Crisis as a Challenge for the EU’s Treaty Framework for Energy Security

This is the first instalment of the Topic of the Month: Building Energy Security in Times of Uncertainty

The May 2023 Topic of the Month blog posts series examines the steps taken in law and policy to enhance energy security in the European Union. The February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought this issue to the forefront of policymakers’ minds in Europe. Accordingly, recent FSR research[i] [ii] and discussions with experts[iii] [iv] at the School have examined the measures proposed and adopted by the EU as part of its REPowerEU Plan of May 2022,[v] particularly as they pertain to natural gas imports.

In this series of blogposts, we hope to complement this research by offering a better understanding of the systemic constraints that such security-of-supply measures face in the European Union. This first instalment looks at the legal and institutional setup for the making of energy security measures in the EU.

Energy Security in the European Union

Guaranteeing security of supply is a particularly difficult task to achieve in a multilevel system such as the EU. On the one hand, the level of both physical and regulatory integration of Member States’ energy systems means that a security-of-supply shock in one Member State is bound to have knock-on effects on other Member States. This seems to make legal and institutional arrangements at the European level for the guarantee of such security an imperative. However, the EU also needs to take into account considerable geographical, economic, and political differences between Member States when taking such measures. It further needs to operate within the bounds of the legal competence conferred upon the Union by its foundational treaties.

For many years, in the absence of a formal energy competence in the Treaties, the EU has in the past sought to guarantee energy security by primarily relying on its internal market competence. Since the Treaty of Lisbon, the Union has formal, shared competence to pursue the objectives of a common energy policy, one element of which is specified as ensuring security of energy supply in the Union.[vi] The objectives of the Union’s energy policy should further be pursued “in a spirit of solidairty between Member States”, a provision that was reportedly inserted into the language of the Treaty following calls from Member States concerned about energy security after the 2005/2006 Ukraine-Russia gas dispute. This solidarity in the pursuit of common European energy objectives, however, needs to be balanced against the right of Member States to determine “the general structure” of their energy supply as stipulated in the same Treaty article.

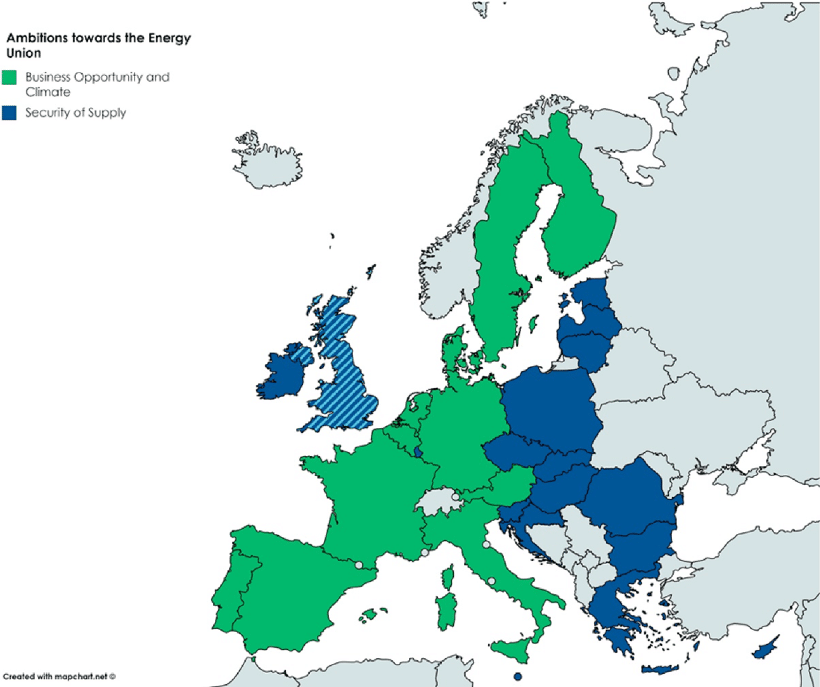

This tension between the need to achieve common objectives without being able to directly prescribe Member States’ energy mix in the name of energy security has posed a challenge to the development of a coherent body of security law and policy in the EU. Further, the Union has in the past sometimes struggled to manage the relationship between the objective of energy security on the one hand, and that of decarbonisation of the energy sector on the other. Here, Member States have tended to have rather clear and rigid preferences, which proved difficult to bring into dialogue at the European level. To some degree, this can be seen in the development of the European Energy Union, whose Clean Energy for All Europeans legislative package significantly shaped contemporary European energy law. The Energy Union, in fact, started as a proposal to enhance energy security. This security-centric idea of the Energy Union was proposed in a 2014 Financial Times Op-ed by Donald Tusk, then Prime Minister of Poland. Writing in the aftermath of the Russian annexation of Crimea, Tusk began his call for a European Energy Union by stating that “[r]egardless of how the stand-off over Ukraine develops, one lesson is clear: excessive dependence on Russian energy makes Europe weak. And Russia does not sell its resources cheap – at least, not to everyone”.[vii] Yet Member States valued energy security in the Energy Union very differently. According to 2019 research investigating Member States’ energy priorities,[viii] States at the periphery of the Union tended to strongly prefer an energy security focus while Member States located further West in the Union tended to prioritise climate action. The arrival of the European Green Deal did not fundamentally change this outlook.

REPowerEU: Transformative or Temporary?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the EU’s response, REPowerEU, have challenged this established political and legal context for energy security at the EU level. Firstly, and rather obviously, the crisis is a stress test for how well existing EU energy security measures are able to deal with a cessation of Russian fossil fuel imports. The spectre of a weaponisation of gas has been a driving force of primary and secondary EU energy security law. Now that this worst-case scenario has occurred, any faults of these preventive measures are likely to become more obvious. Secondly, the crisis has made it vastly more difficult for Member States to prioritise energy sector decarbonisation without regard for, or even at the expense of, overall EU energy security. The ambitious targets of the European Green Deal need to be pursued in synergy with the pursuit of strategic autonomy in the energy sphere. Thirdly, the crisis prompts questions as to whether the euroconstitutional balance between energy solidarity and energy sovereignty that has emerged over decades of integration is sufficient for the development of such a resilient and coherent body of energy security policy. The REPowerEU Plan has been pursued with impressive speed and with remarkable unity between Member States. It has resulted in measures that would have been unthinkable before February 2022. However, the temporary nature of most emergency measures adopted under the Plan[ix] means that the lasting impact on the conditions under which energy security law and policy are made in Europe remains to be seen.

[i] James Kneebone, “Gas: A History of Energy Security in the EU. And What’s next Post-Russia?” (Energy Post, 14 February 2023) https://energypost.eu/gas-a-history-of-energy-security-in-the-eu-and-whats-next-post-russia/

[ii] Ilaria Conti and James Kneebone, ” First Look at REPowerEU: The European Commission’s Plan for Energy Independence from Russia” (Florence School of Regulation, 19 May 2022) https://fsr.eui.eu/first-look-at-repowereu-eu-commission-plan-for-energy-independence-from-russia.

[iii] Florence School of Regulation, “Gas Supply: How Has the Concept of Solidarity Evolved in the EU? – Interview with FSR Research Associate Marzia Sesini” (Florence School of Regulation, 1 February 2023) https://fsr.eui.eu/gas-supply-how-has-the-concept-of-solidarity-evolved-in-the-eu/

[iv] Florence School of Regulation, “Insights on Three Newly Introduced EU Emergency Gas Measures” (Florence School of Regulation, 4 April 2023) https://fsr.eui.eu/lessons-learned-from-the-crisis-insights-on-three-newly-introduced-eu-emergency-gas-measures/

[v] Commission, “REPowerEU Plan” COM(2022) 230 final https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A230%3AFIN

[vi] Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) art 194 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX%3A12008E194%3AEN%3AHTML

[vii] Donald Tusk, “A United Europe Can End Russia’s Energy Stranglehold” Financial Times (21 April 2014) https://www.ft.com/content/91508464-c661-11e3-ba0e-00144feabdc0

[viii] María de la Esperanza Mata Pérez, Daniel Scholten and Karen Smith Stegen, “The Multi-Speed Energy Transition in Europe: Opportunities and Challenges for EU Energy Security” (2019) 26 Energy Strategy Reviews 100415 https://www-sciencedirect-com.eui.idm.oclc.org/science/article/pii/S2211467X19301087

[ix] Leigh Hancher, “Solidarity on Solidarity Levies and a Choice of Energy Mix” (Verfassungsblog, 8 February 2023) https://verfassungsblog.de/solidarity-on-solidarity-levies-and-a-choice-of-energy-mix/; François-Charles Laprévote, “Article 122 TFEU as a Legal Basis for Energy Emergency” (Cleary Gottlieb, 9 November 2022) https://www.clearygottlieb.com//news-and-insights/publication-listing/article-122-tfeu-as-a-legal-basis-for-energy-emergency-measures

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights