Why economic competitiveness is at the heart of the European project

This is the first installment of the Topic of the Month: Reflections on Draghi's report

Why economic competitiveness is at the heart of the European project

In Mario Draghi’s much-discussed competitiveness report, he concluded the foreword with the following: “Europe’s fundamental values are prosperity, equity, freedom, peace and democracy in a sustainable environment. The EU exists to ensure that Europeans can always benefit from these fundamental rights. If Europe can no longer provide them to its people – or has to trade off one against the other – it will have lost its reason for being.” In short, economic competitiveness is at the heart of the European social contract. Reviving European competitiveness means reviving public confidence in the ideals of the European project and providing an alternative vision for the future sufficiently compelling to resist growing pressure from radical populist alternatives.

1. A crisis of competitiveness

The need for a fresh look at European competitiveness can be attributed to many important and related events of the two decades. Perhaps the most prominent examples are the (i) Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and its impact on European security and energy markets, (ii) lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly regarding the fragility of international value chains, and (iii) the shift towards protectionism over globalisation in economic and trade policy, most notably the US-China trade war, and the recent re-election of Donal Trump. However, transcending all of these hugely important developments, is a simple economic reality underlying Draghi’s earlier message: Europe’s economy has never truly recovered from the financial crisis of 2008. With some exceptions in individual Member States, the EU has failed to deliver discernible improvements in quality of life to its population, and the immediate prospects are not very encouraging.

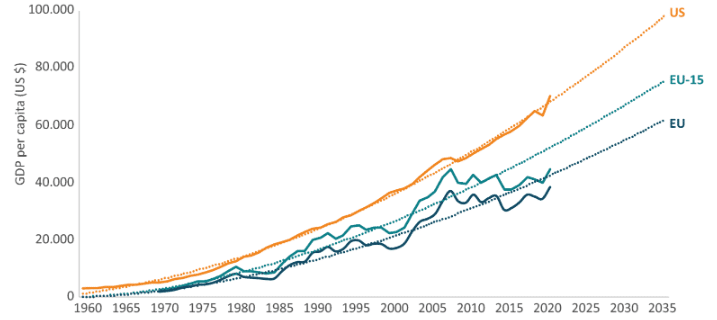

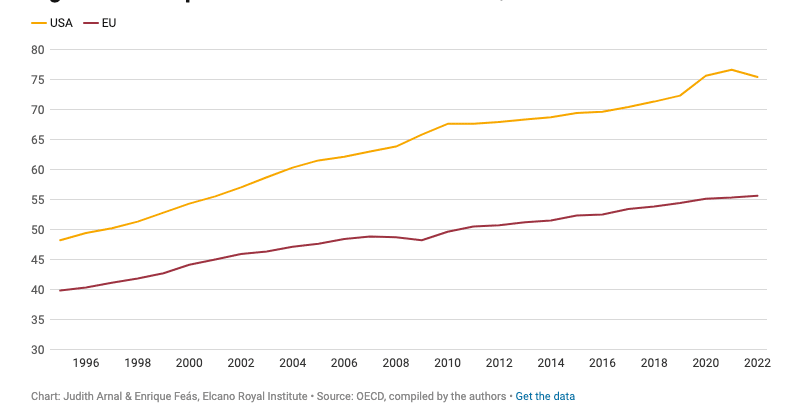

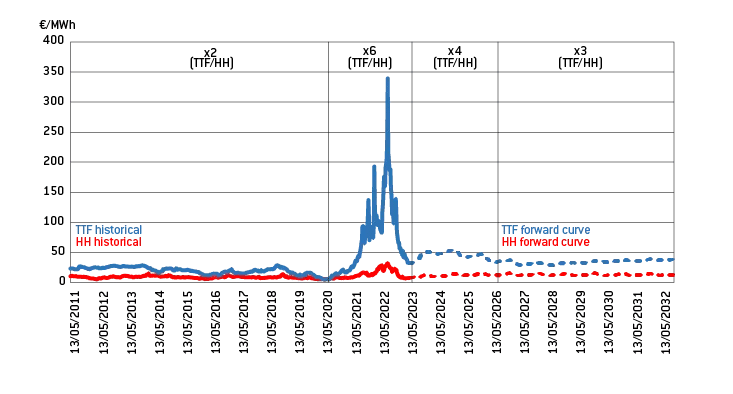

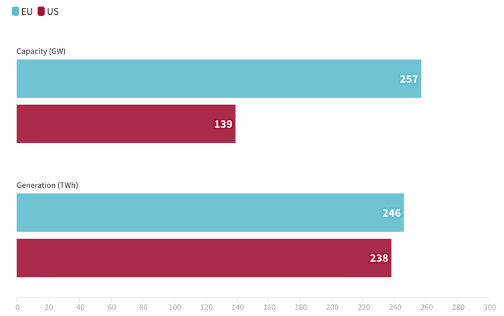

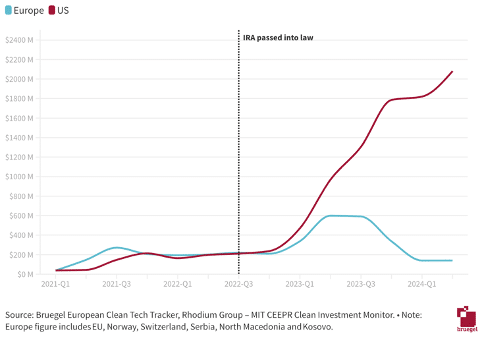

Draghi includes several different economic metrics to explain this economic stagnation in his report, below I have included five trends covering both incumbent economic activities and some of the new priority areas for advanced economies, namely clean energy production and clean energy technology manufacturing. The numbers compare the EU to the US, and they illustrate how Europe has long been falling behind the US in absolute GDP per capita (Figure 1) as well as productivity per hour worked (Figure 2), it illustrates that Europe’s energy prices are roughly triple that of the US, and 50% higher than they were before the energy crisis of 2021 – 2022 (Figure 3). Finally, the graphs outline that European solar is half as productive per installed unit relative to the US (Figure 4), and since the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed into law, investments in the US solar manufacturing industry have outpaced Europe by a factor of up to 10 (Figure 5).

2. What is the new vision for European competitiveness?

Reversing these trends arguably requires a new approach to policy design and implementation. Draghi’s vision, shared by President of the European Commission Ursula Von der Leyen[1], is a Europe that merges key policy objectives along common values and societal goals. In such a future, climate policy is no longer seen as an expensive luxury, but rather as an opportunity for economic modernisation and a pathway to sovereignty of critical services. International development and aid financing becomes less about the promotion of European norms and values and more about strategic mutually beneficial partnerships for economic gain.

This is a new way of thinking about policy, bridging conventional competencies and recognising cross-sectoral value (climate, energy, industry, health, foreign policy, …), but it is also not new at all. The European Green Deal of 2019 or the Horizon Europe research framework in 2020 also had this logic embedded into their designs. The novelty in the current debate is about the depth of transformation.

Put simply, it is one thing to earmark 37% of economic recovery funds to go towards net-zero aligned investments[2], or mandate that energy projects prove cross-border value to qualify for state aid[3], it would be another thing to centralise 100% of EU Emissions Trading Systems (ETS) revenues and redistribute them geo-agnostically… or to create a European Army.

In this article I will not re-explain the details of Draghi or Von der Leyen’s vision of European competitiveness, but I will offer a theoretical reference point for the logic and design of such an approach. I will also try to explain the current state of European competitiveness (good and bad), through the case study of clean hydrogen.

3. What does a renewal of European competitiveness mean for policy design?

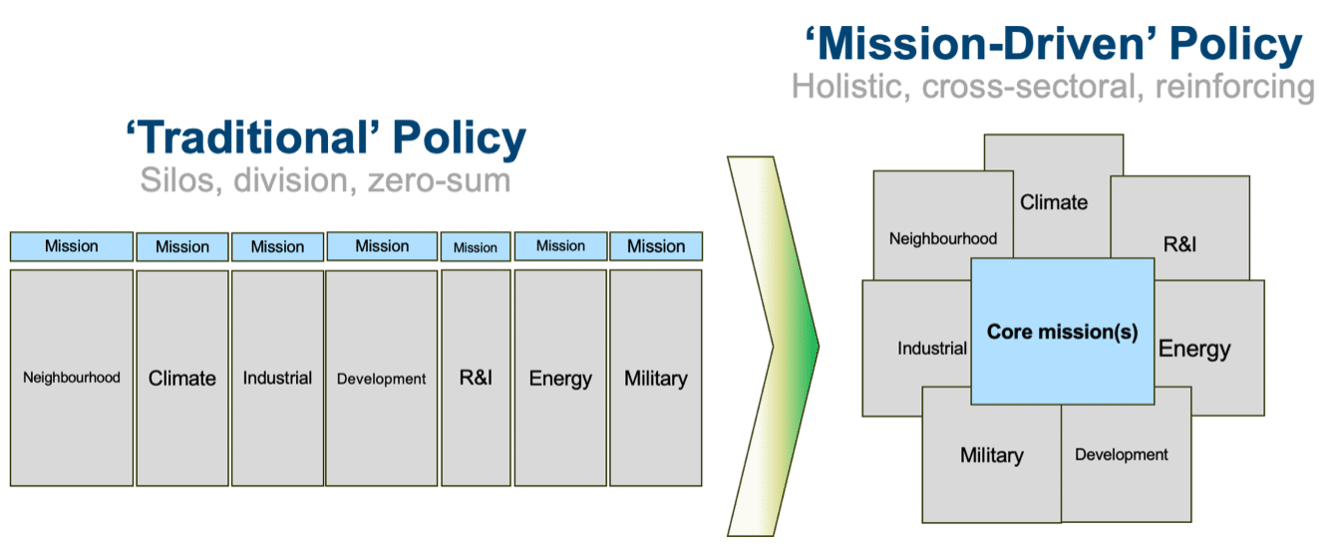

Some economists, like Draghi, but also other influential Italians like Mariana Mazzucato, have long argued that the ‘conventional’ way of doing policy in liberal democracies is too confined to ‘silos’, is too reactive, and lacks the tools to realise the possible co-values (and costs) related to policy interventions. Rather than taking as an assumption that the role of policy, and the public sector more widely, is to internalise market failures, we could begin with the assumption that policy is there to lead, to set agendas, and to create new markets. That society should agree on shared high-level goals, and that policies and projects should be guided by them, bridging conventional competencies and setting a direction of travel for the private sector to respond to.

In the case of clean hydrogen policy, yes, the entry point is decarbonisation, but the spillover effects touch energy security, energy prices, technology and innovation policy, employment and justice, air quality, development policy, heavy industry, circular economy, agriculture, and much more. Mazzucato might argue that conventional logic about allocating subsidies simply to the cheapest low-emission hydrogen technology can miss the potential spillover value (or costs) of a given technology relative to another. I will try to explain this with three of the most common clean hydrogen production pathways: low-carbon hydrogen produced by ‘reforming’ natural gas (blue), electrolytic hydrogen produced via electrolysis driven by electricity (green, yellow, pink), and methane pyrolysis (turquoise)[4].

In my view, low carbon hydrogen has close to zero spill-over added-value for the EU and implies some unnecessary costs (externalities). This is because it provides little to no new manufacturing, innovation or employment opportunities, whilst prolonging Europe’s dependence on expensive imported natural gas. This represents a technological pathway where it is structurally impossible that the EU can be competitive with the regions from which we purchase the natural gas, it is also a pathway where carbon and methane emissions are inevitable. Alternatively, electrolytic hydrogen means new technological value chains, balancing services for an energy system based on variable renewables, and potential improvements to energy sovereignty. However, it risks cannibalising scarce renewable energy resources, remains quite energy-inefficient versus other technological pathways, and potentially very expensive. For comparison, methane pyrolysis requires roughly 80% less electricity than electrolysis for the same quantity of hydrogen, as well as producing valuable ‘carbon black’ by-product that can be the basis for strategically important advanced materials, fertilisers, or inputs for manufacturing. The process is also emission negative when using biomethane as a feedstock, contributing to the EU’s carbon sequestration goals.

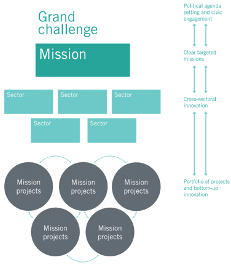

Briefly comparing these three production pathways highlights the potential variation in social ‘utility’ between them. This can be defined by contribution to policy goals outside of energy and decarbonisation (i.e. the primary policy function of clean hydrogen), relevant examples included here are carbon sequestration, circular economy, strategic raw materials, energy efficiency, methane emissions, strategic autonomy, manufacturing, and more. It is not to say that we should stop financing natural gas-based or electrolytic hydrogen and only finance methane pyrolysis. The pyrolysis pathway also risks increasing methane emissions, incentivising animal agriculture, and potentially has lower co-value in the manufacturing sector compared to electrolysis. The point is that by supporting technologies based on their contribution to a single policy goal (e.g. €/kg, €/MWh, or €/tCO2 avoided) might miss the very important wider societal costs or benefits of a given pathway. Figure 6 below tries to visualise how Mazzucato’s idea of ‘mission-driven’ policy can help to bridge conventional policy competencies and capture the cross-sectoral impacts of a single intervention. In this configuration, multiple sectors can be guided by the same ‘missions’ and ‘grand challenges’, and they should crowd in (and crowd out) certain technologies and behaviours with those horizontal agendas in mind.

Clean hydrogen for example would represent a ‘mission project’ contributing to ‘missions’ and ‘grand challenges’ set by the public sector. One project could demonstrate value to multiple sectors, missions, and grand challenges. For reference, Figure 7 tries to compare this approach to a more conventional, silo-specific, vertical model of missions contained within thematic policy domains.

In a ‘mission-driven’ configuration, the public sector is responsible for setting several high-level ambitions (cleaner air, strategic autonomy in energy services, creation of skilled jobs, etc). These must then translate into policies at the level of ministries and subsequently clearly signal a direction of travel to the private sector, with the expectation that it stimulates projects contributing to those aims. These feedback loops are expressed by the arrows in Figure 6.

4. Discussion: The good and bad of European competitiveness, explained through clean hydrogen

So far we have covered the fact that Europe is in a crisis of competitiveness and that one vision to transform our fortunes is to align the key policy agendas, perhaps most importantly climate, security, and industrial policy. Clean energy fits nicely within this framework as it is clean, secure (can be produced locally), cheap (in most cases[1]), and it provides opportunities for economic activity, specifically by reducing costs for energy intensive industry, as well as driving innovation and manufacturing sectors. By extension, clean hydrogen has many of the same characteristics, but it is a more nascent sector than renewable electricity generation, with greater scope for European technology leadership. Here I will outline some of the learnings from early experimentation within the sector, showing both cause for optimism and concern.

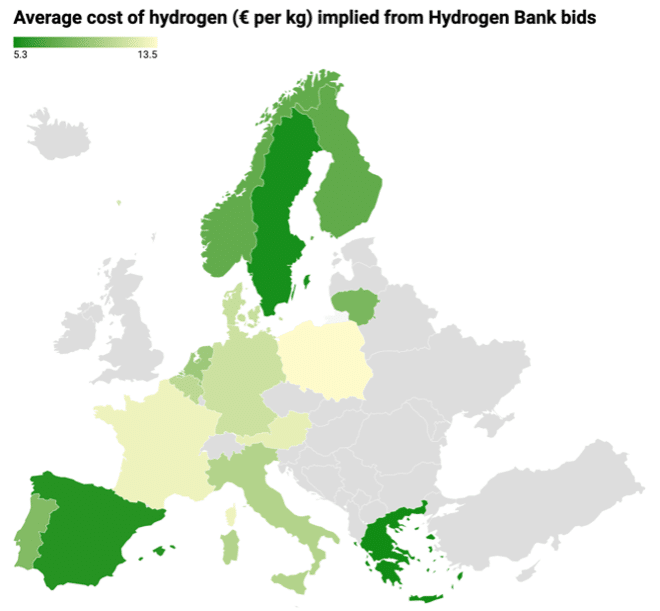

The European Hydrogen Bank (EHB) auctions[2] are a very useful reference point. This is a subsidy fund for renewable hydrogen production, financed by the EU budget via the Innovation Fund. The funds of the EHB are allocated ‘geo-agnostically’[3] via competitive bidding, which means that they are allocated to the lowest bids (i.e. the most competitive projects) coming from anywhere in the EU. This is different to non-competitive flat rate subsidy (like the 45v credit in the US IRA), or a geographically confined auction financed with national budget, such as those having taken place in Denmark or the UK[4]. The good news is, we saw from the results of the first round that the EU has some genuinely competitive renewable hydrogen production conditions. The winning bids cleared at an average subsidy of 0.4€/kg, less than 10% of the ceiling price set for the auction, roughly 10% of the estimated price delta between renewable and fossil hydrogen, and a fraction of the subsidy paid in comparable schemes. For reference, the US 45v credit is up to $3/kg, the UK’s first auction cleared at $12/kg, and the Danish auction cleared at $1.18/kg. The Figure below illustrates the bid prices from projects submitted to the first round of the EHB, where all the winning bids came from the Iberian Peninsula or the Nordics. This is unsurprising given these are areas with the cheapest renewable energy, the most important variable in the production of renewable, electrolytic hydrogen.

Now for the not so good news. Although the EU has some centrally controlled funds, such as the Innovation Fund that finances the EHB, these are relatively small and spread quite thinly. Knowing this, the EU allows for Member States to step in with national budget to clear domestic projects that were unsuccessful in the geoagnostic, competitive auction, they call this ‘auctions as a service’. This is in principle a brilliant way of getting more funds into the sector, and ultimately incentivising more production. However, inevitably it has the effect of distorting the development of the market towards the economically powerful incumbent industrial powers, not necessarily towards the most truly ‘competitive’ projects. Perhaps predictably then, the only Member State to make use of the auctions as a service in the first round of the EHB was Germany, who contributed €350m to fund domestic projects. These German projects cleared at a subsidy rate of €4.7/kg, 11x the price of the geoagnostic projects. €720m allocated in the geoagnostic auction will deliver 150,000t of clean hydrogen per year, for 10 years, whilst the German projects will produce roughly 5% of that for roughly 50% of the equivalent budget. In the meantime, genuinely competitive projects in Greece, Portugal, Finland, Spain, etc will go unfunded and likely disappear. This feels reminiscent of the data on the unproductiveness of European solar panels referenced in Figure 4, and again the reason is the same. Germany has roughly double the installed solar capacity of any other Member State in the EU, whilst most of the US solar capacity is in regions with high irradiation (high productivity), like California and Texas.

From the European perspective, one conclusion to draw from these results is that Europe is failing to capitalise on its genuinely competitive conditions because financing and decision-making processes are too Member State centric. This is allowing powerful incumbents to resist changes in industrial geography associated with a modernisation of the economy. Over the short-term incumbents may be able to use their fiscal power to artificially sustain these industries, but in the mid to long-term it is arguably not financially sustainable and may result in the EU missing its chance to gain any enduring foothold in these new growth industries. This is just one reading of these results, and we should be careful not to draw the wrong conclusions. It is first and foremost a good thing that Germany have installed a lot of solar and that they are committing funds to the clean hydrogen sector. The problem is if this remains the only story of European innovation and modernisation.

Returning to positive news. In the second round of the EHB auctions, the EU introduced some new conditions, which seem to go in the direction of ‘mission-driven’ policy approach. Firstly, they introduce local content requirements[1] for electrolysers, one of the key technologies for hydrogen production projects. A politically brave and relatively unprecedented decision that should support European electrolyser manufacturers, ensuring some ‘spill-over’ advantages, even if it potentially increases the cost of the hydrogen itself. Secondly, they increased the budget substantially to €1.2bn, showing risk taking and ambitious intent from the public sector. Thirdly, they ‘ring-fence’ some of the budget for key sectors that they consider to be highest value-add, namely maritime and aviation. This market intervention goes against conventional economic wisdom to let the market self-select for the highest willingness to pay (the logic of the first auction), and rather shows ‘market-creating’ behaviour and leadership on the part of the public sector. I would argue that these examples point towards a more horizontal (‘mission-oriented’) approach to policy design and intervention, consistent with the vision of Von der Leyen and Draghi, as well as the theory of policy design proposed by Mazzucato.

Conclusions

Europe is in a crisis of economic competitiveness that potentially threatens the fabric of the European social contract. There are certainly concerning signals for the future of competitiveness in net-zero aligned sectors like renewable energy manufacturing and the underlying tension between incumbents and innovators. Nevertheless, there are also very encouraging signals from pockets of genuinely competitive conditions, and, in my opinion, European leaders are making an attractive and exciting case for a more modern and unified Europe. I buy into the vision outlined in Von der Leyen’s Political Guidelines, her Mission Letters[2] to her Commissioners, and the sentiment behind Draghi’s report.

However, realising the kind of transformation required to go from the rhetorical sentiment of cross-sectoral synergies expressed in the European Green Deal or Horizon Europe, to something deeply transformative will likely require significant changes in the mechanics of the EU. Specifically, Draghi calls for changes in EU decision-making processes (e.g. veto rights), the collection and distribution of funds (e.g. much greater centralisation), as well as changes to the legal competencies of the EU institutions (e.g. military). These represent meaningful concessions of power and control on the part of Member States. This would be done on the promise of ‘the whole being stronger than the sum of its parts’, an extremely difficult political proposition. It is the task of EU leaders and proponents of a just and liberal-democratic Europe to sell this vision (or something similar) to national politicians as an attractive future that can then be sold on to their voters at a national level.

This is the challenge of making centrist, compromise politics attractive in the face of flashy and simple populist alternatives[3]. It is an extremely difficult proposition, perhaps only achievable in the face of a common crisis. Is the economic crisis acute enough? Perhaps not. In interviews since the release of his report, Draghi has referred[4] to the current economic prognosis as akin to a ‘slow agony’ rather than a cliff-edge collapse. You could say this is reminiscent of the relatively distant and impersonal nature of the climate crisis, something politicians have also struggled to effectively communicate the urgency of. Perhaps now combining the economic and climate challenges ‘horizontally’ can be more effective in rousing enduring coalitions of support.

[1] https://climate.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7fc59da6-15a1-46a1-a015-fa9645789601_en?filename=policy_funding_innovation_fund_if24_memo_qna_rfnbo_hydrogen_production_en.pdf

[2] https://commission.europa.eu/about/commission-2024-2029/commissioners-designate-2024-2029_en

[3] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-33238-9_11

[4] https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/draghi-urges-reform-massive-investment-revive-lagging-eu-economy-2024-09-09/

[1] https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1481986/cost-of-renewable-energy-versus-fossil-fuels-worldwide-forecast#:~:text=This%20price%20steadily%20increased%2C%20reaching,25%20USD%2FMWh%20by%202028.

[2] McWilliams, Kneebone, (2024). Lessons from the European Union’s inaugural Hydrogen Bank auction, Bruegel, https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/lessons-european-unions-inaugural-hydrogen-bank-auction

[3] Geoagnostic within the borders of the EU.

[4] Danish auction, UK auction.

[1] https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1481986/cost-of-renewable-energy-versus-fossil-fuels-worldwide-forecast#:~:text=This%20price%20steadily%20increased%2C%20reaching,25%20USD%2FMWh%20by%202028.

[2] McWilliams, Kneebone, (2024). Lessons from the European Union’s inaugural Hydrogen Bank auction, Bruegel, https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/lessons-european-unions-inaugural-hydrogen-bank-auction

[3] Geoagnostic within the borders of the EU.

[4] Danish auction, UK auction.

[1] See Von der Leyen’s ‘Political Guidelines’ or ‘Mission Letters’ to her new college of Commissioners.

[2] https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/funding-and-financing/recovery-and-resilience-facility-clean-energy_en

[3] https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/state-aid/ipcei_en

[4] See ‘Hydrogen in the Energy Transition’ for definitions of each production pathway.