Methane Emissions

What are methane emissions and why do they matter? And what is the EU framework to abate them? FSR answers all the burning questions in this cover the basics article.

Methane is a short-lived, but potent greenhouse gas, which causes 25% of anthropogenic warming experienced today, yet compared to CO2 it has received relatively little attention. The mitigation of methane emissions will play a vital role in achieving the Paris Agreement objective of holding global temperature increase to 2-1.5 °C by mid-century. In the EU context, the reduction of methane emissions will contribute to meeting both the 2030 GHG reduction target by 55% compared to 1990 levels, and the European Green Deal objective to reach climate neutrality by 2050.

In this Section, we explain what methane emissions are, why they matter and how they could be reduced.

What are methane emissions and why do they matter?

Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO2). In comparison to CO2, methane remains in the atmosphere for a shorter time (around 10-12 years) but it is a much more potent greenhouse gas (GHG), as it attracts more heat per unit of mass than CO2.

One way to compare the environmental impact of the two gases is by their Global Warming Potential (GWP) which, in this case, is a measurement of the heat absorbed by 1 tonne of methane over a given period of time, proportionate to the emissions of 1 tonne of CO2 greenhouse. Therefore, the GWP of CO2 is always 1, while the GWP of methane is calculated as 84 in a 20-year perspective and 28 in a 100-year perspective, according to the IPCC AR5. In the latest IPCC AR6, GWPs for methane have been revised downwards: 82.5-80.8 [fossil methane-non-fossil methane] in a 20-year perspective and 29.8-27.2 [fossil methane-non-fossil methane] in a 100-year perspective. This change is a result of the revised estimates of methane lifetime and its indirect chemical effects (the inclusion of carbon-cycle response for non-CO2 gases).

Seeing the high heat-trapping potential of the gas, the abatement of methane emissions would have an immediate effect on climate. Hence, reducing methane emissions is important to keep the Paris Agreement 1.5 °C target within reach. Emissions decrease would also benefit air quality, as methane contributes to the formation of ground-level ozone – an air pollutant1.

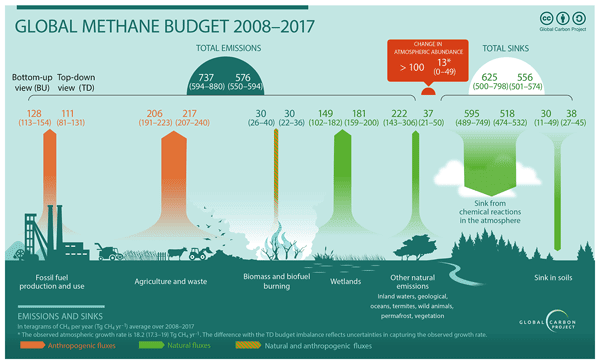

The Global Methane Budget provides an estimate of atmospheric sources and sinks of methane over the period 2008 – 2017. While the net change is well understood (13 Mt), there is more uncertainty regarding individual sources and sinks.

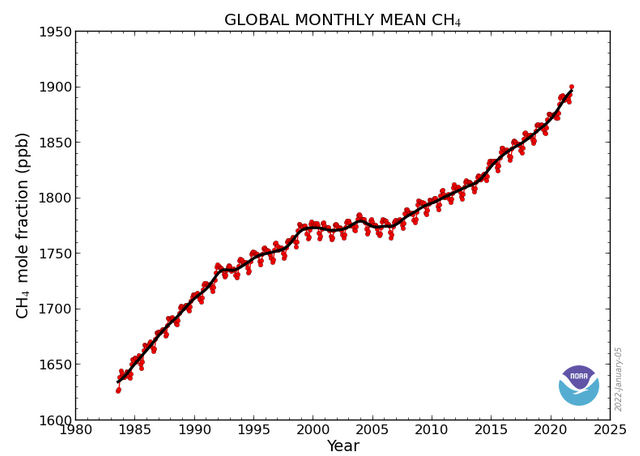

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is increasing and is approximately 2.6 higher than pre-industrial levels (1750). Methane concentration in the atmosphere surpassed 1900 ppb in 2021 and the increase is mostly driven by emissions from agriculture and fossil fuel use.

What are the main sources of methane emissions?

The Global Methane Budget shows that the annual global methane emissions are around 737-576 million tonnes (Mt), the majority of which (nearly 60%) is the result of human activity. These emissions originate mostly in agriculture (40%), the energy (35%) and the waste sectors (20%)2.

Agriculture is responsible for contributing the largest amount of human activity related emissions, both globally and at the EU level. Farm-related emissions primarily come from enteric fermentation (fermentation within the digestive systems of animals), manure management and rice cultivation. The energy sector follows closely in terms of emissions. Methane is mainly emitted during the extraction, transport, distribution and use of fossil fuels (oil, gas and coal). Finally, in the waste sector, landfills (organic waste, landfill gas) and, to a lesser degree, wastewater treatment are the major sources of emissions.

What is the role of methane emissions in the oil and gas sector?

As mentioned before, energy-related methane emissions – although lower than those coming from agriculture – are considerable in size. Specifically, the oil and gas sector accounts for 63% of the total methane emissions from fossil fuels (coal mining accounts for 33%; other industries (metals, chemical), fossil fuel fires (e.g. Kuwait oil and gas fires), and transport constitute the remaining 4%).

There are three types of methane emissions from the oil and gas sector – fugitive, venting and flaring emissions – which pose different challenges in terms of measurement and abatement. Fugitive emissions are unintentional releases of methane (e.g. resulting from wear and tear in the instruments). Since it is difficult to predict when and where the releases can happen, the operators do regular inspections at their facilities to detect and fix the leaks.

Venting is an intentional release of methane, which can for instance be due to safety reasons. In principle, we know when, where and how much is emitted, but in some cases the equipment vents more than it supposed to do. In order to reduce venting emissions the operators can replace high-bleeding pneumatic devices with low-bleed pneumatic devices, install new devices such as vapour recovery units or flare the excess methane instead. In some cases (e.g. lack of offtake infrastructure) methane is combusted in flares and transformed into CO2. In many cases, however, not all methane is burnt and some of it is released as unburnt gas: that is a methane slip.

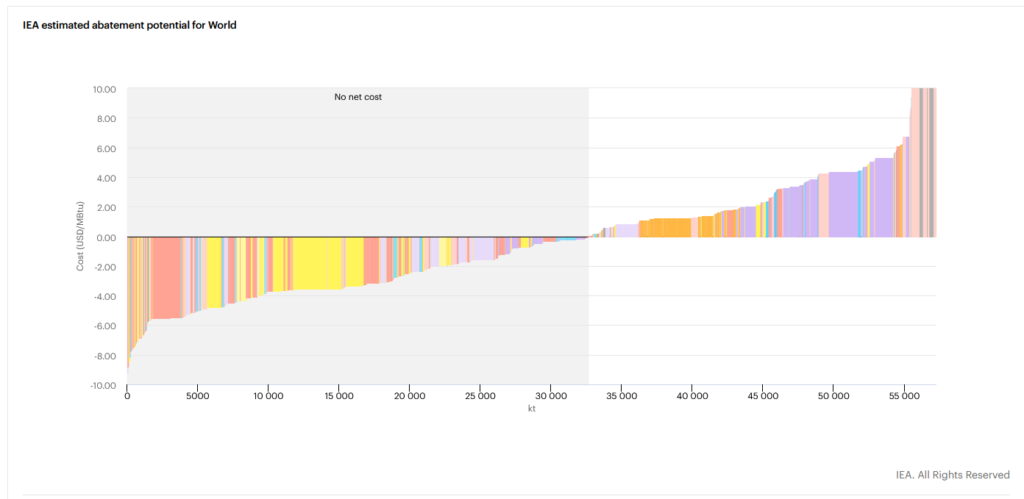

The size of the phenomenon begs the question: what can we do about it? For one thing, a large part of fossil fuel emissions can be reduced cost-effectively with the use of existing abatement technologies. Moreover, unlike CO2, methane has commercial value in itself – as it is the main component of natural gas – so efforts to capture methane can often be monetised as shown in Fig.33. Hence, the role gas will play in the transition to a carbon-neutral energy system is heavily dependent on the industry’s ability to reduce methane emissions.

Unabated methane emissions in the sector have, in fact, the potential to question the environmental benefits of switching from oil and coal to natural gas or blue hydrogen altogether.

Even in future low-carbon energy systems, where fossil gas will be replaced by renewable and low-carbon gases (biogas, biomethane and blue hydrogen), the issue of methane emissions is likely to persist, according to the recently published EU Hydrogen strategy.

What measures is the EU oil and gas sector undertaking to reduce methane emissions?

Currently, most actions to reduce methane emissions in the EU oil and gas sectors are voluntary. Here, we cover three important industry initiatives.

First, the group of companies led by Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE) and Marcogaz compiled a report investigating potential ways in which the industry can contribute to the reduction of methane emissions. This publication, constituting a one-of-a-kind summary of industry initiatives to tackle methane emissions, was presented and discussed at the Madrid Gas Regulatory Forum in 20194.

Second, over 70 companies joined the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) 2.0 Reporting Framework. The companies participating in this initiative will voluntarily report emissions from their facilities annually, according to a standardised methodology focused on emissions measurement. The aggregated data will be made publicly available.

Third, the Methane Guiding Principles initiative is organising training to raise awareness about the issue of methane emissions among the oil and gas companies, is sharing best practices and advocating policies and regulations to address methane emissions5.

What is the Global Methane Pledge?

It is a joint EU-US initiative with a collective goal to reduce man-made methane emissions by 2030 by at least 30%, compared to 2020 levels. The Pledge was launched at the margins of COP26 climate negotiations in Glasgow in 2021. Over 100 countries supporting this initiative also committed to improve the methane quantification methodologies used in their inventories, especially from high emission sources. Together they account for nearly half of anthropogenic methane.

Although the Pledge is not a part of the negotiation mandate at COP26, this initiative together with the publication of the IPCC report in early 2022 helped to focus the attention on methane and its short-term impact on climate. However, the effectiveness of such initiative is undermined by the absence of some of the major methane-producing countries (Australia, China, India and Russia) and of formal mechanism to track the progress towards meeting Global Methane Pledge.

What is the EU framework to reduce methane emissions?

The EU methane strategy and the proposal for the EU methane regulation are currently the most important elements of the EU policy framework on methane emissions. The European Commission presented the EU strategy to reduce methane emissions on 14 October 2020, that is 24 years after the publication of the first EU Methane strategy in 1996. The 1996 strategy helped to reduce methane emissions in the EU yet was not a complete success.

The 2020 strategy covers all sources of emissions – agriculture, waste and energy (including emissions related to the biogas and biomethane production and use) and sets the objective to reduce EU methane emissions by 35-37% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. The strategy combines cross-sector and sector-specific actions, and sets a clear priority – robust methane emissions measurement and reporting – with a role for corporate reporting (based on voluntary initiatives such as the OGMP2.0), satellite observations (Copernicus Programme), and the establishment of an International Methane Emissions Observatory.

The strategy specifies actions targeting emissions from agriculture and waste sectors, which currently account for 53% and 26% of all man-made methane emissions in the EU. The actions include: 1) better emissions measurement and quantification (i.e. analysis of life-cycle methane emissions metrics in agriculture, and enhanced MRV in the waste sector), 2) mitigation (e.g. by the provision of assistance to Member States in tackling unlawful practices and providing technical assistance to address substandard landfills, biodegradable waste treatment or through the review of the Landfill Directive in 2024); 3) research activities financed through Horizon Europe 2021-2024 program.

Another important aspect is the external dimension of the strategy. Being one of the major natural gas importers in the world, the EU has both responsibility and leverage to advocate for the reduction of energy-related methane emissions globally. According to some estimates, the methane emissions from the imported natural gas are 3-8 times higher than the methane emissions within the EU borders. The strategy suggests the following actions: 1) the creation of International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO) tasked with the development of the Methane Supply Index (index demonstrating methane footprint of imported gas); 2) satellite data sharing on super-emitters; 3) cooperation with energy buyers and suppliers (North America, China, South Korea, Japan) and 4) cooperation through multilateral fora and institutions such as: World Bank, United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), International Energy Agency (IEA), the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC).

The European Commission presented a proposal for a regulation on methane emissions reduction in the energy sector on 15 December 2021, as part of the hydrogen and gas decarbonization package. The proposal introduces new requirements in terms of measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) of emissions, as well as abatement measures including regular leak detection and repair (LDAR) and restrictions on venting and flaring. The regulation also puts forward rules to increase transparency on methane emissions associated with fossil fuels imports and the creation of publicly available methane transparency database (art. 28) and methane emitters global monitoring tool (art. 29).

The proposal targets the emissions arising along the entire value chain (with the exception of end-use and biogas production), including monitoring obligations concerning emissions from inactive wells, as well as closed and abandoned coalmines. The proposal will now be proceeded by the European Parliament (ENVI Committee) and the Council through ordinary legislative procedure. It is likely that the final version of the regulation may be adopted in mid-2023.

What are other regions doing to reduce methane emissions?

Over the course of the last few years, more and more jurisdictions have been adopting methane policies and setting methane reduction targets. North America has been one of the most dynamic regions in this respect.

In 2016, the US, Canada and Mexico set up a joint objective to reduce methane emissions in the oil and gas sector by 40-45%- from 2012 levels – by 2025, and all of them have already adopted methane-specific regulations to achieve this target. It should be noted that the US federal regulations on methane adopted in 2016 have been rolled back in 2020, yet methane emissions in the oil and gas sector are regulated in several US states including Colorado, Pennsylvania, and North Dakota. The US Environment Protection Agency proposed new regulations in 2021.

The major EU natural gas suppliers – Norway and Russia – use economic instruments to reduce methane emissions in the oil and gas sector. In Norway, each tonne of methane released in the air during oil and gas production is taxed, while in Russia an environmental charge on methane release is applied. The Canadian province of Quebec and the state of California included methane emissions in their cap-and-trade programs.

If you still have questions or doubt about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Relevant links

Policy Briefs:

- “Satellite and other aerial measurements: a step-change in methane emission reduction?” by M. Olczak, A. Piebalgs and Ch, Jones

- Energy security meets the circular economy : a stronger case for sustainable biomethane production in the EU

- Designing an EU methane performance standard for natural gas (English and Chinese versions)

- Methane emissions from the coal sector during coal phase-out

Webinars:

- How to establish a right baseline for rigid methane mitigation policies

- Is the EU ready for new methane legislation?

- Hard to measure: how can we improve monitoring of methane emissions?

Interviews:

- New EU methane regulation explained

- The EU Methane Strategy and its impact on natural gas suppliers

- OGMP 2.0 and International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO) explained

Topic of the Month:

Courses:

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights