Investigating the fundamental pillars of peer-to-peer energy and the legal issues it raises

Highlights from the online event: Peer-to-peer energy, what is it? And is it legal?

An exploratory debate on peer-to-peer energy

In the second event of the new #FSRinsight series, Professors Christoph Burger (ESMT Berlin) and Saskia Lavrijssen (Tilburg University) joined the FSR research team to discuss recent research on peer-to-peer energy from a regulatory and legal point of view.

The event was organised around two topics: What is P2P energy and what are the fundamental pillars that support its functioning? What are the legal hurdles that need to be dealt with to ensure P2P energy compliance with general rules on consumer law, e-commerce and liability?

Takeaways from the event

What is Peer-to-peer energy?

P2P energy is one of the buzzwords that populate the current public discourse on electricity. However, as it is often the case with buzzwords, consensus on a precise definition and its fundamental characteristics is still missing. P2P energy is usually related to the simultaneous trends of digitalisation, decentralisation and decarbonisation of electricity, but people have frequently different models in mind when they refer to it. Such heterogeneity is visible in the few cases of concrete implementation available so far. Among them, we can identify pilot projects led by universities at a local level or commercial offers available for all energy customers located in one country. In some cases, blockchain technology is used, while in others it is not. Residential prosumers are sometimes the only peers involved in the scheme, while in other instances small and medium-sized non-energy companies and organisations are included as well.

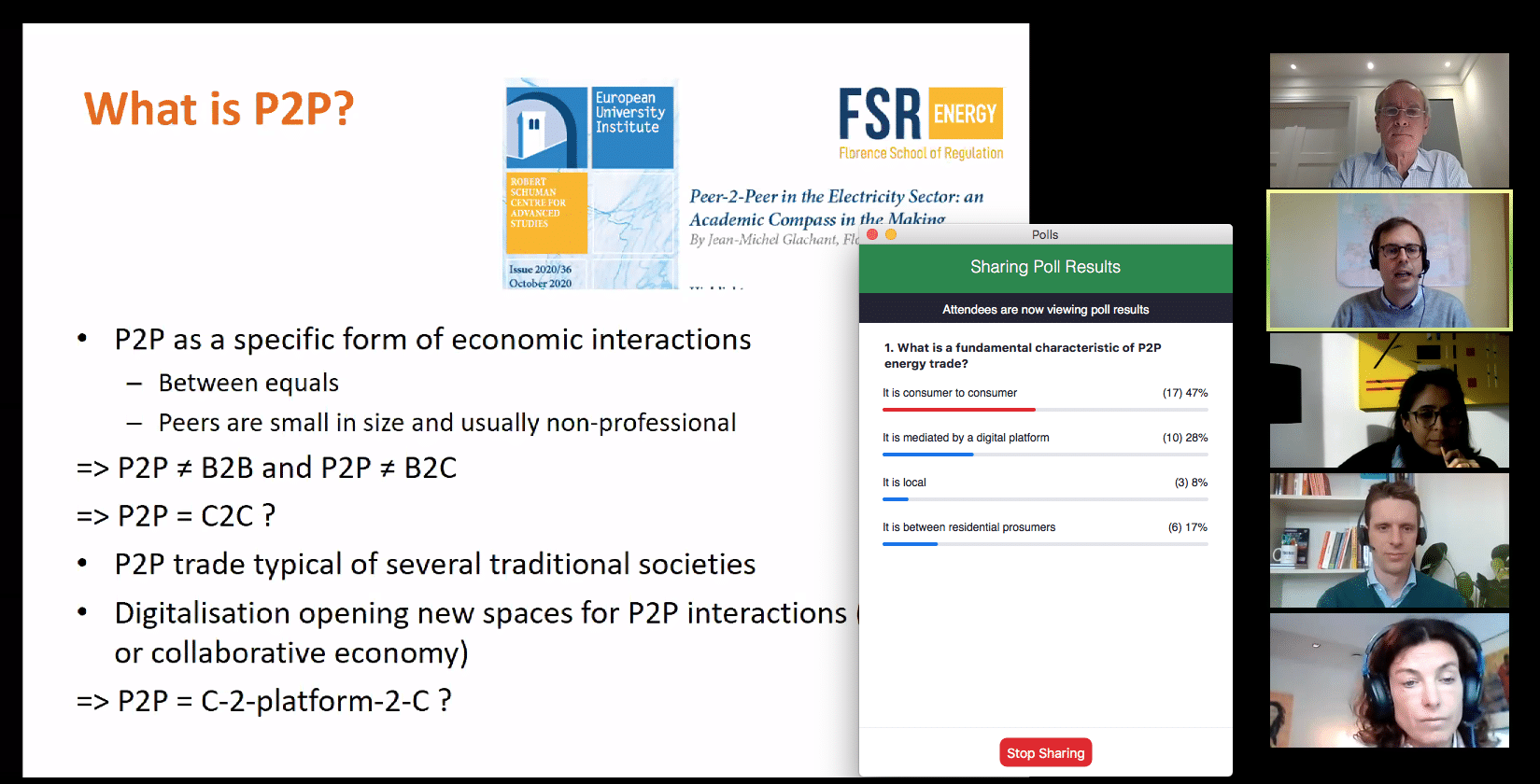

Confronted with such a differentiated landscape, we asked our audience what the fundamental characteristic of P2P energy is. Below you can find the result of the polling.

Our exchange of views with the discussants and the audience confirms that P2P energy is, first of all, a consumer to consumer relation. However, digital platforms play a fundamental role in enabling it, not only between small final energy consumers (e.g., households) but actually also between larger “peers”. Agreement seems to emerge also on the fact that P2P energy is potentially appealing for prosumers that would like to get a better price for the energy they produce, in particular if feed-in tariffs or net-metering is no more available, and for consumers that would like to make more informed consumption choices (e.g., buy local or buy green electricity).

Recently, within the framework of the Global Observatory on P2P, community self-consumption and transactive energy models (GO P2P), we looked at the fundamental characteristics of P2P energy and the implications for effective business models and sector regulation. In a recent policy brief, we observed that P2P energy refers, in its essence, to interactions between energy consumers and prosumers of a small size and for which energy is not the primary (professional) activity. As in many other economic sectors, three pillars are necessary to support the implementation of P2P energy:

- A pricing mechanism that defines the price of the energy exchanged and allocates the quantities available;

- A digital transaction loop that lowers the various costs attached to every transaction (e.g., the cost of identifying the right counterpart and settling the exchange);

- A delivery loop that ensures energy is supplied to the buyer according to the characteristics agreed in the trade.

However, the specific characteristics of electricity generate a series of challenges and call for an adaptation of the existing regulatory framework: without it, only certain versions of P2P energy are possible, while the others may be effectively blocked.

What are the legal hurdles?

Are there legal hurdles that could mitigate the robustness of the three fundamental pillars that supports P2P trading – pricing mechanism, digital transaction loop, and delivery loop? And if so, how could these legal barriers be overcome? The second part of the FSR insights brings a legal perspective to the analytical framework proposed in our policy brief (see also Almeida, Cappelli, Klausmann, van Soest forthcoming 2020). It complements it by raising three key issues grounded in legal measures outside sector-specific regulation – that is consumer law, e-commerce, and liability. It also concludes by proposing a policy recommendation that relies on the strategy of standardized pre-determined contractual terms and conditions.

- A price mechanism that defines exchanged prices in P2P trading is subject to different rules depending on who the peers are. If peers are consumers as defined by general consumer law – meaning, individuals or householders – a price mechanism must conform with the unfairness test as established by the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive. This means that algorithms that govern automated execution cannot create a significant imbalance to the detriment of the consumer.

- A digital transaction loop is made of platforms that enable P2P trading. Like other platforms outside the power sector, a digital transaction loop can be distinguished by the different pre-determined terms and conditions that apply to its users. These differences, in their turn, might affect the applicable legal regime. According to the interpretation of the e-commerce Directive, known as the Uber test, P2P trading platforms that match supply and demand and determine prices might not be recognized as information society service providers, but as suppliers. This is the case for most of the start-ups targeting householders as peers.

- A delivery loop reminds us that P2P energy trading depends on a physical infrastructure to dispatch electricity between peers. However, the liability risk for imbalances needs to be distributed between either the peers or the platform operator. The risk is allocated differently if the latter is recognized as an information society service provider or as a supplier.

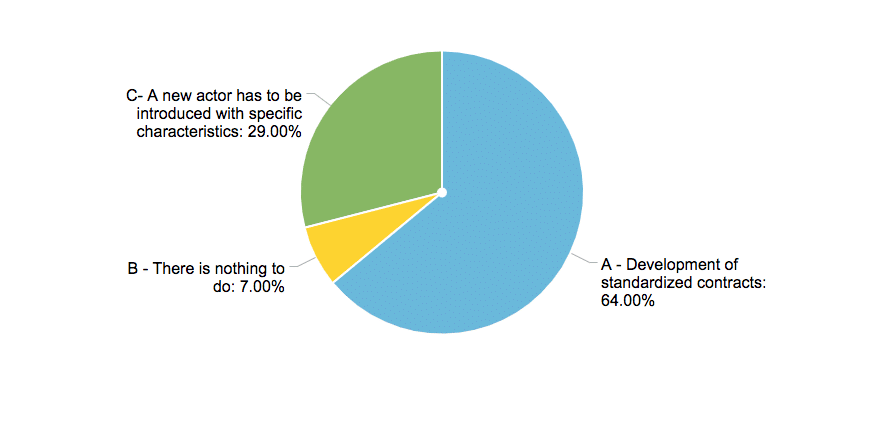

How can we better allocate the liability risk? Poll results

These legal issues bring us to a key conclusion. P2P trading platforms would be rarely recognized as an information society service provider if platform operators or software developers continue pre-determining the terms and conditions that apply to those using the platforms. Consequently, the heavy burden of network imbalance responsibility or the uncertainty of consumer complaints about the unfairness of the terms may deter new entrants and start-ups to the detriment of those consumers willing to engage more actively with energy. A way to overcome these legal barriers could be the standardization of pre-determined terms and conditions by regulators. This solution would remove from platform operators or software developers the decision-making of how to match supply and demand by the peers using the platforms and how to define prices. By doing so, P2P trading platforms could claim recognition as simple exchange platforms rather than suppliers.

Find more

Download the presentations of the event

Relevant links on peer-to-peer energy

Peer-to-Peer in the Electricity Sector: an Academic Compass in the Marking, FSR Policy Brief by Professor Jean-Michel Glachant (September 2020).

Peer-to-Peer Trading and Energy Community in the Electricity Market – Analysing the Literature on Law and Regulation and Looking Ahead, by Lucila de Almeida, Viola Cappelli, Nikolas Klausmann and Henri van Soest (forthcoming 2020).

Global Observatory on Peer-to-Peer, Community Self-Consumption and Transactive Energy Models (GO P2P), IEA Technical Collaboration Programme webpage.

Between new trading platforms and energy communities, Highlights of the second conference of the GO P2P (February 2020).

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights