A first look at ‘Save gas for a safe winter’: The EU’s fast-tracked proposal for protecting against a disconnection from Russian gas

The Council Regulation is the latest in a string of legislative and strategic actions to combat the ongoing energy crisis in Europe following Russia's war in Ukraine. In this article, we explore how the proposal manifests itself in concrete measures in each scenario, while also giving some reflections and national perspectives.

On July 26, 2022, the European Commission presented its ‘Save gas for a safe winter’ Regulation to an extraordinary meeting of the European Council, outlining steps to avoid emergency energy curtailments in the event of further gas delivery disruptions from Russia. The Council passed a revised version of the Regulation with a qualified majority (QM) (opposed only by Hungary) following the streamlined legislative procedure facilitated under emergency provisions of Article 122(1) of the TFEU, bypassing the European Parliament and the veto right of Member States. The final version of the Regulation was published today, July 28, 2022.

What are the key elements and why now?

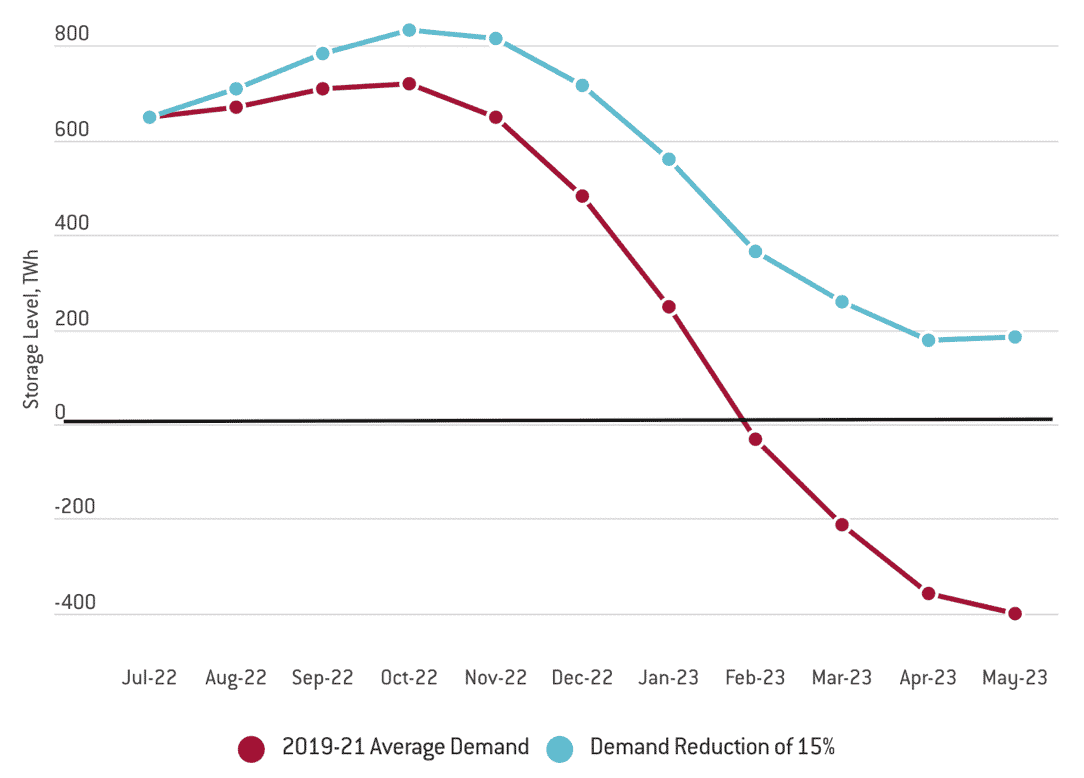

At average demand levels, the EU estimate that a full disconnection from Russian gas imports could result in a deficit of 30 billion cubic metres (BCM) of gas by March next year. The hope is that the measures proposed in the Regulation could save 45BCM, leaving a thin 15BCM buffer to protect against colder than average temperatures.

At the heart of the proposal is a 15% demand reduction target for the Member States between August 1, 2022, to March 31, 2023, compared to their previous five-year average consumption for the same period. This is initially voluntary and to be pursued by all Member States to their best efforts. However, in the event of an ‘EU Alert’ level event (details explained later) the target becomes mandatory, notwithstanding the following derogations.

According to Article 5 of the final version, there are derogations from the obligation for…

- countries that are not physically connected to the European gas grid, specifically island nations Ireland, Cyprus, and Malta. These countries are entirely exempt.

- In a similar vein, there is the possibility for partial derogations or adaptations to the target in cases where infrastructure does not allow for the provision of solidarity between the Member States. For example, the Iberian Peninsula, France, or Croatia. In these cases, Member States must still demonstrate that they are maximising their ability to provide solidarity with the infrastructure available (full details in Article 5(2e)).

- Member States may also be granted total derogations if their electricity grids are not synchronised with the European grid, and as such the reduction would risk disrupting electricity supply. This would likely apply for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. A partial/temporary derogation is also possible if electricity supplies are heavily reliant on gas-fired generation and as such are at risk of disruption from gas savings measures (full details in Article 5(2j)).

- Subject to individual assessment by the Commission, further partial derogations may also be granted where Member States have i) exceeded their gas storage filling targets (e.g. Czech Republic, Denmark, Poland), ii) if they are heavily dependent on gas as a feedstock for critical industries, or iii) if their gas consumption has increased 8%< in the past year compared to the previous five-year average (e.g. Bulgaria, Greece, Poland, Slovakia).

Notwithstanding the derogations outlined above, the 15% reduction is ubiquitous across the Union, regardless of the level exposure to Russian supplies at the national level. The sweeping nature of the measures are framed in a spirit of solidarity, considering the EU as one interdependent gas bloc, and building on the solidarity provisions already present in the Security of Gas Supply Regulation and confirmed by the European Court of Justice as a fundamental principle of EU law.[1]

Measures are voluntary at the point of adoption, and the Member States are free to deliver the reductions where most suitable in the national context. However, the target becomes enforceable in the event of an ‘Alert’ level event, the criteria, and circumstances of which we will cover shortly. As an exceptional measure, the Regulation will be valid initially for a 1-year period following adoption, to be reviewed in May 2023 for a possible extension.

The Council Regulation is the latest in a string of legislative and strategic actions to combat the ongoing energy crisis in Europe following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Whilst previous initiatives focused primarily on supply diversification options and storage, this most recent development focuses explicitly on avoided consumption. The approach is indicative of the fact that alternative supply options have now been more or less exhausted and in the event of a total disconnection from Russian gas, the only way to avoid energy shortages in the EU this winter is through actions on the demand side.

There remains hope that supplies from Russia will continue, following the resumption of flows through the Nordstream 1 pipeline to Germany, albeit only at 40% capacity initially, which has since dropped to 20%. Russian supplier Gazprom has shown it is willing to break long-term supply contracts, with six EU countries already having been totally cut off and 6 others receiving reduced supplies. Russia has earned more than triple its usual revenues from exports to the EU so far this year due to the exceptionally high prices, despite volumes falling by 300TWh, or roughly 22% of EU consumption. With this in mind, Gazprom and Russia are in a comfortable position to leverage Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, particularly considering EU leaders are repeatedly stating and strategising for an end to energy relations with Russia as soon as possible. There is a credible threat that Russia will completely shut-off of deliveries at some point during the coming months, and the EU should be prepared.

The ‘Save gas for a safe winter’ Regulation is a ‘prepare for the worst and hope for the best’ kind of approach, with the Commission favouring a managed and targeted curtailment of certain sectors, rather than an emergency shut-off. An unmitigated curtailment scenario could equate to as much as a 1.5% loss in GDP for the period in question, whereas a more proactive and managed approach could reduce this to 0.4%, according to the Commission’s modelling. IMF estimations suggest that potential GDP loss from a total cut off of Russian gas ranges from 0 – 6.5% of GDP depending on the Member State – with Hungary the most exposed. A 15% reduction in consumption would therefore focus initially on avoiding consumption where alternatives exist, including fuel switching to renewables, coal, and oil, as well as cutting demand in non-essential areas, such as in unoccupied public buildings or facilitating industrial consumers to auction off avoided consumption from their contracted capacity.

We will explore below how the proposal manifests itself in concrete measures in each scenario, and follow-up with some reflections and national perspectives.

Measures and what to expect

The following conditions can be expected at the corresponding level of urgency. Measures are broadly broken down according to the key actors/levels; i) EU, ii) Member States, iii) Gas Coordination Group.

Stage 1: pre-EU alert

These are the conditions that apply effective immediately upon adoption of the Regulation.

At the EU level:

- Best efforts to reduce gas demand by 15% in all Member States, notwithstanding total or partial derogations for… (full details in Article 5)

- countries that are not physically connected to the European gas grid, specifically island nations Ireland, Cyprus, and Malta. (total exemption)

- If electricity grids are not synchronised with the European grid, and as such the reduction would risk disrupting electricity supply. (total exemption)

- Member States have i) exceeded their gas storage filling targets, ii) they are heavily dependent on gas as a feedstock for critical industries, iii) their gas consumption has increased 8%< in the past year compared to the previous five-year average, iv) a high reliance on gas for electricity generation could jeopardise supply, or iv) infrastructure does not allow for the provision of solidarity between Member States. (partial and/or temporary exemption)

- Reinforce monitoring and mutual exchange of information, particularly to protect the Single Market.

- Strengthened governance and coordination mechanisms.

- Exploration of the possibility to host joint/regional auctions.

At Member State level:

- Acceleration of implementing measures providing alternatives to natural gas in all sectors, in particular towards clean energy sources.

- Voluntary auctions or tenders calling for offers to reduce consumption.

- Promote and if relevant activate interruptible contracts.

- Implement fuel switching measures for industry and electricity.

- Update of the national gas security of supply emergency plans and communicate them to the Gas Coordination Group by October 31, 2022.

- Limiting of heating and cooling temperatures in public buildings unless technically infeasible.

- Activation of other demand-side measures provided in the alert level in national gas security of supply emergency plans.

- Measures to reduce gas consumption by non-critical gas fire power plants.

Economic impact

No-regret options to be exploited, impact on public finances when compensation through auctioning of demand reduction needs to be granted, as well as for vulnerable households when needed. State intervention.

Role of the Gas Coordination Group

Reinforced monitoring, extended to industrial considerations, including of demand reduction, promotes the exchange of good practices setting the details of the measures.

Stage 2: EU alert

These conditions apply as per a Council-implementing decision, following a proposal from the Commission acting on the criteria of Article 4 of the Regulation. In this instance, a substantial risk of a severe gas shortage and therefore significant deterioration of gas supply in the Union is identified, and at least five Member States have declared an alert at the national level. The Commission will consult with relevant regional risk groups, the Council, and the Gas Coordination Group before declaring a Union-wide/regional ‘Alert’. The Council may amend the Commission decision by QMV.

At EU Level:

- Mandatory reduction of 15% of demand, notwithstanding the partial or total derogations outlined previously.

- Reinforce monitoring and mutual exchange of information, notably to protect the Single Market.

- Increase of the daily monitoring and information from the Member States to the Commission.

- If necessary, convene a crisis management group composed of crisis managers appointed by the Member States concerned.

At Member State level:

- Voluntary auctions or tenders calling for offers to reduce consumption.

- Update of the national gas security of supply emergency plans.

- Promote and if necessary activate interruptible contracts.

- Implement fuel switching for industry and electricity.

- Obligation for public buildings to limit heating and cooling temperatures unless technically infeasible.

- Activation of other demand-side measures provided in the alert level in national gas security of supply emergency plans.

- Measures to reduce gas consumption by non-critical gas fire power plants.

- Monitoring the impact of demand reduction on critical sectors across the EU, exchange of information between the Member States.

- The national gas security of supply emergency plans specify in more detail the measures planned by the Member State for each crisis level, such as releasing gas from strategic storage.

Economic impact

Support investments in alternatives to Russian gas, mitigate possible negative impacts in case of disruptions (including on employment and distributional impacts), likely need for state aid and EU to intervene by primarily but not exclusively market instruments.

Role of the Commission

Monitoring via the Gas Coordination Group, extended to industrial experts as appropriate of the necessary demand reductions for all Member States and per sector. Ensure solidarity approach and coordinate efforts as necessary.

Role of the Gas Coordination Group

Gas Coordination Group serves as a forum of information exchange on limitation, measures available and the impact of demand reduction on critical sectors, including industry, across borders to facilitate higher-level decision-making on demand reduction.

Reflections and implications

The measures proposed in the Communication and amended by the Council are a pragmatic reflection of the state of European gas availability, prescient of the fact that supply-side options are at their limit. Demand reduction has consistently been discussed in recent months but rarely focused on until now, it is clear that the Commission has made every effort to avoid the need to impose these kinds of measures. Independent analysis suggests that indeed the most effective course of action for the bloc on the demand side is to work in cooperation to mitigate the pain of supply shortfalls in the coming months. National governments and the Commission alike are under no illusion that this coming winter will likely be the first meaningful stress test for the security of supply provisions outlined in Member State emergency plans.

The Regulation is laudable in its aims to avoid the need for Member State emergency plans, and takes its lead from the Member States who have already been proactive in reducing demand to boost storage during the filling season, for example, the Netherlands, Croatia, and Denmark. Germany have also tabled a strategy at the national level to cut demand where possible. Nevertheless, it is easy to confuse reductions driven by a market response to high prices, for proactive policy choices. For example, in the Netherlands, a large share of gas consumption is from industrial and chemical sectors that have high sensitivity to energy costs, and therefore reduced consumption could be more of a reflection of un-competitiveness than deliberate gas stockpiling measures. If those conditions continue for too long then these industries are likely just to migrate to other regions with cheaper gas; this is not the aim of the Regulation.

It is nevertheless encouraging in principle to see the flexibility in provisions allowed for across the different circumstances of Member States in a way that reflects historical policy decisions and contemporary infrastructural limitations. This is a key development in the text from the original version that was arguably somewhat reductivist in its framing of solidarity. A more granular analysis suggests savings of between 0% and 54% could be necessary, depending on the Member State – a differentiated approach reflects that. Ultimately, the aim is to keep gas in the storages. The concern now shifts to whether the final overall savings will be sufficient, when considering the list of exemptions and the initial voluntary nature of the measures. Revised calculations based on the anticipated partial and total exemptions suggest that overall savings for the bloc could be closer to 10% rather than 15%, reducing further an already thin margin. The exemptions based on infrastructural limitations are clear but appeals to ad-hoc derogations on gas use in industry are more nuanced. Perhaps having reached a near-unanimous political agreement on solidarity is the most important component, establishing a precedent for more urgent solidarity in the event of total disruption, heading off the risk of a protectionist zero-sum game of non-cooperation.

There has been criticism around the discussion of actions for individual consumers and households. However, it should be contextualised. No government nor the Commission will attempt to impose direct measures on the length of showers or the temperature of houses. Household consumers are amongst the list of ‘protected customers’ defined in the Security of Supply Regulation and will therefore be amongst the last to be curtailed, this has always been clearly communicated. Measures taken now to avoid demand are specifically intended to avoid forced curtailment of vulnerable users, including households but also emergency and critical services. Furthermore, European citizens have shown strong humanitarian solidarity with Ukrainians during the war to this point; small sacrifices to limit heating and cooling can be an extension of that, with a scalable impact. Not to mention, lower energy consumption means lower energy bills.

From a legal perspective, the updated Security of Supply Regulation was introduced five years ago, but still only boasts six formal solidarity agreements between the Member States, where 10’s should exist. This is perhaps indicative of some apathy and complacency, but also speaks to the complexity of such arrangements. As regards enforcement, the EU is initially relying on the Competent Authorities of each Member State to oversee the reductions (Article 8) and leverages regular check-ins with the Council and Parliament to create accountability. It remains to be seen how effective this will be, but with near unanimous support in the Council for the initiative, there is cause for optimism.

The Florence School of Regulation congratulate the Commission and Council on their swift and considered cooperation to quickly deliver a final proposal on this complex and challenging issue.

Notes

[1] Judgment in Case C-848/19 P (Germany v Poland).