Is the Answer Blowing in the Wind?

Highlights from the debate: What is the optimal regulatory regime to connect offshore wind infrastructure to land?

Wind power has become a key driver of the energy transition, with the strategy for offshore renewables being one of the central pillars of the EU Green Deal.

The European Commission estimates that between 240 and 450 GW of offshore wind power is needed by 2050 to keep temperature rises below 1.5˚C. Electricity is expected to account for at least 50% of the total energy mix across the EU by 2050, with 30% of future electricity demand expected to be supplied by offshore wind. While the main focus is currently on near shore wind farms, the scale of ambition means we are moving deeper into the ocean and developing projects more akin to ‘wind islands’ between countries. How will the upscaling of wind farms and the new geographical positioning of them re-categorise them from a regulatory perspective, if at all? At what point do the electricity lines linking these large-scale ‘wind islands’ to shore become interconnectors? Should these lines be treated under the current regulatory regime or do we need to newly define such projects from a regulatory perspective?

As the European Commission is in the process of devising a new strategy for offshore renewable energy, in the second webinar in our ‘FSR Debates’ series, we explored the many questions surrounding the regulatory regime for infrastructure which connects offshore wind farms to land.

Watch the debate recording:

Our discussions centred around three questions:

- Should such infrastructure be treated as a connection infrastructure for the wind farm or as a network element that would be subject to third part access obligations or as a direct line?

- Should regulatory measures be based on the distance of the wind farm from the shore or, as the wind farm is connected to more than one country, should it be treated as a connection infrastructure, as an interconnector between different countries?

- To what extent do the exemption conditions of Art. 63(1) of the Electricity Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2019/943) apply to this infrastructure if it is not deemed a new ‘interconnector’? What scope is there for national policy?

Our hosts Alberto Pototschnig and Leigh Hancher were joined in this debate by Joachim Balke (DG ENERGY), outlining the European Commission’s future offshore strategy, our own Pradyumna Bhagwat (FSR), presenting on the regulatory principles for meshed offshore grids, and a panel of experts, comprising Carsten Smidt (from the Danish national regulatory authority DUR), Dirk Van Hertem (KU Leuven), Anders Skanlund (ENTSO-E) and Ursula Prall (Becker Buttner Held).

We first considered what this strategy may look like before turning to the regulatory challenges that lie ahead.

Offshore renewables will be the fastest growing energy source both in the 2030 and 2050 framework, going from the current 12 GW to 70 GW by 2030 and roughly 300 GW by 2050. The newly proposed EU-wide 55% emissions reduction target adds further weight to these developments. To achieve this, we have to significantly widen the scope of offshore wind production and face the massive investment challenge such ambition poses, especially in light of current economic circumstances created by the COVID crisis. Offshore wind poses specific challenges, different from those of onshore wind, related to the need for a truly integrated energy system, something not currently in place. The development of offshore wind will need to be accompanied by enhanced system planning, which will have to be more cross-border, with a longer-term outlook, and be more closely integrated with other sectors. Alongside that, this rapid upscaling also requires a considerable acceleration of technological developments. In any case, offshore wind will require a greater level of meshed offshore grids, which would be more cost-effective and have less of an environmental impact. But what does this mean from a regulatory perspective? What kind of regime needs to be put in place and, ultimately, how should it be harmonised? We need to have a set of common rules for the market, an adequate support framework, and connection rules. What kind of distribution mechanism should be adopted? How can we devise an equitable cross-border cost allocation mechanism which will ensure everyone participates and is fairly rewarded?

Regulatory issues need to be addressed across the planning, investment, and operation stages of such a system.

From a planning perspective:

- How do we define it? Should it be deemed a hybrid asset or slotted into our current definitions?

- What kind of permitting processes should there be in place?

- Are there specificities in the cost-benefit analysis?

- What kind of onshore – offshore coordination should be envisaged? What will be the rules surrounding its location – for example, will there be a zonal approach to it? Who is responsible for providing access? Who is responsible for the grid access charges?

- What measures will be taken to ensure public acceptance of these lines?

- Who is responsible when it comes to the decommissioning of these lines?

In terms of investment planning:

- What tariffs are involved? And what revenue streams are available? And what are the incentives to build these lines?

- What is the cross-border cost allocation?

- What role will RES cooperation mechanisms play in the process?

- And who will own these offshore grid assets?

In terms of operation:

- What will be the bidding zone configuration?

- What kind of balancing mechanisms could be put in place?

- How will the power flows and grid constraints be managed?

One view discussed during the debate was that offshore wind does not need a specific regulation. Rather, it requires a market with the best possible level of competition and, to achieve this, different production facilities should not be treated differently. It was noted that the purpose of interconnectors is to improve the internal market by facilitating trade and competition between countries. If you define these offshore wind lines as interconnectors, you risk squeezing out production from low-cost production facilities which would benefit internal trade.

From ENTSO-E’s perspective, there are three key elements to an optimal regulatory regime: system operation efficiency, market design efficiency, and alignment with policy objectives, with the first two within their remit. At present, there are two single-purpose concepts: connecting markets with interconnectors and market coupling these connections, using all of the capacity for cross-border trade and, secondly, connecting wind to the home market and using all the capacity for the single purpose of connecting wind power to the home market. Both of these concepts have been successful and are fit for the future. However, we may also need more complex forms – dual-purpose concepts – to connect markets and connect offshore wind farms. This would reflect a new reality and new potential, physically and market-wise. Cable capacity would have to be shared in these scenarios. How can it be shared in an efficient manner? Two solutions were considered by ENTSO-E – an offshore bidding zone solution and a home market solution. Their conclusion was that the offshore bidding zone solution is preferable in terms of market design and system operations because it reflects the physical congestion and flows and recognises the dual-purpose concept, and also creates cooperation by competing for capacity. There would be competition between the two purposes, which in turn would lead to more efficient system operations. However, such a solution would provide less revenue for offshore wind schemes than the whole market solution.

A counter view to this was that there will likely be no demand in offshore bidding zones and thus we would be creating an artificial market. It may not make sense to have competition between two bidding zones when there is not an efficient market in one bidding zone. The problem is to find a price – to have effective competition between bidding zones, we need effective competition within bidding zones. It is unclear whether one could have offshore bidding zones if there is no demand there. Demand is needed in the zone to have a market price.

From the Commission’s perspective, there cannot be too much room for ambiguity as to which rules apply to which infrastructure. What needs to be done with offshore is similar to what was done in the 60s and early 70s with onshore wind. We need to steer clear of a ‘spaghetti bowl’ and set clear rules which are not only based on current scenarios with offshore wind farms, but rather take a more forward-thinking approach and envision a regime which could be applied in the coming decade.

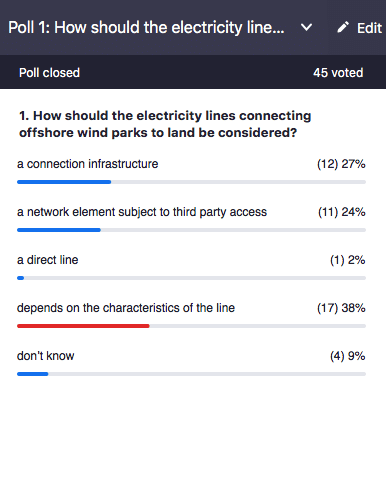

The views of our audience

To gauge our audience’s opinions, we launched two polls. The first poll, which asked how electricity lines connecting offshore wind farms to land should be treated, produced mixed results, with the majority feeling it depended on the characteristics of the line.

The overwhelming response (94%) to our second polling question was that the regulatory treatment of electricity lines depends on whether the wind farm is connected to more than one country and thus the electricity lines connecting it to shore also operate as interconnectors between different countries.

The EU strategy is expected in mid-November and the ensuing legislative proposals are expected by the middle of next year. With several fundamental questions remaining – not least, how to categorise these assets – it is clear that there are considerable hurdles in the path ahead.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights