Security of Supply: Gas

In this Cover the Basics article, we discuss what is security of supply? What does a security of supply risk look like? While also providing context to security of supply measures for gas in Europe over the years

What is security of supply?

The European Environment Agency (EEA) define security of energy supply as “…the availability of energy at all times in various forms, in sufficient quantities, and at reasonable and/or affordable prices.” In the context of gas security of supply specifically, the concept refers to the provision of gaseous energy, namely ‘natural gas’[1].

What does a security of supply risk look like?

Fundamentally, a threat to security of supply can be any development outside of the normal functioning of the gas market and network, either at a national, regional, or Union-wide level. Disruptions to gas supplies must be taken seriously as European consumers rely on gas for the provision of important social services and economic activities, including heating, cooking, and industrial applications.

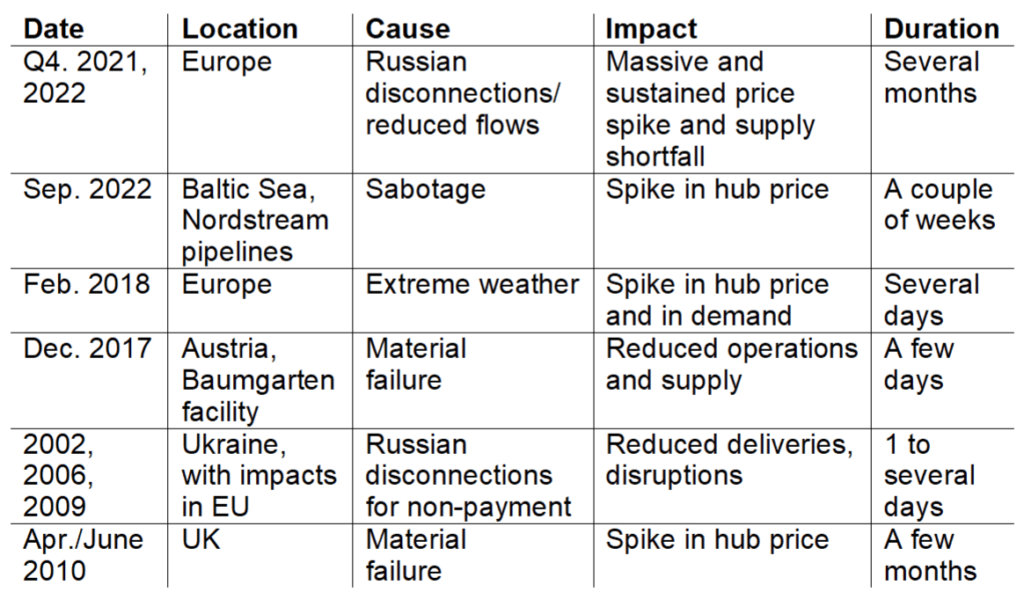

Typically, concerns regarding security of supply remain minor and localised, with the market quickly resolving them, sometimes with local intervention. However, as the European Union (EU) has a single market for natural gas and widely shared value chains (such as transmission pipelines and LNG terminals), impacts in one region are often felt across the bloc. This interconnectedness is also the basis for ensuring security of supply in the region, by building in capacity (and obligations) for solidarity provision between Member States. The table below includes an overview of some of the major security of gas supply disruptions that occurred in Europe in recent years.

As well as being directly combusted for heat or used as a feedstock, gas is also combusted to generate roughly 25% of the EU’s electricity, and as much as 50% in some Member States2. Moreover, in most EU countries gas is the ‘marginal supplier’ in the electricity mix – i.e. providing flexibility and covering the highest peaks in demand. This means that disruptions in gas flows can have cascading impacts into the electricity sector, particularly during times of peak consumption.

How vulnerable is the EU to supply disruptions of natural gas?

The EU uses natural gas for roughly 25% of its overall energy needs, around 80% of that gas is imported. The high share of imports creates a clear and fundamental dependency for Europe, exacerbated by the small set of suppliers that provide those deliveries. Before Spring 2022, roughly 40% of all gas imports originated from Russia, followed by Norway (16%), Algeria, Qatar, and others. Although high, the EU’s dependence on Russian gas is not an isolated case in the global context. This is because the vast majority of global gas production comes from the handful of countries that are well endowed with accessible natural gas deposits, limiting the scope to diversify trading partners and often creating dependencies.

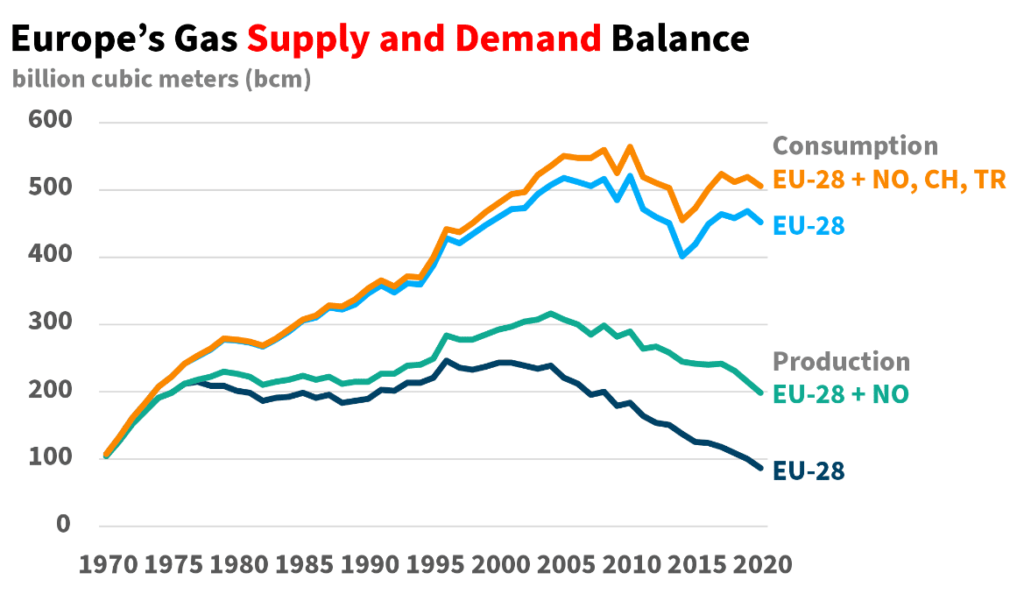

The EU used to satisfy virtually all its natural gas needs domestically, but production plateaued in the 1980’s and has fallen quickly over the past couple of decades, despite growing demand. The Figure below illustrates how this delta between production and consumption has massively widened since the late 90s, particularly if production in Norway and the UK were not accounted for.

Moreover, the EU imports around 75% of its gas via pipeline, an inflexible form of infrastructure that does not allow for redirection and trade with other partners. A high degree of reliance on this form of import capacity creates an interdependency between the exporter and importer. Whilst European gas purchasers cannot reroute pipeline capacity to other third-country exporters in the event of disrupted supply, the exporter also cannot reroute that pipeline capacity to another purchaser in the event of non-payment or reduced demand. In a rational decision-making scenario, these conditions encourage both purchasers and exporters to maintain trade through the infrastructure. However, energy can be a geopolitical tool and therefore has been subject to leverage for ideological or politically motivated reasons.

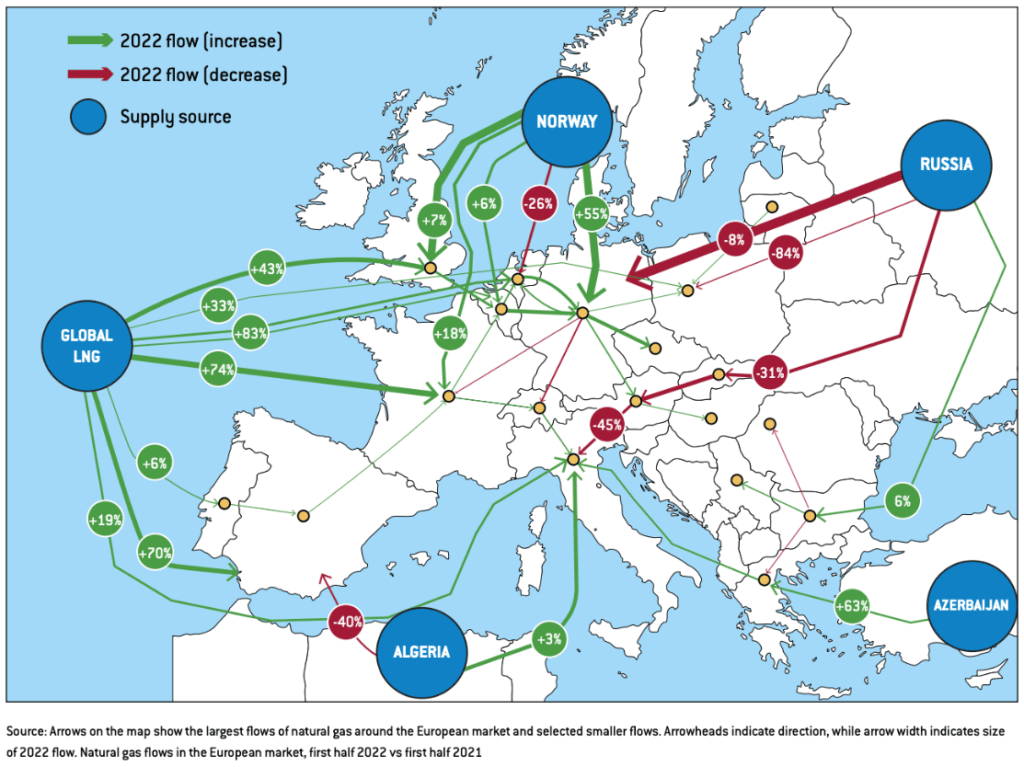

The Figure below outlines the main import routes into the bloc, and some key internal transmission flows, as well as indicating how flows of gas changed from the first half of 2021 to the first half of 2022.

By the end of 2022, the EU had significantly reduced its gas consumption and totally reconfigured the shares of trade with different suppliers. Norway increased exports to the EU, becoming the largest single supplier, whilst pipeline deliveries from Russia reduced to roughly one-quarter of the previous year. Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) overtook pipelines to become the new main source of gas, with deliveries from the US more than doubling, as well as larger volumes from Qatar, among other exporters.

LNG terminals are a useful form of flexible import infrastructure that allows for imports from a wider range of global suppliers. However, roughly 40% of the EU’s LNG import capacity is in the Iberian Peninsula, with bottlenecks in transmission capacity limiting export to the rest of the European grid. As a result of these kinds of limitations, it is not possible for the EU to entirely compensate for major and sustained shortfalls in pipeline gas flows with higher levels of liquid gas imports. Construction is planned for several new terminals close to demand centers, for example, in the north of Germany where previously there were none, as well as plans to better connect Iberian import capacity to the rest of Europe.

Where consistent flows of natural gas cannot be guaranteed, the alternative is to store volumes ahead of time to protect against sudden disruptions. EU-27 gas storage capacity is 1147 TWh (Terrawatt hours) (~100BCM (Billion cubic metres)) across 18 Member States, approximately 25% of EU annual gas demand. The storage capacity is unevenly distributed across the Union, with some Member States contracting capacity across borders and even in third countries such as Ukraine, where there is roughly an additional 30BCM of capacity. Most storage assets are used as part of the normal functioning of the market, for example, to cover the summer-winter price split. However, they also help buffer European consumers against supply disruptions, particularly during the winter months when demand is higher.

EU gas security of supply at a glance in 2023:

- The EU has a massive import dependency for natural gas;

- For the most part, pipeline infrastructure is tied to a given supplier;

- The global market is dominated by a handful of suppliers which means relatively low optionality and choice, even with flexible import infrastructure;

- Domestic storage is only sufficient to cover ~25% of annual demand;

- Natural gas represents a big share of electricity production, creating a risk of cascading energy insecurity;

- There are short-term measures that can be used to help reduce the impact of security of supply disruptions, including fuel switching and demand destruction.

A history of security of supply measures for gas in Europe

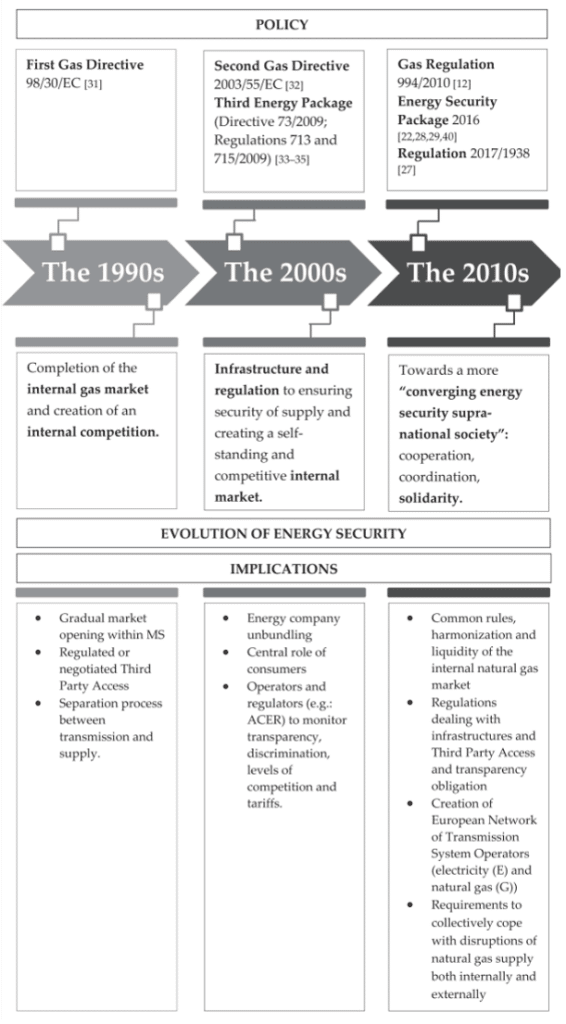

As demand for natural gas has increasingly outpaced domestic production, the Union has gradually introduced measures to try and safeguard against disruptions and to leverage the shared resources of the Member States to avoid critical shortages. These preventative and emergency measures have manifested in a series of regulations and texts.

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution in the security of supply policies since the 1990s, with the concept formally incorporated into European gas policy through Directive 67/2004. However, it wasn’t until the first formal ‘Security of supply Regulation’ in 2010 that reinforcing the resilience of European gas supplies became a clear shared goal of the Union.

The Regulation was drafted with the intention of maintaining supply of gas to European consumers, even in the event of a market failure. As such, the Regulation created a system of ranking disruptions as (i) early warning, (ii) alert, and (iii) emergency level, with corresponding measures at each stage. At the emergency level, the market is deemed to be unable to resolve the problem without intervention, and the European Commission is empowered to step in. Amongst other things, the Regulation also introduced ‘stress-tests’ to be completed by ENTSOG (European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas), which model the impact of different disruptions.

Regulation 994/2010 was subsequently revised in 2017, with the introduction of Regulation 2017/1938 which focussed more on external geopolitical risks to supply. The Regulation introduced a ‘solidarity principle’[3], mandatory regional prevention and emergency plans, as well as four regional risk groups based on major transnational risks and supply routes in the EU[4].

The Security of supply Regulation has again been recently revised, with a version proposed by the Commission in March 2022 and subsequently adopted by the Council in June. This new text was prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the EU’s subsequent decision to place sanctions on the import of Russian energy products, as well as Russian state gas provider Gazprom’s decision to significantly reduce deliveries of gas to Europe. These factors have culminated in an exceptional and prolonged gas crisis in Europe, with prices rising 15x their pre-war levels and shortages in supply occurring in several Member States. This is an example of leveraging energy as a geopolitical tool, as mentioned earlier.

As such, this latest iteration of the security of supply Regulation focuses on adapting the functioning of the market, as well as specific provisions on storage. The focus on storage has been such that a dedicated Regulation on the subject was adopted, including a mandate for underground gas storage on EU countries’ territory to be filled to at least 80% of their capacity before the winter of 2022/23 and to 90% before the following winter periods.

The latest regulatory frameworks and voluntary initiatives in Europe for gas networks point to a highly coordinated future, with the imperative of security and solidarity within the Union emphatically underlined by the gas market conditions in Europe during 2021-2022. Although the EU is a major importer of natural gas and will likely always be, to an extent, dependent on energy imports, the coordination and cooperation for allocating resources once inside the bloc are stronger than ever.

Germany is right on Nordstream2.

⁰The pipeline has to be assessed in light of the security of energy supply for the whole of Europe.

⁰We are still too dependent on Russian gas.

⁰We have to strategically diversify our suppliers and massively invest in renewables. pic.twitter.com/RrKUZyCTSx— Ursula von der Leyen (@vonderleyen) February 22, 2022

If you still have questions or doubts about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

James Kneebone, Ilaria Conti, Marzia Sesini

Notes

[1] ‘Natural gas’ is the term used to describe the largely methane-based gas that is the predominant gaseous vector in our energy mix. In the future, the concept of ‘gas security of supply’ may be broadened to include other gases, including hydrogen and synthetic gases, if they grow to occupy a meaningful share of our final energy demand.

[2] For example, Italy (50.98% in 2021).

[3] Fundamentally the obligation to share gas with neighbouring countries in the event they suffer a critical shortage of gas.

[4] For more detailed information on these two iterations of security of supply’s regulation see Sesini, et al., 2022.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights