A price cap on EU gas markets?

This is the first instalment of the Topic if the Month: Reforming energy markets

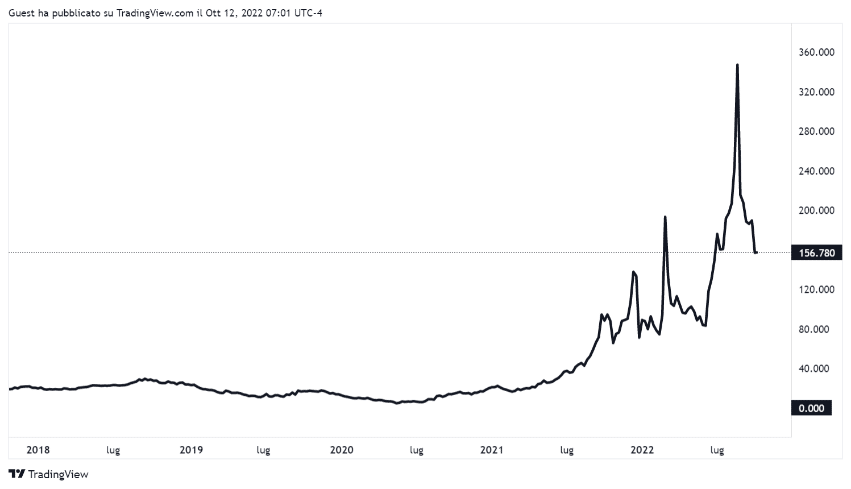

In the course of the last year and even more since the unprovoked and unlawful invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army, EU wholesale gas markets faced continuous instability, leading to extremely high price volatility and to gas prices spiking to unprecedented levels. The price of the month-ahead product traded at the main reference EU gas hub, TTF (Title Transfer Facility), touched 350 euros/MWh last summer, a shockingly high level considering that, in the 5-year to Spring 2021, TTF prices had hardly reached 30 euros/MWh (see Figure 1).

Skyrocketing gas prices, which also resulted in higher electricity prices, as gas is the marginal energy source for electricity generation in most markets in Europe, attracted political attention and the debate focused on the need to protect consumers, especially energy-intensive sectors and vulnerable and energy-poor customers.

Beyond the several measures adopted at the Member State level to cushion the impact of high energy prices on consumers[1], one of the most debated options in the recent energy debate has no doubt been the idea of imposing a cap on European gas prices. We contributed with several publications and other initiatives to the debate, particularly on regulatory interventions and potential reforms of the electricity and gas markets.

Already in May this year, the European Council invited the Commission to “explore also with our international partners ways to curb rising energy prices, including the feasibility of introducing temporary import price caps for gas when appropriate”[2]. The debate did not evolve significantly over the summer, until a recent letter[3] signed by energy ministers from 15 Member States called on the European Commission to introduce, as a priority, a price cap “applied to all wholesale natural gas transactions”.

The Florence School of Regulation has supported the EU institutions in their work to assess which measures could be adopted to mitigate the ongoing energy crisis. We contributed with several publications and other initiatives to the debate, particularly on regulatory interventions and potential reforms of the electricity and gas markets.

Specifically, on gas price caps, we recently published two Policy Briefs – Capping the European price of gas and Securing gas for Europe – in which, leaving aside the political debate on whether or not an EU gas price cap should be introduced, we analyse how a price cap in EU gas wholesale markets, if agreed at the political level, could be designed.

Capping: handle with care

The gas market has become a global market, particularly due to the increasingly important role played by Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) in the last 10 years, and presumably even more for Europe in the upcoming years. Indeed, internal dynamics in a regional market of significant dimensions (i.e. Europe) inevitably have direct consequences on a global scale and are likely to impact other markets.

At a general level, if gas prices in Europe were capped, the first challenge would be to ensure that LNG cargoes heading to Europe would not be re-directed to other global markets (typically Asia) where gas prices are higher. So, while spot prices in Europe are indexed to the prices of European gas hubs, when introducing a price cap on EU gas markets, one should not disregard the global dimension of LNG.

On the other hand, albeit Russian supply is progressively being phased out, a significant amount of gas still is and will be delivered via pipelines to Europe. The so-called “pipeline gas” and “LNG”, although identical in physical terms, are characterised by different market fundamentals and therefore, particularly in the case of Europe, they can, if needed, be addressed separately from a regulatory point of view. In particular, there are limited opportunities for external exporters of pipeline gas to the EU to redirect that gas to other destinations or liquefy it and sell it as LNG on the global market.

Our proposal

Based on these assumptions, in our Policy Briefs, we outline a two-part mechanism, addressing the two European gas market segments – pipeline gas and LNG – separately.

For the first segment (pipeline gas), we propose the following:

- regulatory intervention on the price of gas in organised market places, by using their technical functionalities, such as the Interval Price Limits of the Intercontinental Exchange[4]; and/or

- to mandate TSOs to provide gas balancing services at a predefined price or price range, which would act as a driver for price convergence of the gas traded in the EU

In fact, these two measures might be adopted alongside each other, to increase the effectiveness of the proposed mechanism.

For the second segment (LNG), we propose the introduction of auctions for procuring, on the global LNG market, any volume of gas needed by the TSO to balance the system. These auctions could be run by the TSOs themselves or, more appropriately, by a Single Buyer entity along the lines of the proposed Joint Purchasing Platform[5] included in the Commission’s REPowerEU plan. Such an entity could organise auctions in which external LNG suppliers bid a price premium above the prevailing price of EU pipeline gas, to supply LNG to the EU. The Single Buyer entity would buy this gas at the prices, including the premia, resulting from the auctions and sell it to the TSOs, according to their needs, at the predefined price or within the predefined price range. The price premia paid by the Single Buyer entity would have to be recovered through regulation[6].

In practice, under our proposal, shippers and traders would likely need to re-focus their trading strategies, having as a reference the capped gas price (or range) at which they would be able to buy or sell any quantity of gas. If the proposed mechanism were introduced as part of a credible commitment of European institutions to tackle the current energy crisis and the resulting skyrocketing energy prices, the gas volumes to be provided by the TSOs through the balancing mechanism could remain quite limited.

However, this is a best-case scenario, and it might well be possible that capping the price of pipeline gas in the EU might lead external suppliers of pipeline gas somewhat to reduce the flows to Europe. This is where the international outreach and energy diplomacy advocated by the Commission[7] could play a role, by explaining the sense of the mechanism and the opportunities it still offers to external pipeline exporters to the EU.

Finally, since many long-term contracts for gas supply to Europe are indexed to the spot price in EU markets, if the measures outlined above were successful in curbing the price of gas in the spot market, they would also have beneficial effects on the price of gas imported through long-term contracts.

Conclusions

As indicated in our Policy Briefs, we are generally not in favour of price caps, but we are currently experiencing a war situation, which might require specific regulation or market interventions.

We very much agree with the 15 Member States that a potential gas cap “can be designed in such a way as to ensure the security of supply and the free flow of gas within Europe, while achieving our shared objective to reduce gas demand”. However, none of the possible measures currently being discussed at the EU level is without drawbacks, and all involve a degree of risk. The challenge is to find the measure which minimises these drawbacks and risks.

The strategy outlined in our Policy Briefs is based on the different characteristics of the two market segments from which the gas to meet EU demand is sourced – the pipeline gas and LNG – and on certain assumptions on the structure of the market and on the behaviour of gas shippers and other market participants. There are clearly many design elements which would need further to be detailed and verified, as well as challenges which would need to be addressed – and in our two Policy Briefs we attempt to clarify at least some of them.

Only if the strategy is credible – the kind of credibility that the President of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, was able to give to the ECB’s commitment to defend the euro with his “whatever it takes” speech[8] in London on 26 July 2012, it will be able to deliver a reduction in the overall cost of gas consumed in the EU. The question is: does the EU currently have the ability to express the same resolve?

Notes

[1] Listed already as early as in October 2021 in the Commission’s Tackling energy prices: a Toolbox for action and support. Available here.

[2] Conclusions of the special meeting of the European Council of 30 and 31 May 2022, point 27)(a), second bullet point, on page 8.

[3] The letter of the Ministers of Energy to EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson can be found here

[4] The IPL functionality, and similar devices used in other trading platforms, acts as a temporary circuit breaker on these platforms, to diminish the likelihood and extent of short-term price spikes or aberrant market moves. While it is designed to be in force throughout each trading day, the protection that these functionalities provide are likely to be triggered only in the case of extreme price moves over very short periods of time. The proposed mechanism would give a more continuous role to these functionalities.

[5] However, while the Joint Purchasing Mechanism is generally considered voluntary, the Single Buyer entity would be most effective if it were mandatory for the procurement of the balancing gas required by the TSOs.

[6] A detailed description of how the premium could be recovered via regulation is included in our second PB

[7] For example, in May the Commission set up an EU Energy Platform Task Force to secure alternative supplies.

[8] “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And, believe me, it will be enough”.