Renewable Energy in the European Union

What is renewable energy? And which steps is the European Union taking to foster its penetration across the Member States?

What is renewable energy?

According to Directive (EU) 2018/2001, renewable energy refers to energy from renewable non-fossil sources, namely wind, solar (both solar thermal and solar photovoltaic) and geothermal energy, ambient energy, tide, wave and other ocean energy, hydropower, biomass, landfill gas, sewage treatment plant gas, and biogas (art. 21). It is important to note that renewable and non-greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting energy sources are not synonyms according to this definition. For example, nuclear power plants do not pollute the air or emit GHG when producing electricity, but the material most often used to generate nuclear energy, uranium, is generally a non-renewable resource and, as a consequence, nuclear energy is not considered renewable.

The (increasing) penetration of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) in an energy system is typically measured through metrics such as the RES share in primary energy demand or in the gross final consumption of energy. With respect to the power system, other metrics such as electricity production (in GWh) and installed capacity (in GW) are typically used.

Why does the EU care about renewable energy?

Several reasons justify the interest of the EU in the promotion of RES. Among them, there is the goal to achieve a more environmentally sustainable energy system, seen how RES contribute to the reduction of GHG emissions and local pollutants and, as a consequence, to climate change mitigation and improvement of air quality.

Furthermore, the penetration of RES in the energy mix can also help with other traditional goals of the EU energy policy, such as the competitiveness of energy prices and reducing imported fossil fuel reliance. Besides, the promotion of renewable energy can create new opportunities for local employment, help ensure the leadership of EU manufacturers in green technologies and contribute to overall economic growth.

EU commitment to renewable energy has been long established and is attested by art. 194 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which states that the Union policy on energy shall promote the development of new and renewable forms of energy, in a spirit of solidarity between the Member States. However, the same article specifies that the promotion of RES shall be without prejudice to the right of Member States to determine the conditions for exploiting their energy resources, their choices between different energy sources and the general structure of their energy supply.

How is renewable energy used per sector?

The use of RES has experienced rapid growth in recent years in the EU, driven by falling costs and policy support. Through appropriate technologies, RES can be used in different sectors, mainly electricity, transport, as well as heating and cooling. For the time being, RES penetration in the electricity sector has attracted most of the attention due to the availability of relatively more mature technologies like photovoltaics (PV) and onshore wind.

However, electricity currently represents only a fifth of the European final energy consumption. The transport sector, and the heating and cooling sector represent a relatively larger part of the final energy consumption, being about 30% and 40% respectively. As a result, they cannot be ignored if one aims to achieve significant decarbonisation of the energy system. Even so, efforts to increase the use of RES in these sectors have obtained limited results so far.

RES in the electricity sector

In the electricity sector, RES are used to produce electricity with negligible or null direct GHG emissions. The most relevant sources are in this regard bioenergy, hydro, solar and wind energy.

Their penetration in the electricity system depends on several factors, such as the availability of the primary natural resources, their cost-effectiveness vis-à-vis other energy sources, and the presence of other environmental and power system constraints. Hydropower and bioenergy are considered as flexible as their inputs (water and biomass) can be stored cost-effectively. On the contrary, wind and solar energy are known as Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) or non-dispatchable or intermittent renewables due to their intermittent availability that makes electricity generation not fully controllable.

RES in the transport sector

In the transport sector, the penetration of RES is driven by the switch to renewable transport fuels as well as by the uptake of electric mobility (electrification) – the latter is obviously conditional upon the electricity being generated by renewable sources. Renewable transport fuels can be biofuels, power-to-fuels (e.g. hydrogen and synthetic oils) or biogas. Biofuels are frequently divided into three categories or generations: first-generation biofuels are directly produced from food crops; second-generation biofuels are derived from a set of different feedstock and do not generally involve food crops; finally, third-generation biofuels – still at an early development stage – are obtained from algae and other such micro-organisms.

RES in the heating and cooling sector

In the heating and cooling sector, RES are used in various forms. Traditionally, biomass was utilised as fuel for heating spaces and water. More recently, heat pumps are installed to provide heating and cooling with the use of ambient or geothermal energy and electricity, possibly derived from RES too. However, most of the heating and cooling needs in the EU are still satisfied by the use of fossil fuels. Consequently, the European Commission has recognised the decarbonisation of the heating and cooling sector as a priority for the years to come. Further electrification, the development of highly efficient cogeneration and district heating, as well as the uptake of power-to-gas are considered among the main pathways to achieving decarbonisation of the sector.

What are the most relevant strategies and legislation to mainstream renewable energy in the EU?

The promotion of RES is a long term strategy of the EU, and several legislative initiatives have been taken over the years to foster it. Among them, the establishment of an Emission Trading Scheme (ETS), the adoption of targets to limit the GHG emissions from the sectors not covered by the ETS, the introduction of an electricity market design that better reflects the specificities of RES-based generation, the deployment of measures supporting energy efficiency, and the definition of long term Energy and Climate Plans at the national level.

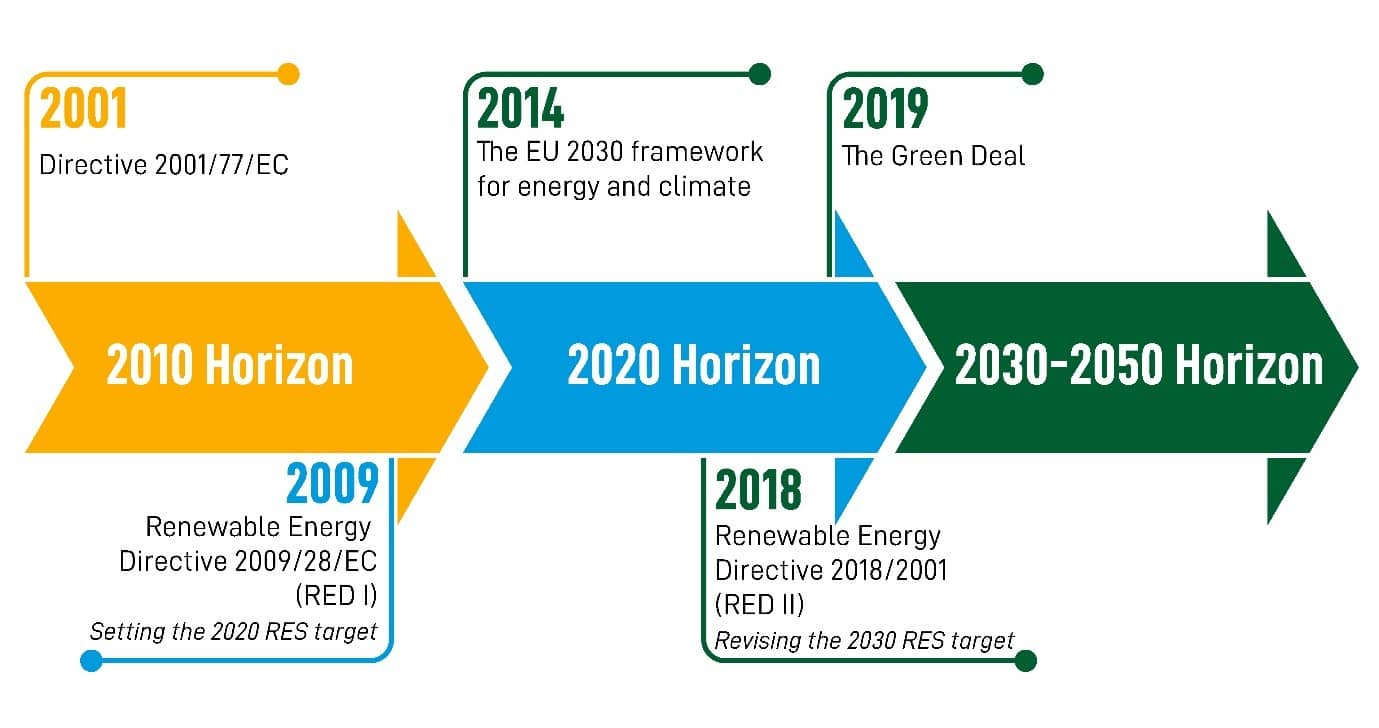

On top of these policies, the EU has adopted a series of specific measures and targets for the penetration of RES in the energy mix. These measures and targets, which reflect the conditions in the various countries and end-use sectors, have evolved over time and aim to provide clear signals to the Member States, investors, firms and energy consumers. They can be grouped according to the relevant time horizon they refer to: 2010, 2020, 2030 and 2050.

2010 horizon

After some early and limited attempts to promote “alternative energy sources” in the 1970s and 1980s, the EU started to elaborate a common policy on RES in the second half of the 1990s. The European Commission issued a White Paper for a Community Strategy and Action Plan in 1997, which was later followed by the adoption of Directive 2001/77/EC. The Directive established two targets for the use of RES in the energy sector: by 2010, 12% of gross domestic energy consumption had to be satisfied by RES; for electricity, the goal was set at 22,1%. Each Member State received an indicative target that combined with that of all the other Member States would have enabled the EU to reach the overall Community target. Although national targets were not binding, Member States were expected to provide detailed justification in case of failure to meet them. With the access of 10 new Member States in the Union in 2004, the 22.1% target set initially for electricity was reduced to 21%.

2020 horizon

The disappointment with the results of earlier policies, the increasing threat posed by climate change and the urgency to insure security of supply led to the adoption of the Renewable Energy Directive 2009/28/EC (RED I). Such Directive is part of the 2009 EU Climate and Energy Package, also known as the “2020 Package”, and sets the EU-wide target of RES share to 20% of gross final energy consumption by 2020. This target is then allocated to individual Member States by means of binding and differentiated national targets. The Directive also sets a 10% target for the total share of RES in the transport sector (this target is identical for all Member States).

In the heating and cooling sector, RED I does not include extensive requirements. These were later introduced by Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency, which provided specific measures aiming at increasing the efficient use of cogeneration and district heating. Beyond the setting of targets for 2020, RED I is important also because it defines a set of policies that Member States can or are required to implement to support the deployment of RES (e.g., direct support schemes, guarantees of origin, etc.). The Directive has also foreseen mechanisms to ensure cooperation between the Member States as well as third countries and facilitate the achievement of the national and European targets in a cost-effective manner.

2030 horizon

Discussions on strategies for the post-2020 era began soon after the 2009 Conference of the Parties (COP) 15 in Copenhagen in 2009.

More notably, in 2011, the European Commission published a roadmap to 2050 and later issued a green paper on an energy and climate framework for 2030. Building on the expected results of the 2020 Package, but at the same time departing from some of its elements, the European Council adopted a clear set of goals and policy choices in October 2014. In particular, it was agreed that the EU should cover with RES at least 27% of its final energy consumption by 2030. However, the possibility to define individual and binding targets for each Member States was explicitly ruled out.

The political decisions taken in October 2014 were later turned into legislative proposals and subjected to the ordinary legislative procedure. As part of the Clean Energy Package, the Renewable Energy Directive (EU) 2018/2001 (RED II), adopted after intense political negotiations, revised the 2030 climate and energy framework by moving the target for RES in 2030 upwards: 32% of final energy consumption instead of the initial 27%. The absence of national binding targets was confirmed, but the national RES targets for 2020 should constitute the minimum contribution of each Member State for 2030. On top of that, Member States are obliged to define integrated national energy and climate plans (NECPs), where they explain in detail how they plan to contribute to the common European targets and what measures they expect to put in place.

RED II updates the provisions related to the cooperation mechanisms available to the Member States and extends the EU sustainability criteria to cover also solid and gaseous biomass. Further, it sets a 14% minimum target of renewable energy in the final energy consumption in the transport sector by 2030. Each Member State is to pass this obligation to fuel suppliers. In this regard, the Directive encourages the use of advanced biofuels and biogas by limiting the amounts of first-generation biofuels that can be counted towards the target.

For the heating and cooling sector, each Member State is mandated to increase the RES share by an indicative 1.3% as an annual average calculated for the periods 2021-2025 and 2026-2030. The starting point is the RES share in the heating and cooling sector recorded in 2020. RED II also includes provisions for increasing the efficiency of district heating and cooling. More precisely, RED II requires the provision of consumers’ access to information on energy performance and the share of RES in their district heating and cooling systems. Furthermore, it allows consumers with non-efficient district heating and cooling systems to terminate or modify their contracts.

2030 to 2050 horizon

In late 2019, the European Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen announced a European Green Deal. Building on the vision expressed by her predecessor one year earlier, the deal consists of a set of legislative initiatives to further decarbonise the energy system and reach stronger climate objectives, including climate neutrality, by 2050. Among the initiatives foreseen, there is the proposal for a new European Climate Law and the revision of relevant EU legislation, as for instance the ETS Directive, the Effort Sharing Regulation, the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) Regulation, the Energy Efficiency Directive, the Renewable Energy Directive as well as the CO2 emissions performance standards for cars and vans.

In order to reach climate neutrality by 2050, the Commission proposed, in September 2020, to increase the target on GHG emissions and cut them by at least 55% by 2030. The pursuit of this target would naturally accelerate the clean energy transition and be consistent with a higher share of RES in the EU energy mix (the EC Impact Assessment accompanying the proposal refers to a 38.8% share). By June 2021, the Commission will come forward with proposals for the relevant policy instruments.

If you still have questions or doubt about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Athir Nouicer, Nicolò Rossetto.

Relevant links

· A presentation of the RED II and the novelties it contains vis-à-vis the RED I can be found in a technical report written by Athir Nouicer, Anne-Marie Kehoe, Jana Nysten, Dörte Fouquet, Leigh Hancher, and Leonardo Meeus: The Clean Energy Package (ed. 2020 edition) Technical Report, Florence School of Regulation, Energy, 2020.

· A discussion of what renewable gas is can be found in FSR Topic of the Month (from March 2018), written by Maria Olczak and Andris Piebalgs. More recently, a taxonomy for renewable gases is provided in a policy brief written by Ilaria Conti: How many shades of green? (March 2020).

· Data and statistics on the penetration of RES in the European energy mix can be found in the EU energy statistical pocketbook, published every year by the European Commission.

Courses

Regulation and Integration of Renewable Energy

Electric Vehicles: A power sector perspective

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights