All eyes on gas storage

This is the 4th instalment of the Topic of the Month: Reacting to the new energy landscape

Underground gas storage (UGS) traditionally plays an important role in guaranteeing the security of supply and flexibility of the European gas system. Storages are typically refilled with gas in the summer, when prices tend to be lower, and emptied during the coldest months of the year, to cover peak demand.

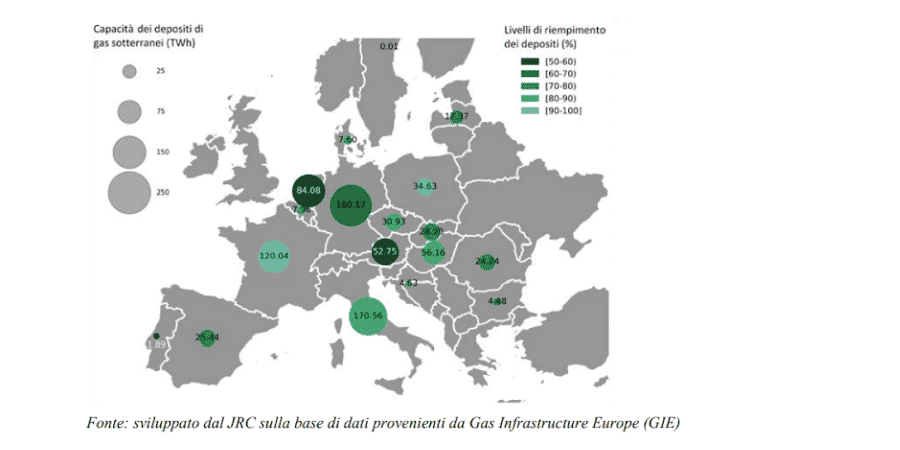

The EU-27 gas storage capacity amounts to 1147 TWh across 18 Member States[1] – approximately 100 bcm, or one-fourth of the total EU yearly gas demand. However, gas storage in Europe is unevenly distributed: some Member States (MS) have large storage sites, others only small ones and there are even many countries in Europe which do not host any storage facilities. Besides, there are significant variations across MS regarding the typology of UGS, ownership, and how storage is managed and regulated.

Gas storage trends since autumn 2021

Throughout the current energy crisis, and even more after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, gas storage has attracted attention as one of the instruments which could help mitigate the impact of the energy crisis.

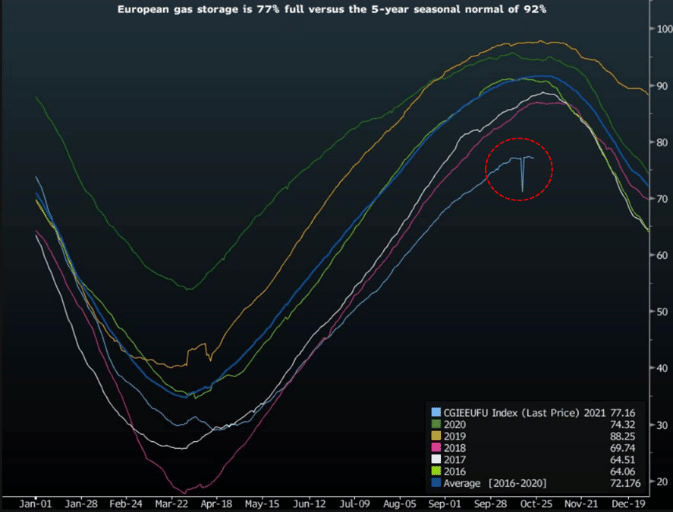

When the energy crisis started, at the end of summer 2021, gas storage levels in Europe were way below the 5-year average (see graph below). More gas than usual had been used during the spring and summer because gas demand had risen sharply than expected (due to economic, weather-driven factors and other more structural reasons).[2]

At the same time, re-filling levels were quite heterogeneous; notably, countries with a strictly regulated regime for storage had a higher filling level of their sites, as visible in Figure 2.

These considerations, jointly with the fear of rising gas prices and the ghost of a real scarcity of supply, attracted policy makers’ attention towards gas storage as a potential guarantee for security of gas supply and at the same time as a price catalyzer against the crisis.

Recent EU regulatory initiatives on storage

In October 2021, the Commission published a “Toolbox” listing the possible short-term and long-term instruments that could help mitigate Europe’s rising energy prices. Energy storage maximization was suggested among the “long-term measures” included in the Commission’s document, which also promised a reform of the EU Gas Security of Supply Regulation.[3]

Later on, in December, the publication of the Hydrogen and Decarbonised gas markets package included the recast of the Security of Supply (SoS) Regulation, introducing (art.7b) the possibility of:

- obliging gas storage users to store minimum UGS volumes

- incentivising gas storage bookings via tendering or auctions

- obliging TSOs to manage strategic gas stocks

- integrating storage into the TSO network.

The RePowerEU action plan published on 8th March 2022, which shifted the main policy target towards an urgent reduction of the EU’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels, also addresses gas storage. In particular, the Commission’s plan included a legislative proposal by April with minimum filling obligations; suggested that the existing solidarity arrangements in place for pipeline gas be applied to storage; listed a series of possible incentives (among which the contracts for difference) and introduced for the first time the idea of an EU coordinated storage platform.

Finally, in March, the EU Commission also delivered the promise of a new security of supply strategy by publishing the amendments to Regulation 2017/1938 (SoS) and Gas Regulation 715/2009.

The amendments, particularly at Articles 6a-6d, set up a minimum mandatory filling target of 90% for EU gas storage, to be achieved by 1 November each year (80% for 2022) as well as filling trajectories connecting intermediary filling targets (both to be adjusted as of 2023). In this context, Member States have the freedom to choose by which instrument and on which market participants impose this obligation: gas suppliers, storage owners, TSOs (purchasing strategic stocks) or via the new platform for joint purchase (see later). A burden-sharing mechanism is introduced, to ensure that all Member States equally share costs and benefits deriving from this new mechanism, which the EU Gas Coordination Group[4] is tasked and empowered to monitor closely.

Last but not least, article 3 in the revised SoS regulation imposes the mandatory certification of SSO, including those controlled by the TSO (already certified) and article 13 very importantly introduces a 100% discount on capacity-based transmission tariffs at storage entry and exit points.

On 27 June 2022, the proposed measures were adopted in a new Gas Storage Regulation. Under the new legislation, gas storage facilities will be considered critical infrastructure.

With these measures, the Commission expects in the first place to facilitate the refilling of gas storage in the EU, which was indeed and still is today, the crucial target to be reached ahead of next winter. However, several doubts have been raised about these measures’ effectiveness and their compatibility with the current situation of extreme uncertainty and the consequent high volatility of gas prices.

One of the key elements of the new approach to gas storage is the definition and the effective functioning of a “burden sharing mechanism” which could ensure that all MS contribute to and benefit from the refilling of gas storage on equal footing.

In the revised Regulation on Security of gas Supply, published on 23rd March, article 6c is dedicated to burden-sharing. The EU Commission encourages MS without storage facilities to “jointly develop a burden sharing mechanism with one or more MS with storage facilities” which should consider: the cost of refilling storage, gas volumes covering protected customers’ demand and any technical limitations linked to the availability of storage and withdrawal rates. A quite limiting and prescriptive approach, then, which imposes close monitoring of physical gas flows in case an emergency occurs.

Our proposal: ensure full storage capacity with a market-based mechanism

The Florence School of Regulation contributed to this debate with an alternative proposal for reforming gas storage by tackling it from an EU-level perspective.

In our Policy Brief, co-authored with DFC Economics colleagues, we generally agree on the idea of introducing storage filling obligations, but we also recommend that a target storage filling level is achieved and maintained with the smallest possible impact on the functioning of the internal gas market.

To this aim, we proposed a model based on a simultaneous multi-round auction, where volumes are set either at the EU or MS level and supported by pre-arranged solidarity agreements covering, in case of emergency, the destination of the gas to be supplied. The obligation would fall on shippers, rather than SSOs, and shippers would maintain the ownership of the stored gas. The auction would simultaneously allocate storage capacity in different market areas so that market participants could reveal their preferences related to the geographical location of the stored gas.

In practice, the auction would allocate storage obligations entailing:

- a certain gas capacity for a given thermal year,

- for a given entry-exit area, and

- with pre-defined filling level obligations at selected points in time.

Secondary trading would be allowed, as the winning participants in the auction could fulfil their obligations with gas stored by a different party in the same e-e (Entry-Exit) area.

Notably, auction participants would be allowed to bid at negative prices, if they expect the winter-summer gas price spread below the cost of storing gas. In such an unprecedented time of uncertainty, it could be envisaged that additional payment to/from the party awarded a storage obligation is assessed ex-post and equal to the actual difference between winter-summer price benchmarks, based on a standard injection/withdrawal time profile. This would effectively remove price risk, without altering the incentives of shippers.

We believe that our proposed model provides the following advantages compared to other proposals currently on the table:

- It is a market-based mechanism, known to the market and therefore eas(ier) to implement and at a relatively low cost;

- It builds on pre-existing mechanisms and actors (i.e., capacity auctions platform) hence allowing a speedy implementation compared to setting up new platforms/processes and their regulation from scratch;

- Easy monitoring of compliance as it allows for early detection of any missing injection, which could be replaced with UIOLI (Use it or lose it) provisions in a short time;

- Last but not least, it is a very flexible mechanism which allows for additional objectives or further constraints (for instance on the origin of the gas imported into Europe).

We believe that the successful implementation of such a mechanism would be able to deliver on the two pursued key targets of 1) improving EU gas security of supply and 2) reducing wholesale gas prices across Europe, hence bringing concrete improvement to the functioning of EU gas markets under the current and future emergency conditions.

Notes

[1] ACER and CEER views on the proposal for a regulation amending Regulations (EU)2017/1938 and (EC) 715/2009 relating to the access to gas storage facilities, 29 April 2022 available here

[2] For more information, see FSR resources: events highlights and recordings

[3] Regulation (EU) 2017/1938 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2017 concerning measures to safeguard the security of gas supply and repealing Regulation (EU) No 994/2010 available here

[4] The Gas Coordination Group was created in 2006 according to Directive 2004/67. Chaired by the European Commission, it is composed of gas competent representatives of the Member States, the European organisations of the gas sector and consumers.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights