gas grids for the benefit of gas consumers, especially as gas demand is not likely to decline in the next 20 years. The scale of the regulatory challenges in relation to this transition is undeniable and it is not yet clear how fast electrification will evolve in the coming decades. Gas infrastructure may prove an invaluable backbone to ensure a smooth transition. Repurposing of existing infrastructure will be a major regulatory focus as this is key issue. Gas TSO have a responsibility to provide the right framework for transition and have to have the right incentives to do so.

Annegret Groebel (BNetzA/CEER) stressed the importance of ensuring competition and the role that this could play in dealing with the challenges of the transition. Minimising stranding is important, but assuming that repurposing of the majority of the infrastructure is the solution is too simplistic an assumption. Minimising costs is important, but so also is maximising the benefits by realising synergies afforded by system integration to reduce overall transaction costs. Existing regulatory tools can be put to good effect in finding the right combination as demonstrated by the CEER’s recent report on stranding of distribution assets. Accelerating depreciation on a degressive as opposed to a straight-line method can determine which users are paying what over time. The Dutch NRA also switched its WACC methodology to allow for a nominal rate. Risk premiums for new investment may also have to be re-assessed to ensure proper cost causation. These are the fundamentals of modern infrastructure regulation. Unbiased or neutral forecasting of demand is key to ensure we avoid the risk to replace one over-dimensioned network with another. This means developing and applying a uniform methodology in a whole system approach – to ensure that across Europe only efficient projects and not just infrastructure projects are assessed.

This theme was also echoed by Catherine Galano (Frontier Economics), who pointed out that there are already good examples of how the problem of declining demand can be addressed through ‘front loading’. Many solutions are already embedded in the mechanics of regulation. The UK has already reduced the lifetime over which gas assets can be depreciated in a regulatory decision in 2012. The Belgian regulator has mandated that all pipelines have to be depreciated by 2050 and Austria has taken a similar approach Varying WACC is also a useful lever for front-loading. Changing the depreciation profile is also an option, as demonstrated by the Dutch NRA considered how volumes to be consumed in the next regulatory period should impact on that profile. Targeted rules on exit from the RAB can also be used. Gas storage is a good example of how regulatory tariffs can reflect the exit of assets going forward and who pays over times.

The views of the audience

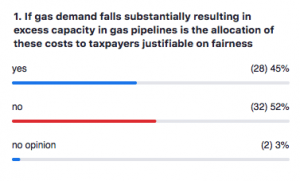

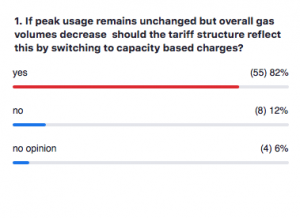

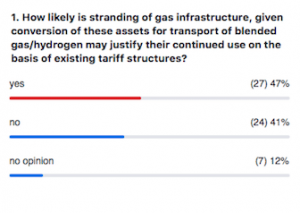

Participants were also asked to consider the results of the three polls.

In the first poll, participants were asked whether, as the decrease in gas demand will result in excess capacity in gas pipelines, the allocation of their costs to taxpayers could be justifiable on fairness grounds. A slight majority of participants thought that such an allocation could not be justified (52% of the respondents).

In the second poll, participants were asked whether, if peak usage remained unchanged but overall gas volumes decreased, the tariff structure would better reflect this by switching to capacity-based charges, a course of action supported by most participants (82% of the respondents).

The third poll asked to what extent the conversion of gas infrastructure assets to transport blended gas/hydrogen is likely to justify their continued use on the basis of existing tariff structures, thus avoiding their stranding. No majority of participants emerged on this issue, but more participants (47%) thought this possibility likely (against 41% of the participants considering it unlikely).

In conclusion, although there was broad consensus on how to streamline a number of regulatory instruments to deal with declining gas demand, the participants in this lively debate agreed that there is nothing in the regulatory toolbox on re-purposing – and this could be a major challenge going forward. A possible solution could be to develop a whole-system approach with a sophisticated CBA analysis.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights