Approaching electrification in last-mile communities with a gender perspective

An enabling environment for a gender-sensitive approach in the electrification of last-mile communities should be addressed through a structured framework for analysing multi-level contexts.

In this article, Rita Chiara Mele explains why addressing electrification with a gender perspective is urgent to scaling up the energy transition in rural communities and beyond.

Energy access and gender equality are inextricably linked. This is especially true in last-mile rural contexts in low and middle-income countries where the share of female-headed households with access to electricity is significantly lower than their male counterparts.

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), electrification in rural areas (26%) is far beyond urban rate (74%) (IEA, World Energy Outlook-2019). The most affected by this lack of energy are the marginalised groups of the communities, which are often women and their dependent children who are “disproportionately represented among the poorest and most vulnerable electricity consumers.”

This article provides an overview of the major bottlenecks faced by women without energy access through a multi-dimensional framework. The first section focuses on Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) coupling between gender equality (SDG 5) and energy access (SDG 7) in last-mile communities; the second section will analyse major bottlenecks hindering female empowerment and how electricity can overwhelm such hindrances from a small-scale entrepreneurial perspective. Finally, the third section will review viable measures for addressing female empowerment through a multi-level stakeholders’ approach.

The gendered nature of Energy Access

The gendered nature of energy poverty has multiple realms from private, business and public spheres. The link between gender equality, energy access and female entrepreneurship has been empirically analysed by ENERGIA Women’s Economic Empowerment programme (2014-2018) and by broad academic literature reviews (for a literature review on entrepreneurship, electricity and gender nexus, check out Enabling Equitable Access To Rural Electrification: Current Thinking And Major Activities In Energy, Poverty And Gender, and Inclusiveness by design? Reviewing sustainable electricity access and entrepreneurship from a gender perspective).

Electrification programs that incorporate a gender-perspective outline the role of women in providing valuable perspectives in intra-household energy-related decision-making. This includes contributing to eradicate poverty through female entrepreneurship up to mainstreaming gender approaches in policies, project management and financing.

Thus, an enabling environment for a gender-sensitive approach should be addressed through a structured framework for analysing multi-level contexts.

An enabling environment for a gender-sensitive approach should be addressed through a structured framework for analysing multi-level contexts.

As outlined by Danielsen, “access to energy is gendered” as women are often excluded from the decision making directly related to household activities, even though they are often the primary energy users.

Women lacking modern, reliable and sustainable energy services still, for instance, burn traditional biofuels. Around 40% of the world’s population cook with polluting stove and fuel combinations, causing significant respiratory diseases. The gathering of the biofuels (mostly carried out by women and children and weighing as much as 50 kilograms) can take up to 10 hours a week, thus impacting healthcare and access to education. Moreover, this time poverty reduces income-generating opportunities.

There are several caveats proving the multi-scale impacts of SDG 7 on socio-economic empowerment of women: powering social services such as dispensary to improve maternal health, public lighting to increase women safety and electrical water pumps to facilitate water fetching in last-mile communities.

Integrating women in intra-household decisions related to energy can lead to relevant changes in electricity choices: decisions on number and place of lights, willingness-to-pay, different uses of consumption and complementary appliances purchase are all aspects than can sensibly affect family livelihoods and their revenue. Thus, “slight shifts occur in multiple dimensions of daily life.”

Nevertheless, the impacts of energy access on gender equality can be measured not only on the final users’ perspective but also by considering women “as change agents in the energy sector.”

In this way, decentralized solutions as off-grid and stand-alone systems are recognised to be a more efficient solution rather than grid-connected options as their flexibility enable easily reaching isolated customers and to integrate women in socio-economic activities.

The need to go beyond the bulb

A gender-sensitive approach in electrification programs should not stop at the supply side but consider broader impacts on economic activities. Productive Uses of Energy (PUE) intended both home-based and in enterprise locations (according to Kapadia, we intend PUE as “utilization of energy – both electric and non-electric energy in the forms of heat or mechanical energy – for activities that enhance income and welfare”) represent a relevant entry point for economic opportunities in areas where market penetration is difficult.

Female participation in economic development, and explicitly in business activities, is still hampered by market and social barriers. Specifically, gendered social norms linked to household activities are determinants in deciding the gender division of labour.

According to the OECD, women spend two to ten times more on unpaid care work than men; this lack of recognition of the value and load of women’s work leads to a sensible disqualification of the role of women in participating in income-generating activities. Transforming this unpaid work as local brewing or baking and other home industries in income-generating activities would represent a viable business and empowerment opportunity for women living in last-mile communities.

Moreover, the establishment of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) can increase electricity demand in rural areas. For instance, an important energy need is identified in crop processing activities which represent an important output of energy appliances in areas where agriculture remains the major economic activity. Food storage and processing, manufacturing and other traditional men‑owned enterprises (MOEs) such as welding and carpentry, could easily be accessible for women with energy access.

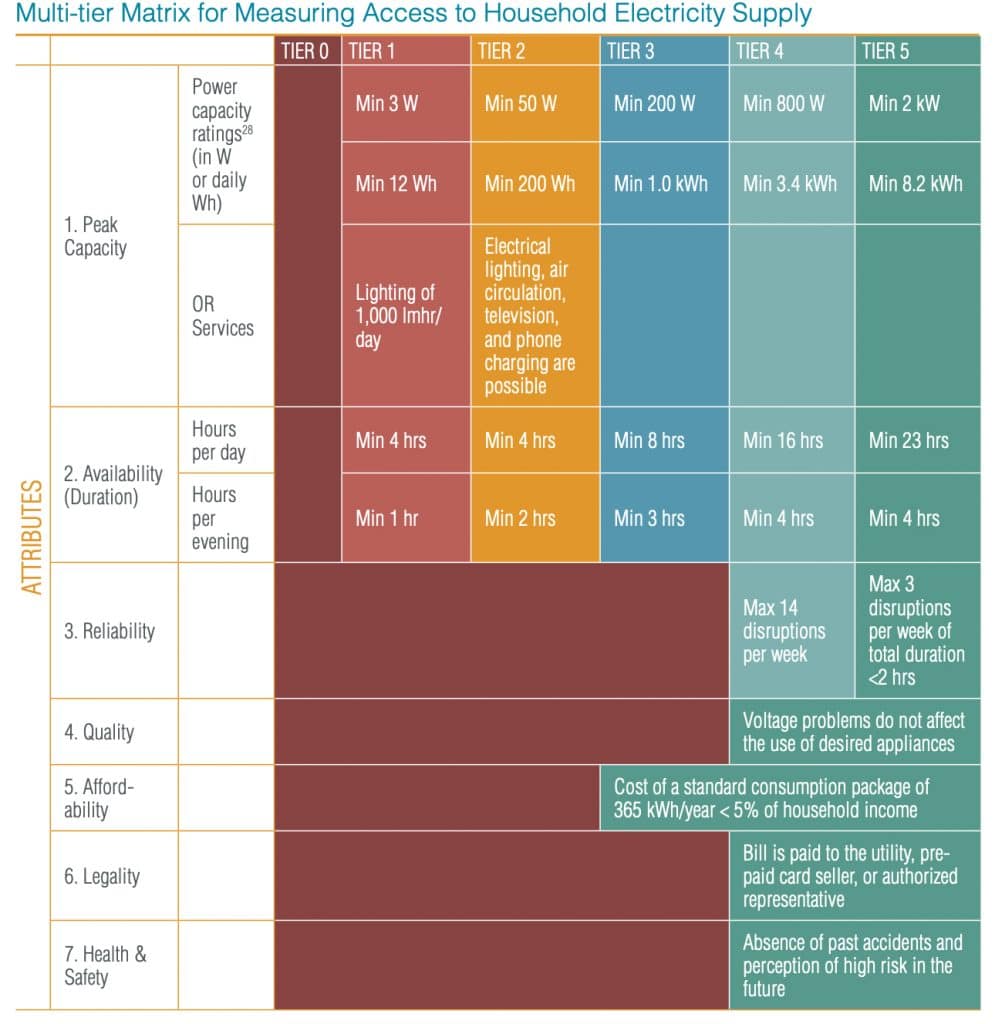

Meanwhile, the type of business activity relies on the type of electricity supply: the purchase of medium-load appliances (200–799 W) related to cold storage (fridges, freezers), manufacturing (electrical sewing machines) and food processing (blenders and electrical cookstoves) belongs to Tier Three, which in the multi-tier framework (MTF) for measuring energy access (Cf.Table One), corresponds to at least eight hours of electricity per day available (including at least three hours per evening).

Other equipment such as grinding mills, electrical water pumps and welding machines require a higher installed capacity than solar systems; these kinds of activities could be supported only by micro-grid systems.

Yet, the gap is far to be filled even once energy access is achieved. According to A. Pueyo, based on an analysis of PUE interventions, MOEs benefit more than women-owned enterprises (WOEs). This happens despite the fact that the WOEs have a higher “revenue multiplier” than men led enterprises as “women are known to spend, save and invest money in ways different from men” since “they prioritize spending on their families.”

Moreover, women can play a significant role for scaling up energy transition in rural contexts by selling energy services as they are “in a unique position to connect with their peers, increase awareness and deliver energy products and services.”

The upfront cost for getting a connection and buying equipment, less access to productivity-enhancing resources as seeds and collateral and (more in general) access to credit, remain the major bottlenecks for developing an energy-related business.

An enabling environment for scaling energy transitions

A holistic approach from private, civil society to the public sphere is required for mainstreaming gender in electrification programs and to take the complementary measures required for achieving a gender-sensitive approach in the renewable energy sector.

The Structural and Environmental Analysis (SEA) Framework identifies four levels of analysis: individual (personal attitudes), environmental (socio-economic environment), structural (national level) and super-structural (international community and organizations).

This approach, first conceived by USAID for HIV response international aid programs, has been recently applied by the Global Women’s Network for the Energy Transition (GWNET) to cope with major barriers to women participation in the energy sector.

Likewise, some “multi-level contextualised behaviour change strategies” can be identified in the energy access area.

At the individual realm, achieving time sovereignty for female workers is crucial for entering and remaining in the labour force.

From the environmental level, tailoring financing mechanisms to women’s specific situations as linking women entrepreneurs with reliable local financing institutions (LFIs) is pivotal for accessing leverage capital to kick off business activities. Community-saving groups as table banking can be more effective within rural areas as women have poorer access to productive resources such as land.

At this concern, development of women’s business activities could fill the gender gaps coming from limited land ownership and thus transform social gender norms.

Supporting activities like financial literacy and capacity building and training addressing entrepreneurship skills in sales and marketing and financial and business management needs to be implemented for successful empowerment programs.

At the structural stage, specific mandates for addressing gender issues in electrification programs is recommended: integrating a gender approach to electricity design programs, for instance collecting sex-disaggregated data and indicators, remains a national prerogative.

Rural energy agencies are working to address this issue and several institutions and intra-national cooperation initiatives as the ECOWAS Programme on Gender Mainstreaming in Energy Access (ECOW-GEN) work as facilitators in addressing gender imbalance in delivering energy services.

Meanwhile, the focus at this scale remains largely on grid-connected systems. For decentralised systems, rural energy services companies are the most suitable actor for addressing such issues.

Intangible resources such as access to broader and more independent information and social networks facilitate the establishment of an enabling environment that mainstreams gender approaches. Building an encouraging, safe and reliable network of women entrepreneurs in the energy sector could be a viable solution for accompanying female empowerment.

Civil society organizations play a central role in connecting potential beneficiaries to financing programs, social networks and vocational training promoting PUE within remote communities at the super-structural level.

Numerous initiatives address this issue: the sisterhood principle set by the “Solar Sisters” is a virtuous example of putting women at the core of the energy transition relying on mutual assistance within the members of the group giving support, assistance and providing products in case of shortage inventory.

The People-Centered Accelerator Mentoring Programme for Women in Energy Access sponsored by GWNET also aims to accompany women careers in the energy access sector.

Among others, the Lights on Women initiative and its platform, as well as the scholarship program sponsored by the Florence School of Regulation, is fully in line with such ambitious objectives.

A conducive change could occur only if all the four stages of analysis (individual, environmental, structural and superstructural) engage in the same direction. The call for an enabling environment shift from a male-dominated perspective in the energy sector to a gender-sensitive approach is urgent for scaling up energy transition in rural communities and beyond.

About Rita Chiara Mele

Rita Chiara Mele holds a Master’s Degree in Energy economics from IFP School in France (ENSPM — École Nationale Supérieure du Pétrole et des Moteurs) and in Sustainable Development, Geopolitics of Resources and Arctic Studies from Società Italiana per l’Organizzazione Internazionale (SIOI) in Italy.

Rita Chiara Mele holds a Master’s Degree in Energy economics from IFP School in France (ENSPM — École Nationale Supérieure du Pétrole et des Moteurs) and in Sustainable Development, Geopolitics of Resources and Arctic Studies from Società Italiana per l’Organizzazione Internazionale (SIOI) in Italy.

She previously worked for the Italian NGO CEFA supporting and collaborating on research activities on socio-economic outcomes of rural electrification project in Matembwe, Tanzania. Prior to CEFA, Rita Chiara worked at the Directorate of Financial Affairs of the French Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition and at Regulatory Affairs in the energy private sector.

Italian native based in France, she speaks Italian, French, English and Spanish, and is learning Arabic and Swahili. She actively volunteers with NGOs and organisations in France, Morocco and Italy to support female empowerment and unaccompanied minors through language inclusion initiatives.

Rita Chiara was also a recipient of the 1st Lights on Women scholarship in 2019.

Get in touch with Rita Chiara on LinkedIn!

The call for the 2nd Lights on Women Scholarship is now open!

FSR is offering four scholarships to women pioneering innovative energy solutions, research and initiatives that accelerate the energy transition.

REFERENCES

Bhatia, M., Angelou, N. (2015), Beyond Connections: Energy Access Redefined. ESMAP Technical Report; 008/15. World Bank, Washington,DC.

Cecelski, E. (2000), Enabling Equitable Access To Rural Electrification: Current Thinking And Major Activities In Energy, Poverty And Gender.

Danielsen, K. (2012), Gender Equality, Women’s Rights and Access to Energy Services: an Inspiration Paper in the Run-up to Rio+20, Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Dutta, S. (2015), Women, Energy and Economic Empowerment, Boiling Point 66, Chislehurst, United Kingdom.

Dutta, S. (2018), Supporting Last-Mile Women Energy Entrepreneurs: What Works and What Does Not. The Hague, Netherlands: International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy (ENERGIA).

ESMAP, World Bank (2013), Integrating Gender Considerations into Energy Operations, Knowledge Series 014/13.

Ferrant, G., Pesando L.M., Nowacka, K. (2014), Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes, OECD Development Centre, December 2014.

GIZ (2011), Productive Use of Energy – PRODUSE a Manual for Electrification Practitioners, GIZ, Eschborn.

GWNET (2019), Women for Sustainable Energy: Strategies to Foster Women’s Talent for Transformational Change.

IEA (2019), World Energy Outlook 2019, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2019.

IEA, IRENA, UNSD, WB, WHO (2019), Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report 2019, Washington DC.

IRENA (2019), Renewable Energy: A Gender Perspective, IRENA, Abu Dhabi.

Kapadia, K. (2004), Productive uses of renewable energy. A Review of Four Bank-GEF Projects. Consultant Report to World Bank.

Osunmuyiwaa, O., Ahlborg, H. (2019), Inclusiveness by design? Reviewing sustainable electricity access and entrepreneurship from a gender perspective, Energy Research and Social Science 53, 145-158 p.

Padam, G., Rysankova, D., Portale, E., Bonsuk Koo, B., Keller, S. and Fleurantin, G. (2018), Ethiopia Beyond Connections: Energy Access Diagnostic Report Based on the Multi-Tier Framework, Washington DC.

Pueyo, A. (2019), A Gender Approach to the Promotion of Productive Uses of Electricity, IDS Policy Briefing 162, IDS, Brighton.

Practical Action (2019), Poor people’s energy outlook 2019, Practical Action Publishing, Rugby.

UNEP (2017), Atlas of Africa Energy Resources. UNEP, Nairobi.