Performance and Prospects of the EU Green Deal

This is the first instalment of the Topic of the Month: The EU Green Deal: taking stock and looking ahead

The Origin of the European Green Deal

The EU Parliamentary Elections, which will be held from 6-9 June 2024 across the European Union, will shape and indeed constrain the next Commission’s room for manoeuvre, particularly when it comes to decision-making regarding environmental and climate change policy. This is why, in the April 2024 edition of the Topic of the Month, we take a closer look at the Commission’s European Green Deal (EGD) flagship project. In this post, we trace its origins and implementation to date, while future instalments focus on some of the Green Deal’s most recent policy initiatives and examine the challenges that lie ahead.

The European Commission presented the European Green Deal almost five years ago.

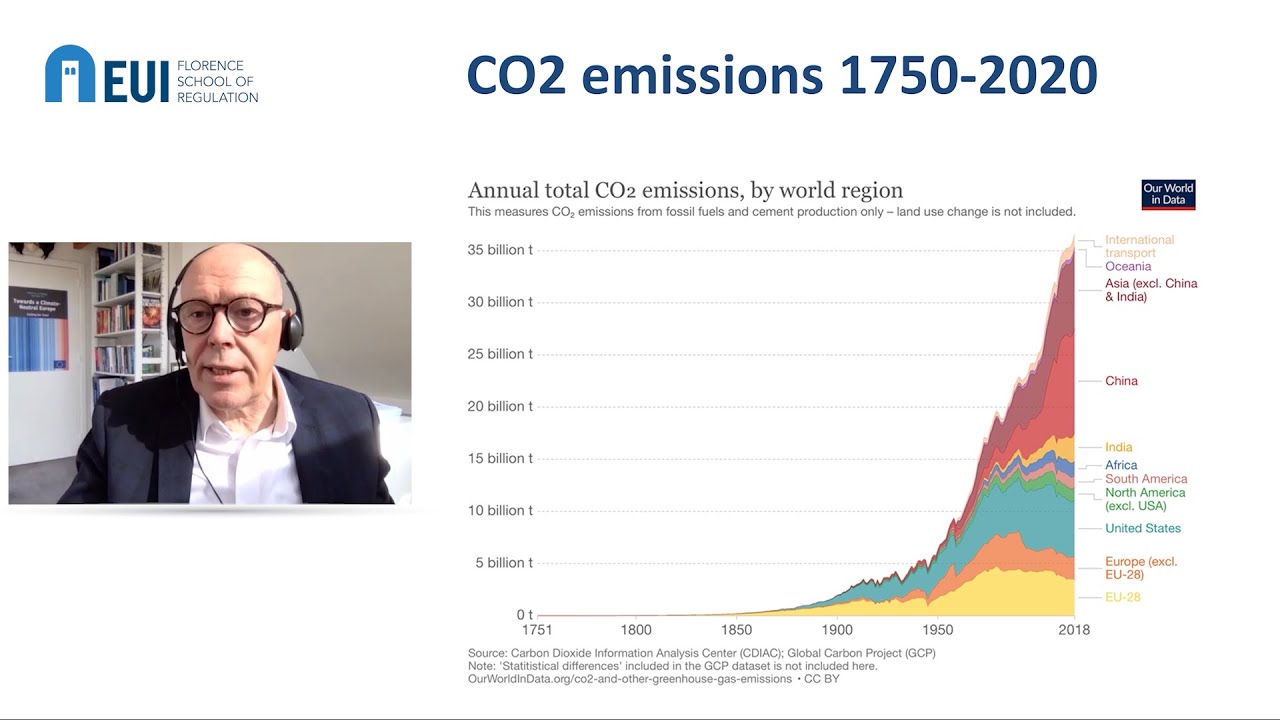

This project was already at the heart of the speech that Ursula von der Leyen gave to the European Parliament in July 2019 when she emerged as candidate for the Commission presidency. In her speech, von der Leyen identified planetary health as the ‘most pressing challenge […] the greatest responsibility and opportunity of our times’. It was also a project that suited the political moment: this occurred against the background of United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement (announced by then-President Trump in June 2017 and formally initiated in November 2019), as well as increasing domestic pressure to act more decisively on climate change through movements such as the Fridays for Future protests. Von der Leyen promised bolder EU action on climate change and environmental issues to obtain the support for her candidacy from the European Parliament. This included a pledge to strengthen the EU’s climate target for 2030.

Von der Leyen became Commission president during the Summer of 2019. When the new Commission formally presented its plan for the Green Deal in December 2019, it was billed as a new growth strategy for Europe and a dedicated roadmap to make the EU economy sustainable and achieve climate neutrality by 2050. While building on previous EU law and policy in the climate sphere, most notably the Juncker Commission’s A Clean Planet for All strategy, which had already introduced the idea of EU carbon-neutrality by 2050, this was the first time that sustainability objectives were explicitly placed at the centre of all decision-making in the Union. The Green Deal has since been followed up through multiple EU laws and strategies across a number of sectors. The implementation of all this is an ongoing process that will continue towards 2030 and beyond.

Now, almost five years after the introduction of the Green Deal, what can we say about how the Commission’s vison has played out in practice? We offer three observations.

1. The Green Deal is Now Anchored in EU Law

As promised by Ursula von der Leyen in her speech as candidate for the EU Commission presidency, a proposal for a European Climate Law was put forward by the Commission soon after her election, and subsequently entered into force as Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 in July 2021. The aim was to complement the existing 2030 Climate and Energy Framework by setting the long-term direction of travel towards 2050 and turning the political Green Deal commitment to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 into a legally binding obligation. The Climate Law increased the EU’s 2030 decarbonisation target from 40% to a more ambitious 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions relative to 1990 levels. It also put into place a monitoring-and-reporting system to ensure that Member States are aligned with these objectives, which builds on the mechanism of National Energy and Climate Plans introduced by the Juncker Commission in Regulation 2018/1999. As will be explored in a later instalment of this series, the Climate Law also obliges the Commission to propose an intermediary emissions reductions target for 2040 on the way to carbon neutrality in 2050. The regulation further established stronger, external oversight and evaluation of efforts to achieve these targets by setting up an independent European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change composed of 15 senior scientific experts with broad expertise, which provides independent scientific advice and issues reports on existing and proposed EU measures.

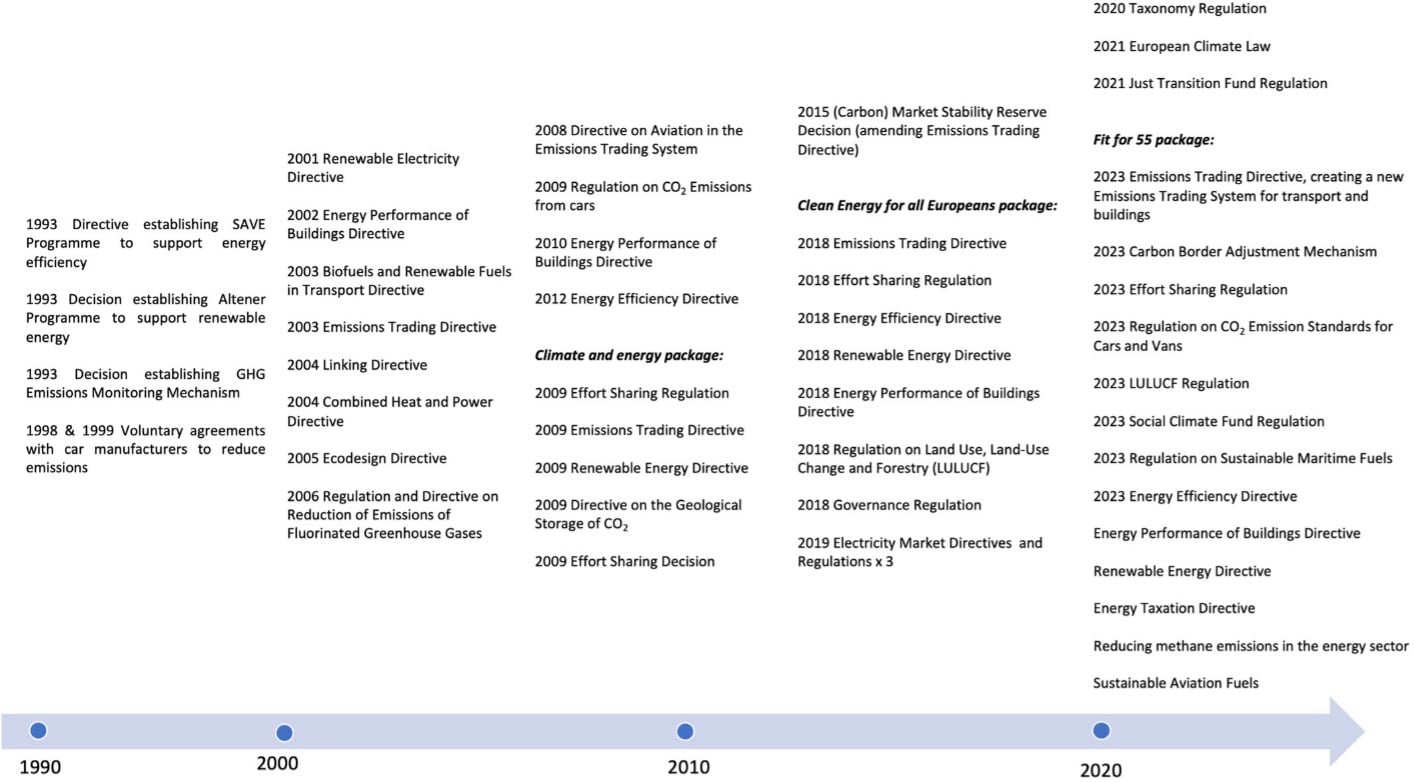

Figure 1: Principal EU energy and climate measures (Source: Dupont et al., 2024)

Under the umbrella of these new, overarching decarbonisation obligations, the Commission then began to commit its more detailed plans for the execution of the Green Deal into law, chiefly through the 2021 package of proposals, entitled Fit for 55. The Fit for 55 package is a major overhaul of the EU’s energy and climate laws, updating and expanding the EU’s existing legislation which before then had governed the EU’s climate action to 2030 (see Figure 1 for an overview of the sequencing of principal EU energy and climate law). This included updating energy, climate and transport legislation that had previously been revised as recently as 2017-2019. The Fit for 55 package was presented by the Commission in two tranches: a first set of legislative proposals in July 2021 was followed in December of the same year by proposals aiming principally at the decarbonisation of the gas sector. The package included measures to overhaul the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), the Effort Sharing Regulation for sectors not covered by the ETS, the Renewable Energy Directive (RED), the Energy Efficiency and Energy Performance of Buildings Directives, the Regulation on Emissions from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF), an update of the EU’s gas market acquis to accommodate the introduction of decarbonised gases and hydrogen, as well as measures to decarbonise road, air and maritime transport. A major legislative innovation of the package was the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), designed to address carbon leakage. All Fit for 55 files have now either been adopted or reached the stage of political agreement, apart from the Commission’s efforts to revise energy taxation, which are still stuck in the legislative process.

2. Crisis as a Catalyst: The Green Deal is Resilient

While undergoing this legislative evolution, the Green Deal has shown remarkable resilience to the crises that the EU has faced in parallel. When it was launched in December 2019, nobody could have predicted the COVID-19 pandemic that would bring the EU (and the world) to a standstill just four months later, as well as the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. On top of this came a growing subsidy race with increasing economic protectionism (as symbolised by the US Inflation Reduction Act in 2022) as well as new tensions with China on trade issues. These crises were stress tests for the Green Deal’s ability to continue pursuing its objectives without being eclipsed by pressing economic and energy security issues, which could have resulted in fragmentation and a decline in climate ambition.

The European Green Deal, however, provided a convincing narrative that decarbonisation should be a catalyst, rather than a hindrance, to economic recovery, energy security and global competitiveness. The Commission’s May 2022 REPowerEU Plan was a key instrument in this effort, and from its very inception emphasised the synergies between security and sustainability. The execution of REPowerEU thus saw an increase in the EU’s 2030 headline targets for energy efficiency and renewable energy, the former increasing from a 9% improvement relative to a 2020 baseline scenario proposed in the Fit for 55 package to an 11.7% improvement, while the latter increased from 40% to 42.5%. Further, many of the temporary emergency measures that were brought in as part of REPowerEU to stave off the immediate impact of the energy crisis have now been mainstreamed into permanent EU law. This includes the natural gas demand aggregation and joint purchasing mechanism through the AggregateEU platform, which will become part of the revised Gas Markets Regulation, as well as measures for expedited permitting of renewable energy installations, which have been included in the amendments to the Renewable Energy Directive.

REPowerEU also strengthened the link between crisis responses. While climate action has always been part of the EU’s NextGenerationEU instrument for lessening the economic impacts of the pandemic, the addition of dedicated REPowerEU chapters to the Recovery and Resilience plans creates an even more concrete link between sustainable energy security measures and financial support for economic recovery. Finally, REPowerEU also led to a closer consideration of the EU’s strategic dependencies in clean tech supply chains, resulting in proposals for dedicated legislation to bolster the EU’s security of supply regarding key net-zero technologies and critical raw materials.

3. The Green Deal is Still Incomplete and Evolving

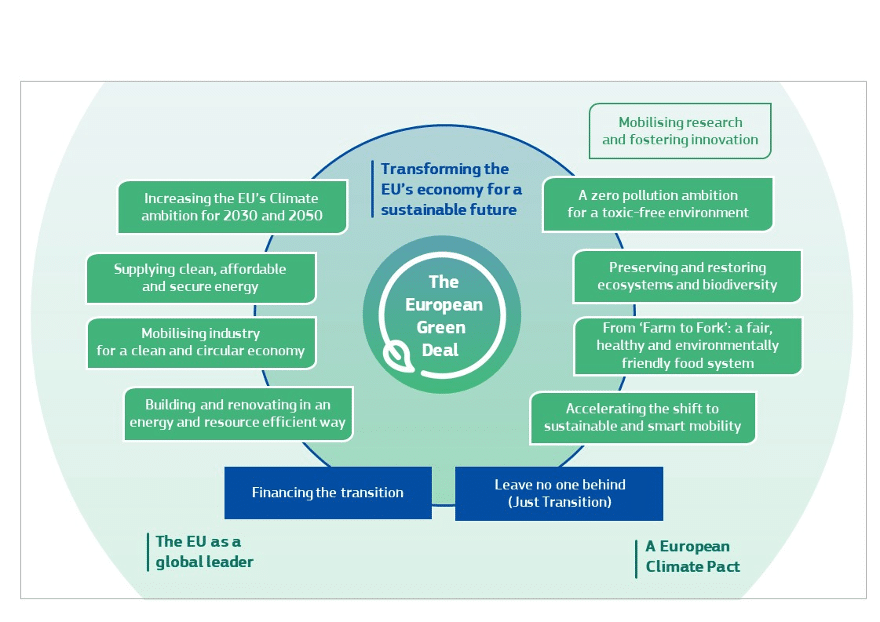

Though these developments in law and policy have introduced unprecedented changes, the Green Deal is far from complete. Through the passage of the Fit for 55 package, many of the core elements of what would traditionally be considered EU energy and climate policy are in place. However, the promise of the Green Deal is that of taking a much more comprehensive approach to decarbonisation, also including areas such as industrial competitiveness and environmental objectives as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Overview of the European Green Deal Strategy as envisaged by the Commission in December 2019 (Source: European Commission, 2019)

Some of these measures have only just begun their legislative journey, such as the proposals for a Forest Monitoring Law or an update of the rules on freight transport, which were both put forward by the Commission in the second half of 2023. Other initiatives are only now reaching the adoption and implementation phase after heated debate in the EU institutions, such as the Green Deal Industrial Plan, which will be the subject of a separate instalment of this topic of the month series. Yet others face an uncertain future after strong resistance from Member States, such as the controversial Nature Restoration Law.

Conclusion

As we approach the end of the current Commission’s term, it is remarkable how deeply ingrained in EU law and policy the Green Deal has become, and how resilient it has proved to challenges so far. Nonetheless, the Green Deal continues to evolve, and the next Commission will still have considerable influence on the shape and success of this flagship policy initiative. With the upcoming elections to the European Parliament, European leaders are discussing the EU’s priorities for the next five years. A green industrial deal might become the sequel of the EGD. Insights on the impact that the EGD had on how overarching climate ambitions would be followed up through specific EU legislation in different policy-areas offers lessons on how an overarching political initiative like an industrial green deal could shape policy-making in various areas over the coming years.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights