Adequacy and Capacity Remuneration Mechanisms

This is the third installment of the Topic of the Month: Decarbonisation, infrastructure and electricity market design

The greater penetration of renewables-based generation in the electricity system poses challenges, related to their characteristics:

- Lower reliability of renewables-based generation (with respect to conventional generation: we know that the wind not always blows and, for sure, the sun does not shine at night);

- Greater variability of renewables-based generation (the wind might have steep changes in intensity, or clouds might come and go and obscure the sun);

- Lower predictability of renewables-based generation (the intensity of the wind or of the solar irradiation might be difficult to predict with the same accuracy as the generation of a conventional plant, especially several hours or days ahead of real time).

These characteristics mean that the system needs to keep “reliable” resources[1] in reserve, (part of) which should be capable of being activated and ramping up and down quickly, to balance the potentially unpredictable and fast changing residual demand (the demand in excess of renewables-based generation). The selection and activation of these resources should be managed through what are typically referred to as “flexibility markets”[2].

However, it is still unclear whether these markets, and, more generally, the short-term markets – including the day-ahead market, which is still the reference market, and the intra-day market, whose importance will increase with the need of renewables-based generators to adjust their market position closer to real time – would be able to offer sufficient and sufficiently stable revenues to (continue to) attract investments in the electricity sector.

The pattern of prices on these markets are going to change as a result of the greater penetration of renewables-based generation, most of which are characterised by zero or near-zero marginal/ incremental costs.

A simplistic assessment of the implications of this change suggests a larger number of hours in which the electricity price in the market will be zero or very low. However, in order for the generation capacity to recover its fixed costs, prices might reach very high levels, up to the value of lost load, in a few hours.

This trend is already emerging in Europe, where the frequency of both negative prices and price spikes[3] has increased by 170%[4] and 1/3[5], respectively, between 2016-2017 and 2019-2020, with more than 1,900 negative-price instances and 2,369 price spike instances recorded in 2020.

A more elaborate assessment could however recognise that the distribution of prices might not necessarily end up being as binomial as it first appears, as new resources will take advantage of extreme prices. Very low prices might promote electricity demand from storage facilities, which might then be able to sell electricity back when prices are high. Demand response will also be activated at times of very high prices. Therefore, low prices might end up not always being that low and high prices not always being that high.

Capacity remuneration mechanisms (CRMs) have been part of the electricity sector landscape for many years, and lately they have been advocated to preserve the viability of backup generation. New requirements for these mechanisms were introduced by the 2019 recast of the Electricity Regulation[6].

Here two schools of thought compete. On the one side, investors in the sector claims that CRMs will be more and more essential going forward, to provide investors with the stability in their revenue streams that a more binomial distribution of short-term electricity prices threatens. On the other camp, the European Commission among others, claims that a fully functioning short-term energy market, providing efficient investment signals, is the best means to ensure resource adequacy and security of electricity supply. In this respect, CRMs should be implemented only if a regional system adequacy assessment highlights adequacy concerns and to the extent and until such concerns are not addressed by measures to eliminate any identified regulatory distortions.

A composition of this debate might point to the fact that, while, in theory, markets can always clear (at the value of lost load in case of scarcity), this might happen at prices which are so high to be socially disruptive and politically unacceptable. To avoid or minimise the probability of the market clearing at such prices, CRMs might be implemented, not only as a transitory solution. However, in this context, it is imperative that CRMs do not distort the functioning of the short-term markets.

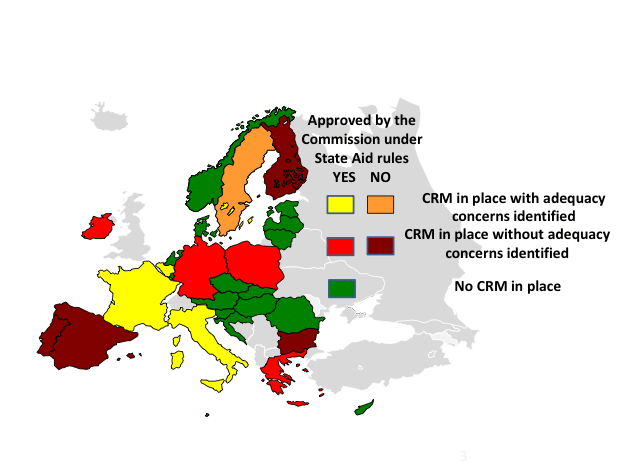

Anyway, as shown in Figure 1, CRMs are currently existing in twelve Member States and in seven of them they have been approved by the European Commission for compliance with State Aid rules. In several cases, CRMs are in place without any adequacy concern having been identified.

Figure 1 – Status of CRM in the EU (2020)[7]

Among the many CRMs which have been proposed or implemented, reliability options[8] could be considered the one which best complies with the design principles stated in EU legislation[9]. In fact, while a reliability option creates a strong incentive[10] for capacity providers to sell electricity on the market at times of high prices, it does not in itself create a direct obligation for capacity providers which have sold the option to do anything particular in the electricity market. In this sense, the reliability option minimises market distortions.

However, this conclusion rests on the strike price being set at a level that represents the ‘conceptual’ discriminant between market functioning, including under tight demand-supply conditions, and a situation in which nothing could prevent prices from increasing up to the value of lost load (or whichever other price cap is imposed on the market)[11].

So far, the European Commission and the EU legislator have not dared to propose or impose a standard design for CRMs, as it happened with the energy markets, but have limited themselves to expressing a “preference” for strategic reserve and setting some general requirements for CRMs.

[1] Years ago, reference here would have been made to generation capacity, but technological development and digitalisation promote the participation of demand in the market through “demand response”.

[2] This is not a formal definition of any market, but it is meant to comprise the balancing and some ancillary services markets. Read more

[3] ACER defines “price spikes” as hourly day-ahead prices which are three times above the theoretical variable cost of generating electricity with gas-fired power plants based on the TTF DA gas prices in the Netherlands.

[4] From 522 to 1,424, on an average annual basis. ACER/CEER Annual Report on the Results of Monitoring the Internal Electricity and Natural Gas Markets in 2020 – Electricity Wholesale Markets Volume, October 2021.

[5] From 1,620 to 2,154, on an average annual basis. The number of spike price hours in the European electricity market were atypically low in 2018 (240).

[6] Regulation (EU) 2019/943, articles 21 and 22.

[7] The relationship between CRMs and the identification of adequacy concerns relates to 2019. Source: ACER/CEER Annual Reports on the Results of Monitoring the Internal Electricity and Natural Gas Markets in 2019 and 2020 – Electricity Wholesale Markets Volume, October 2020 and October 2021.

[8] A reliability option is described, inter alia, in the Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the document Final Report of the Sector Inquiry on Capacity Mechanisms by the European Commission, COM(2016) 752 final, Section 5.4.2.1 as a scheme in which “the capacity provider will receive a regular payment […]. In return for this regular payment, the capacity provider that has sold a reliability option will be required to pay the difference between a market reference price and a strike price whenever the reference price goes above the strike price”.

[9] Article 22 of Regulation (EU) 2019/943.

[10] This is at least what reliability options are advocated for, including in the Commission Staff Working Document referred to in footnote 8. Note, however, that the differential payout for the capacity provider between selling and not selling electricity at times of high prices is the same in the presence of a reliability option as without it. For more detail on this point, see Alberto Pototschnig, Capacity Remuneration advancing the speed of Renewables, In my view, IEEE Power & Energy Magazine, January/February 2021.

[11] This was already recognised almost twenty years ago in the seminal work on the topic: the strike price of a reliability option could be considered “as a frontier between the normal energy prices (p<s) and the near-rationing or emergency prices (p>s)”. See C. Vázquez, M. Rivier and I. J. Pérez-Arriaga, A market approach to long-term security of supply, IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 17, No. 2, May 2002.

Read more

Capacity remuneration mechanisms in the EU

Moving the Electricity Transmission System Towards a Decarbonised and Integrated Europe

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights