Climate Change: What Duty for Regulators?

Highlights from the online debate: Regulatory responsibility and the duty of care in realising the energy transition

On Wednesday, 20 October 2021, the FSR hosted a debate examining the consequences of recent (successful) climate change litigation for regulators. In particular, the debate centred on the question of whether we can or should speak of a duty of care for national regulatory authorities.

What duty for regulators?

The debate was hosted by Prof. Alberto Pototschnig (FSR), who introduced the speakers and welcomed participants. He then handed over to Prof. Leigh Hancher (FSR). Prof. Hancher introduced the topic of the debate, stating that it is not easy to find clear rulings on the role of regulatory authorities. This is in spite of increasing numbers of climate change litigation, with approximately 1,800 such cases already having been filed worldwide as of July 2021. Within the body of climate change litigation, we can distinguish between cases brought against state actors, including – potentially – NRAs, and those brought against non-state actors, such as private companies. The most famous example of the former is the landmark Dutch Urgenda ruling, in which the court found that the Dutch government had a duty of care vis-à-vis its people and future generations and was thus compelled to take additional measures to comply with its energy and climate targets. It was also a Dutch court that recently found a duty of care to exist for Shell in a ruling that the company is currently appealing.

The Urgenda case, in particular, had a significant knock-on effect on other jurisdictions. However, there is variation in the legal claims made by applicants in such cases and in how far courts are prepared to go in their rulings. In Belgium, for example, an action was brough against both federal and regional authorities, alleging that the failure to take action on climate change was in breach of their duty of care, but also that such conduct was in breach of article 2 (right to life) and article 8 (right to private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). While finding against the state actors, the Belgian court did not order an increase of greenhouse gas reduction targets, citing separation-of-powers concerns. Meanwhile, a recent Swiss climate case that is now pending before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), in addition to breaches of articles 2 and 8 of the Convention, also alleges a breach of article 13 (right to an effective remedy) thereof. In the Shell case, on the other hand, the court found that the company had breached its duty of care under Dutch tort law and the case was also based on the fact that Shell had acted contrary to UN guiding principles, thus combining national and international law.

It is still unclear what this means for regulators. Under EU law, energy regulators are expected to be independent and the recently unveiled 'fit for 55' legislative package will introduce additional obligations on regulators to act in the public interest, which might expose them to new claims that they too have a duty of care. However, it has also been recognised by courts that it is important for regulators to balance the different interests at stake.

In the United Kingdom, for example, a court recently found that the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy had to balance the needs of citizens to have adequate energy infrastructure against decarbonisation priorities. With that, Prof. Hancher handed over to the other speakers, asking whether regulators need further guidance on how to exercise their duty of care, and if so, who should provide it (in the EU)?

Insights from the panel

The next speaker, Prof. Dr Henrik Bjornebye (University of Oslo and BAHR) spoke about the recent judgment of the Norwegian Supreme Court in the climate case of Greenpeace Nordic Ass’n v. Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Here, the environmental NGOs bringing the case alleged procedural errors relating to the award of petroleum production licenses and based their claims on the right to environment enshrined in section 112 of the Norwegian constitution, as well as the right to life and to respect private and family life, protected both under the constitution and the ECHR. While the Supreme Court ruled that the right to a clean environment was, in principle, a substantive right, it held that the threshold to reviewing and restricting government action on the basis of this right was very high. The court ruled that the government had acted within its competence in awarding the licenses and that its substantive assessment could thus not be overruled. This means that in Norway, as long as the government acts within its competences, it will be hard to challenge the substance of its resource management decisions. However, the legacy of the Greenpeace litigation may be a greater degree of scrutiny when it comes to procedural matters as well as more climate change litigation based on European or international human rights law.

After the conclusion of the opening presentations, Prof. Pototschnig introduced the panel, composed of Zsuzsanna Pató (Regulatory Assistance Project); Jorge Vasconcelos (FSR); and Will Webster (OGUK).

In her introductory remarks, Dr Pató shared her insights from the perspective of regulators and from that of Central and Eastern European countries. Dr Pató stated that a duty of care for regulators would be welcome for two reasons: first, because the Energy transition is currently in progress, with the potential for a lot of political turmoil, increasing the need for regulation to take a step back from politics. Second, Dr Pató emphasised that 2050, the target year for achieving EU carbon neutrality, is very close indeed relative to the changes that need to happen in the energy sector. This underlines the need for speedy regulatory change. Thus, the regulator should not be completely independent in that it still needs to be held accountable, but a situation in which the regulator just serves the wishes of government should also be avoided. Dr Pató discussed the idea of a minimum duty of care for regulators, which would oblige them to speak out to the public, parliament, and government whenever they think the measures taken are insufficient to achieve climate change targets. Such a requirement could potentially be operationalised through amendments to the statutes of regulators.

In Central and Eastern European countries, the EU, rather than national governments, is likely to provide the strongest incentive for decarbonisation. The EU could thus be seen as a strong ally for regulators wishing to push for more decarbonisation.

In Professor Vasconcelos’ opinion, national regulatory authorities could potentially be confronted with fundamental rights litigation similar to that we have seen against state and non-state actors. Such human rights litigation, however, is problematic from the point of view of citizens, since a high degree of legal abstraction is necessary to infer concrete guidelines for the regulator from the infringement of fundamental rights due to a lack of progress or ambition to achieve decarbonisation targets. Further, most regulators are not set up to pursue a rights-focused course of action. Very often, there is an interpretation of the regulator’s duties holding that the regulator should avoid public policy interference with regulatory action. However, there is a need to distinguish clearly between interference, which would consist of actors trying to influence a concrete decision, and regulators simply taking public policy into account. It would be difficult to argue that when a government agrees on a climate law it is trying to limit or interfere with the powers of the regulator.

In his intervention, Mr Webster highlighted how important regulators are for the way that European directives are implemented. Today, arguably, the most important function of regulators should be to promote investment in a way to deliver a net zero outcome. This is likely to require amendments to the framework for national regulatory authorities through directives, guidelines, or both. According to Mr Webster, particularly the mindset of prioritising cost reduction for the consumer might need to be changed. Increasingly, the speed of technology development and diffusion, as well as the need for rapid decarbonisation demand a mode of decision-making under conditions of uncertainty. Speaking from the perspective of the oil and gas sector, Mr Webster highlighted that until very recently, the UK Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) had a duty to maximise economic recovery. This was until February 2021, when the OGA was able to review its guidance and included a net-zero obligation, a specific requirement to reduce emissions. Mr Webster stated that the whole framework for regulators in the energy sector is evolving in national and EU legislation. Further, given the steady increase of climate litigation around the world, it is likely that the frameworks under which regulators operate will be the subject of increasingly close public and legal scrutiny.

The views of the audience

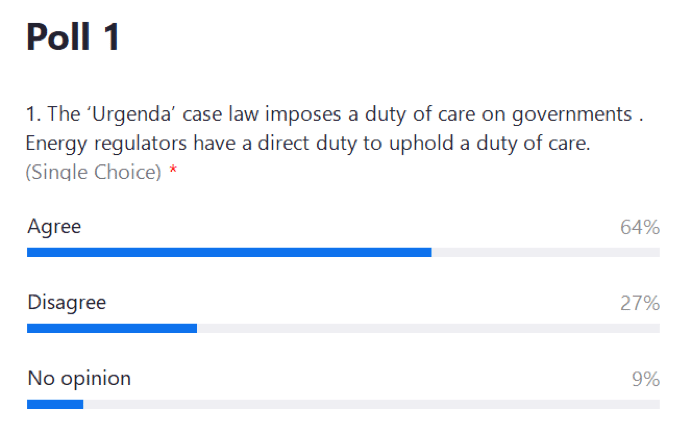

In an ensuing series of polls, participants were able to voice their opinion on the matter of regulators’ duty of care regarding climate change. The results of the polls largely concurred with the points made by the speakers. In Poll 1, a majority (64%) of participants agreed that regulators have a direct duty of care similar to that found to exist for the Dutch government in the Urgenda case.

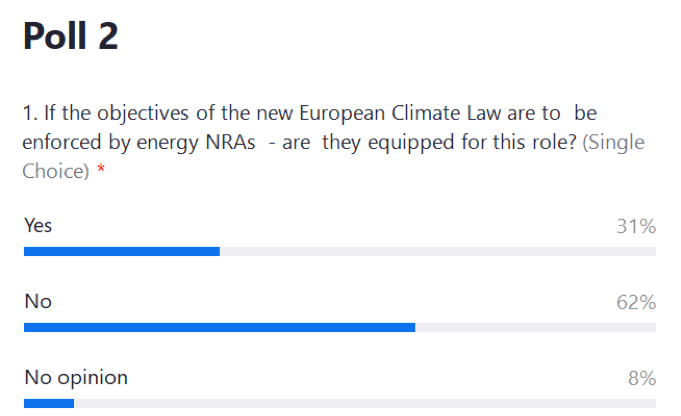

Poll 2, meanwhile, showed that most participants (62%) did not consider national regularoy authorities to be adequately equipped to act as enforcers of the European Climate Law.

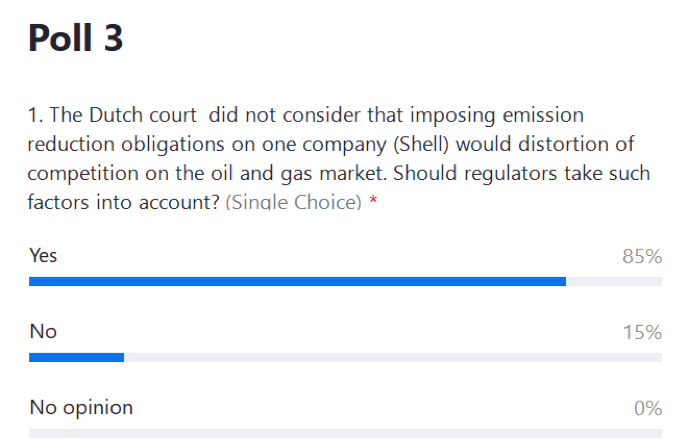

Finally, an overwhelming majority of participants (85%) thought that, given that in the Shell ruling the Dutch court imposed emissions reductions oblications on only a single private company, regulators would perhaps be better placed to make decisions of this kind, also taking into account the effects such obligations have on competition.

After a lively discussion of these results, Professors Hancher and Pototschnig thanked all speakers for a rich and stimulating debate. Concluding, Prof. Pototschnig stated that this debate touched on and ran parallel to the conversation regarding the extent to which government can give guidance to regulators. The question of whether national regulatory authorities had the competences and resources to exercise a duty of care is certain to be the subject of much future debate and analysis.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights