Retail competition and electromobility

This is the third instalment of the Topic of the Months: Energy and Transport regulation, links between the sectors

Introduction

Since the mid-1990’s, the European Union has embarked in the reform of the energy sector with the aim of introducing competition in generation and supply, to promote efficiency and innovation.

Retail competition is expected to provide greater choice and cost-reflective prices to EU energy consumers. Even in the case of a homogeneous product like electricity, innovation and differentiation may develop in the commercial terms and in the bundling of electricity supply with other products and services, including, for example, aggregation for participation in demand-response/flexibility programmes.

In this respect, since July 2007, all consumers in the EU, irrespective of their size, and therefore also household consumers, have the right to choose their suppliers[1]. In fact, consumers may now choose more than one supplier and have more than one supply contract[2].

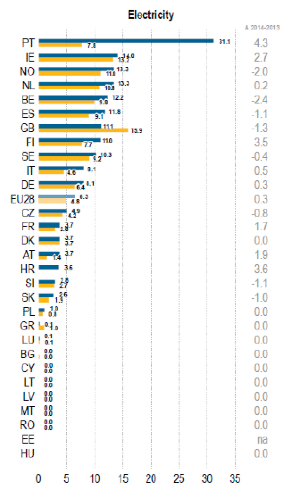

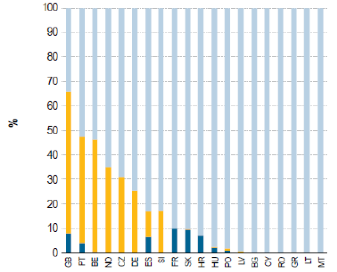

Consumers, and in particular, household consumers, have been slow in taking advantage of the possibility of switching supplier with the aim of getting better conditions for the electricity they consume[3]. For many years after 2007, switching rates have been trailing at 5-6%, as shown in Figure 1, implying that the average consumer switched supplier every 15-20 years – much less frequently than for most other goods and services –, even though the impression was that the average reflected a small number of consumers switching much more frequently and a large majority not engaging in switching at all.

Figure 1 – Switching rates, in percentage, for electricity household consumers in 2008-2013 (average, in yellow) and 2014 (in blue)

Source: ACER/CEER Market Monitoring Report 2015

As a result, in 2014, i.e. seven years after full retail market liberalisation, in only 7 out of the 28 EU Member States, more than 10% of household consumers were served by a supplier other than the incumbent, that is the one which was serving them before liberalisation, as shown in Figure 2[4].

Figure 2 – Proportion of electricity consumers with a different supplier than their incumbent supplier

Source: ACER/CEER Market Monitoring Report 2015

Non-household consumers have been somewhat faster in taking advantage of the opportunity to switch to a supplier offering better supply terms, but again not as fast as one could have expected, and data is less readily available.

One of the main reasons for the low switching rates for household consumers has been the perception that the monetary benefits of choosing a different supplier were limited[5].

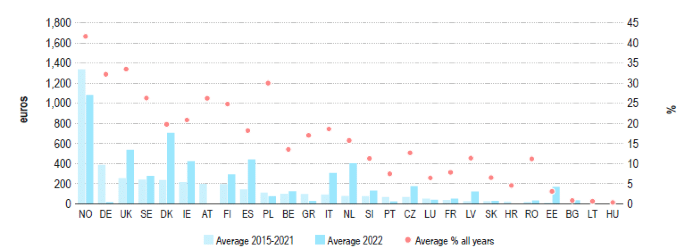

With the sharp increase in electricity prices since 2021, the saving potential of switching supplier has correspondingly increased, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Average monetary savings for electricity household consumers from switching supplier: 2015-2021 vs 2022

Source: VaasaETT, reproduced from ACER/CEER Market Monitoring Report, Energy retail and Consumer Protection Volume, 2021

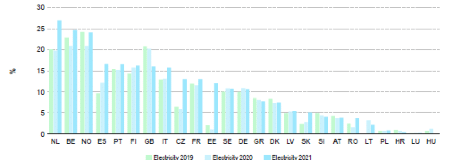

As a result, consumers started more seriously to consider the option of changing supplier, with the result that switching rates have significantly increased in most Member States, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Switching rates for electricity household consumers in 2019 – 2021

Source: ACER/CEER Market Monitoring Report, Energy retail and Consumer Protection Volume, 2021

In order to ensure that competition can fully develop and it is not hindered by possible conflicts of interest of network operators also active in the generation and/or supply business, unbundling requirements have been imposed on energy sector undertakings. These requirements changed over time and, in general, have become progressively more stringent[6]. For transmission system operators, the default requirement is ownership separation, with alternative settings possible for undertakings which were still vertically integrated in 2009. For distribution system operators, the default requirement is legal separation, with derogations for small operators.

Unbundling rules are complemented by Third Party Access requirements which oblige network operators to allow access and use of the network, at non-discriminatory conditions, by all market participants wanting to buy or sell electricity.

In the previous episodes of this Topic of the Month[7], we considered the current practices for the procurement of traction current in the railway sector and the development of electric vehicles. In what follow we consider these two aspects in turn, assessing how the energy sector provisions regarding retail competition and unbundling should apply to them.

The procurement of traction current for the railway sector

As seen in one of the previous episodes of this Topic of the Month, despite the right of electricity consumers freely to choose their suppliers, in many jurisdictions railway operators are still bound to buy the electricity they need to power their trains from the railway infrastructure manager. The compliance of this practice with the electricity sector rules is clearly dubious. Various reasons have been given for this limitation, including the lack of metering capabilities at the level of the individual trains. This justification is however difficult to comprehend. In fact, as soon as multiple operators run trains on the same infrastructure, the need to account consumption for the trains of the different operators, and therefore of the different trains, arises. At the moment, it seems that in those cases where trains are not individually equipped with metering devices, such accounting is performed by estimating consumption based on the composition and weight of the train, the performance of the traction material and the profile of the route plied[8]. Clearly, the same approach could be used to support the possibility of different train operators buying electricity from different suppliers. These suppliers would nominate withdrawal from the electricity transmission or distribution networks into the railway infrastructure manager’s electricity network[9] on the basis of the consumption profile provided by the train operator, in the same way as any other large electricity consumer. As two networks with third party access would be involved, the transaction would involve balancing requirements on the two networks, conceivably more complex than in the case of consumers directly connected to the transmission or distribution networks. However, such complexity should not be used to prevent retail competition to be extended to what, in most jurisdictions, are the largest electricity consumers. Moreover, in some countries train operators are already able to choose their suppliers and therefore the technical and administrative complexities have been overcome.

The regulatory regime of electric vehicle charging stations

We now turn to electric vehicles, which is a new and fast growing source of electricity demand. As indicated in one of the previous episodes of this Topic of the Month, one of the main technical challenges facing the electric vehicle industry is to improve the performance of these vehicles, especially in terms of the maximum range with a full charge, and reduce the battery recharging times[10]. From an infrastructure perspective, the challenge is to develop a network of recharging stations which adequately cover the whole road network and provide sufficiently fast charging. From a regulatory perspective the obvious question is therefore what is the regime applicable to recharging stations. The answer to this question rests on the regulatory qualification of the charging poles. Should they be considered as part of the network, and therefore a shared facility, or should they just be considered as a consumption unit, in which case, however, the electricity will be resold to the electric vehicle driver?

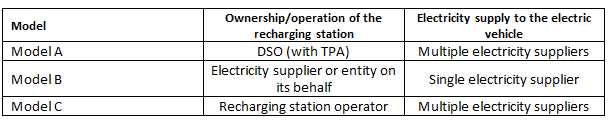

In general, three possible models can be identified[11]:

- The charging station is considered as part of the distribution network and therefore subject to third-party access rules. Therefore, it can be used by any supplier to deliver electricity to the electric vehicles of its customers;

- The charging station is not considered as part of the network, but it is operated by an electricity supplier or another entity on its behalf on an exclusive basis. This model mimics the current standard setting of most petrol stations, which are single-brand outlets;

- The charging station is not considered as part of the network, but it is operated by an (independent) operator allowing multiple suppliers and their customers to use it.

The following Table shows the different settings of the three models.

Note that in the EU legislation, Model A is considered as an exception[12], although, strictly speaking, such a Model would not breach the general unbundling rules since the distribution system operator would not be involved in selling electricity, but only providing the infrastructure for delivering such electricity, in the same way as it provides the grid to deliver electricity to consumers’ sites.

The most appropriate model mainly depends on the number of recharging stations which could be established in any local area, the relevant market, using terminology from the competition practice. In fact, in the case of charging stations, the usual argument for monopoly infrastructure with third-party access, based on the cost structure and economies of scale, does not seem to hold, as it does not hold in the case of traditional petrol stations. Therefore, competition may be extended to the provision of recharging services (as it is the case with petrol filling stations). And while electricity is a fully homogeneous product[13], electricity recharging services can offer opportunities for differentiation, for example in the charging speed. Therefore, wherever a sufficient number of charging station can be established in the local area/relevant market[14], Models B seems a possible setting, with electricity suppliers competing both in selling electricity and the recharging service. Where instead the number of charging points in the local area is limited – e.g. in urban area where space might be limited, Models A or C might be better options, as they allow competition in the provision of electricity through a single recharging infrastructure. Between these two models, Model C would allow the limited number of sites available in the local area/relevant market to be assigned through a tender process, while Model A would rely on traditional regulation to ensure that the limited competition in charging services does not result in excessive recharging fees; it is allowed under EU rules in those cases where there are no other parties interested and available to develop charging stations[15].

As a final remark, the role of regulated DSO-operated recharging stations might be important in solving the ‘chicken-and-egg’ problem of the growth in the number of electric vehicles and the development of a sufficiently granular network of charging stations[16]. In fact, there might be a reluctance to develop such a network until demand for charging services commercially justifies it, but drivers might be discouraged to buy electric vehicles until such a granular network is available[17]. This is why EU rules allow distribution and transmission system operator to own, develop, manage or operate recharging points for electric vehicles as an exception to the general unbundling provisions, to kick-start the development of electric vehicle charging networks.

[1] Article 21 of Directive 2003/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2003 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 96/92/EC. An equivalent provision is now contained in Article 4 of Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on common rules for the internal market for electricity and amending Directive 2012/27/EU (recast)

[2] Article 4 of Directive (EU) 2019/944.

[3] The same has been the case for gas.

[4] Note, however, that the switching rate in itself is not a reliable indicator of the attitude of consumers towards retail competition. In fact, it might well be that, if there is sufficient competition in the supply business, all suppliers, including the incumbent, end up offering similar terms and therefore consumers can benefit from competition even without switching away from the incumbent. However, data provided by ACER show that, for example, German electricity consumers in 2015 used to switch at an annual rate well below 10% despite annual savings in the order of 350-400€ could be achieved by switching from the (see standard offer of the incumbent to the best alternative offer (ACER Market Monitoring Report 2015 – Electricity and Gas Retail Markets, Figure 19).

[5] Other reasons mentioned by consumers to explain the low switching rates included the lack of trust on alternative suppliers, the loyalty and satisfaction with the incumbent supplier and the perceived complexity of the switching process.

[6] For more details on the unbundling rules in the EU energy sector, see FSR, Cover the Basics, Unbundling in the European electricity and gas sectors, available at: https://fsr.eui.eu/unbundling-in-the-european-electricity-and-gas-sectors/.

[7] REF HERE.

[8] Note that this approach to estimating electricity consumption of different trains is not compatible with the participation of train operators in demand-response schemes. Such participation might be difficult to be envisaged for passenger train operators, but conceivable for freight train operators.

[9] The qualification of the railway infrastructure manager’s electricity network is not totally clear. It seems unlikely that it can be qualified as a ‘closed distribution system’ according to art. 38(1)(b) of the Electricity Directive, since this would require that the system distributes electricity primarily to the owner or operator of the system or their related undertakings within a geographically confined industrial, commercial or shared services site, where ‘related undertakings’ refer to affiliated undertakings as defined in point (12) of Article 2 of Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (18), and undertakings which belong to the same shareholders, which is typically not the case of railway companies.

[10] For more details on the electric vehicle charging, see FSR, Cover the Basics, Electric Vehicle Charging, available at: https://fsr.eui.eu/electric-vehicle-charging/.

[11] This is similar to the classification used by the Italian National Energy Regulator, AEEG, now ARERA, in selecting demonstration projects for electric vehicles public charging stations, as part of a five-year pilot programme launched in 2010.

[12] See Article 33(2) of Directive (EU) 2019/944: “Distribution system operators shall not own, develop, manage or operate recharging points for electric vehicles, except where distribution system operators own private recharging points solely for their own use”.

[13] And therefore, competition through product differentiation, as in the case of different grade of fuels in petrol stations, is not possible.

[14] This could be facilitated by installing charging stations in the courtyards of petrol stations. However, the relevant market for electric vehicle charging might be smaller than the one of traditional petrol station, given the still shorter range of most electric vehicles when compared to their internal combustion engine equivalents.

[15] See Article 33(3) of Directive (EU) 2019/944.

[16] A specific challenge for the development of fast-charging stations is the development of a sufficiently strong electricity network and/or electricity storage infrastructure to manage the high power demand of these stations.

[17] “When consumers consider buying their first EV, therefore, many have “range anxiety”—wondering if they will be stranded on the highway as gas-powered cars sail by. In fact, a June 2021 survey led by Nissan revealed that “56% of European internal combustion engine (ICE) drivers who are not considering buying an EV believe there are not enough charging points. Simultaneously, potential investors in EV charging points (CPs) or other EV infrastructure are hesitating until more electric vehicles are sold, creating a financing gap.” Excerpt from www.bcg.com/publications/2021/electric-vehicle-charging-station-infrastructure-plan-for-governments.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights