Carbon Markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement

What types of carbon markets exist? What is the Paris Agreement? Why is Article 6 so relevant?

In this article, we focus on carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. 2025 marks the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement, the 30th UNFCCC Conference of the Parties and the submission of the Nationally Determined Contributions 3.0 outlining countries’ climate action until 2035. Carbon markets under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement play a crucial role in the global climate protection efforts.

The Paris Agreement is the most comprehensive international treaty to limit global warming, and negotiations on its implementation continue under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). One important aspect of the agreement is included in Article 6, which incentivises countries to work together to achieve their national climate targets. The article provides the basis for international carbon markets under the Paris Agreement, involving bilateral and multilateral carbon trading (Article 6.2) and a centralised UN carbon market (Article 6.4). Finally, it encourages climate cooperation without credit transfers involved (Article 6.8). Almost one decade after its adoption, the operational principles of Article 6 have been negotiated, and parties are entering the implementation phase. The following blog post will explain the functioning of Article 6 carbon markets and examine the opportunities and challenges related to their implementation.

What types of carbon markets exist?

When referring to carbon markets, it is important to clarify the terms used, especially since more overlaps and connections are emerging between different types of markets (for an elaborate overview, see Policy Brief on the State-of-play in International Carbon Markets 2025). Generally, carbon markets describe markets in which carbon units (i.e., credits or allowances) are traded, each unit representing an amount of greenhouse gas emissions, usually 1 ton of CO2 equivalent. In allowance markets, such as the EU Emissions Trading System, covered entities, such as companies, are legally obliged to purchase and can trade pollution permits (allowances), and an overall limit on emissions (the so-called cap) is set. In contrast to this, in carbon credit markets, entities can purchase carbon credits from emission reductions or removals for different uses, mainly for voluntary climate pledges. Whereas allowance markets price emissions, credit markets award emission reductions or removals. There can be connections between these markets, for example, when covered entities in an emissions trading system (ETS) use carbon credits to lower their emissions, as is the case in the Indonesian and Korean ETSs. Moreover, a growing number of countries are setting up national schemes for carbon credit markets, which feature elements of both compliance and voluntary schemes.

While allowance markets are characterised by their compliance nature, carbon credit markets are more often voluntary. Only in compliance carbon markets, allowances, or carbon credits can be used to fulfil a legal obligation of the regulated entity, as part of an Emissions Trading System or under multilateral commitments, such as the CORSIA scheme for aviation, or State-level interactions under the Paris Agreement.

What is the Paris Agreement?

The goal of the Paris Agreement, signed in 2015, is to mitigate the severe impacts of climate change by keeping the increase in the global average temperature well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. The treaty obliges countries to submit their climate action plans, the so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), every five years since 2020. The plans, which are required to increase ambition over time, set near-term emission reduction targets and describe the planned climate mitigation and adaptation measures, while longer-term measures are summarised in each country’s Long-Term Strategy. The 2024 NDC synthesis report summarises that countries are increasingly counting on Article 6 in their NDCs, with 78 per cent indicating the use of at least one of its approaches.

Why is Article 6 so relevant?

Articles 6.2 and 6.4 are based on the principle that market-based international cooperation can significantly reduce the overall cost of climate change mitigation. Accordingly, emission reductions and removals should occur where it is least costly. This is, for instance, the case in countries with favourable preconditions for renewable energy and carbon sequestration projects, or where projects can target “low-hanging fruit”. Examples include wind power projects, the restoration of natural ecosystems, such as mangroves, grasslands and peatlands, projects improving water quality to avoid the boiling of water before use and projects that replace wood-fired cookstoves with sustainable alternatives. Countries that reduce more emissions than required for their own climate targets can convert the surplus into carbon credits and sell them to other countries seeking to meet their NDCs. This is based on the physical reality that greenhouse gases have no nationality and reductions or removals benefit all countries regardless of where they occur. Besides reducing the overall cost of mitigation, international carbon trading can create an economic incentive for climate action in middle and low-income countries financed by advanced economies, ideally contributing to sustainable development and creating co-benefits for local communities. Additionally, it might lead to more ambitious climate targets in countries where mitigation opportunities are scarce or very costly.

What is Article 6.2, and how does it work?

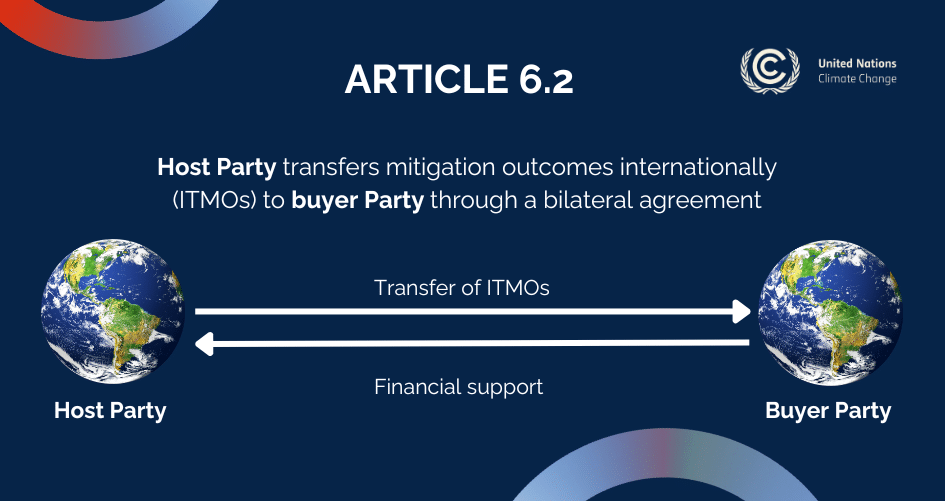

Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement establishes a cooperative framework that allows countries and private entities to cooperate directly (bilaterally) using so-called internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs). The article facilitates the international transfer of mitigation outcomes, meaning that a country or corporation can count emission reductions achieved in other countries towards its own climate targets under bilateral or plurilateral agreements. Once authorised by the host country, ITMOs can be used by countries to achieve their NDCs, by aircraft operators to offset their emissions in the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), and by private actors to offset their emissions in the voluntary carbon market (VCM). Participating parties are relatively flexible in designing their cooperation and rely on national administrative frameworks to facilitate trading. The UNFCCC provides guidance to ensure that the transactions comply with rules on transparency, accounting practices and environmental integrity. Parties participating in a cooperative approach under Article 6.2 must appoint an authority responsible for the authorisation of ITMOs (Designated National Authorities). They must also use national or third-party registries or use the centralised UNFCCC’s International Registry for ITMOs, which tracks all exchanges (including from other registries) and is set to become interoperable with Article 6.4, as well. Finally, they must fulfil reporting obligations, including initial reports, annual information, and biennial transparency reports (BTRs).

Article 6.2: What are the open issues and next steps?

As of March 2025, 97 bilateral agreements between 59 countries were adopted, and 155 pilot projects were recorded under Article 6.2 (UNEP CCC, Article 6 Pipeline). These numbers indicate a growing relevance of the instrument, whose implementation had stalled for many years. Reasons for the slow uptake of trading under Article 6.2 are the lengthy development of national implementation frameworks, a persisting uncertainty on rules and registries, and a lack of trust in the mechanism’s environmental integrity. At the Conference of the Parties in 2024 (COP29), the UNFCCC concluded negotiations on these issues by adopting further guidance on cooperative approaches.

One of the main concerns linked to Article 6.2 is the risk that ITMOs may be counted towards the NDCs of both the host and the acquiring countries. To avoid double-counting, parties must apply so-called corresponding adjustments reflecting the correct transfer of a given emission reduction from one country to another. Minimum standards for authorising, registering and reporting on ITMOs are intended to avoid the risk of double-counting. Additionally, trades are subject to automated consistency checks and technical expert reviews. Nonetheless, the checks primarily assess the coherence of the accounting and do not evaluate the quality of the carbon credits themselves. Furthermore, flagged inconsistencies in accounting will likely remain without binding consequences. Altogether, parties are flexible in the authorisation, registration and reporting process, and further regulation may be needed to rule out double-counting and trade with low-quality carbon credits.

Another concern regards the administrative procedures, which pose a barrier to the engagement of countries with limited bureaucratic capacities. Countries willing to trade ITMOs need to institutionalise authorisation and reporting processes and determine the share of emission reductions that can be transferred without compromising national targets. The recent guidelines partly address the issue by offering UN assistance and alternative voluntary structures, such as an authorisation template and access to the UN-managed International Registry for tracking and issuing ITMOs.

What is the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism under Article 6.4, and how does it work?

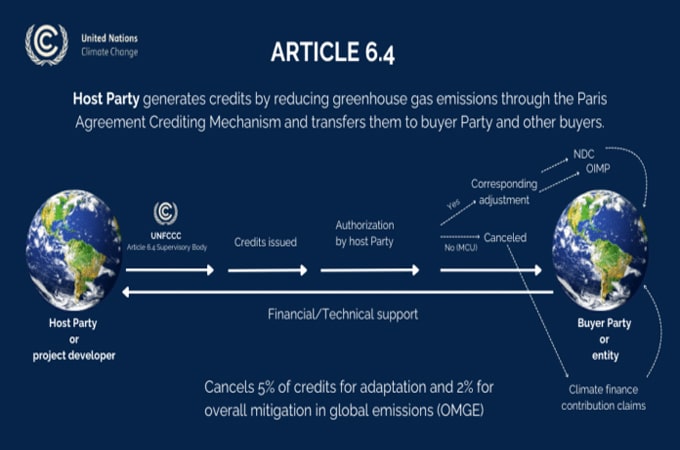

Article 6.4 establishes the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), a carbon credit market that is centralised and supervised by the United Nations. The mechanism allows countries and private actors to implement emission reduction activities that can generate tradable credits, called PACM ERs (formerly known as A.6.4 ERs). These credits can be used by countries to achieve their NDCs or by other buyers, public or private, in voluntary carbon markets. The PACM is governed by a supervisory body appointed by the UN Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA). The supervisory body is responsible for developing rules, methodological standards, and procedures to account for emission reductions or removals, approving activities, and ensuring transparency and environmental integrity. Article 6.4 builds upon and improves the Clean Development Mechanism established under the Kyoto Protocol with stricter accounting rules and broader goals aligned with the Paris Agreement’s emphasis on sustainable development and increasing ambition over time.

The mechanism also incorporates elements to promote the overall mitigation of global emissions. This is done by requiring that some credits are cancelled rather than sold, i.e., 2 per cent of PACM ERs are cancelled for overall mitigation purposes (“Overall Mitigation in Global Emissions” clause), 5 per cent of the proceeds from every transaction will be transferred to the UN Adaptation Fund (“Share of Proceeds for Adaptation”), and additional credits will be cancelled to cover administrative expenses (“Share of Proceeds for Administrative Expenses”). Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are exempted from paying the share of proceeds.

Article 6.4: What are the open issues and next steps?

The PACM is meant to offer a robust, transparent, and globally governed framework for carbon markets, built on lessons from the CDM to ensure higher environmental integrity. Compared to Article 6.2, the PACM provides a more predictable process due to its centralised body and pre-approved methodologies. This predictability may be crucial for countries, investors, and stakeholders. Nonetheless, whether the new mechanism will be successful depends on various and often technical details that will impact its overall credibility. Several open issues related to its operationalisation, integrity, and scope remain and will require further regulation and guidance.

Significant progress was made at COP29 as two standards, one on methodologies and one on emission removals, were adopted, together with other decisions on liabilities, and the establishment of a grievance mechanism. The methodologies standard outlines how emissions reduction or removal activities can demonstrate their climate benefits and compliance with the rules of the supervisory body, as well as their additionality, meaning that reductions or removals would not have occurred without the funding from carbon credits. The standard, which specifically addresses emission removals, sets out rules for monitoring and reporting, accounting, addressing reversals, and ensuring no negative environmental or social harm is caused. The supervisory body is now tasked to further elaborate the standards, to approve specific methodologies, and to set up the Article 6.4 Mechanism Registry, before the first transactions can occur (an interim mechanism registry (IMR) has been set up during this transition phase).

One major concern is the transition of projects from the CDM to the new PACM system, which is allowed during a phase that ends in December 2025. Experts have raised concerns, stating that this process could allow low-quality CDM projects to enter PACM before stricter additionality requirements come into effect. For example, an analysis by Carbon Market Watch found that the first approved transition project, a clean cookstove program in Myanmar, plans to issue 26 times more carbon credits than scientifically justified. Critics warn that similar projects could follow, issuing far more credits than their actual emissions reductions or removals warrant, potentially undermining the environmental integrity of the system.

Meanwhile, market uncertainty remains, with buyers and investors still facing unclear rules and delays in the approval of methodologies. The supervisory body is faced with balancing the need for regulatory stability by limiting frequent changes with the need for refining and developing the system to live up to its environmental and social ambitions. The issue is increasingly urgent as some key jurisdictions, including the European Union, recently indicated their willingness to invest in Article 6 credits as a form of climate diplomacy and to achieve their own climate goals.

How do these different mechanisms, approaches and markets interact?

Recent developments regarding Article 6 at the UNFCCC level have laid the basis for a properly functioning global mechanism, the PACM, and led to the establishment of key minimal instruments, such as the Registry, for more structured bilateral cooperation under Article 6.2. Despite the recent price drop, many experts expect the international trade in carbon credits to pick up in the coming years, not least because several countries have integrated or are considering ways to integrate the use of carbon credits in their domestic emissions trading systems (for instance, China, Japan, Brazil). Parallelly, the voluntary carbon market continues to operate. The carbon credit market landscape is hence becoming increasingly complex, particularly as various connections between different mechanisms are emerging.

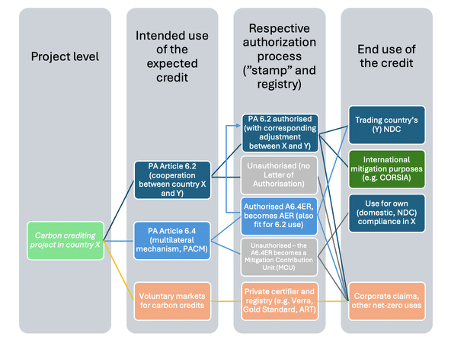

To better understand the relationship between the different mechanisms, it is useful to adopt the perspective of a project developer. From the viewpoint of project developers (e.g. a public or private entity developing an emissions reduction project expected to generate carbon credits), it is essential to understand the intended use of a carbon credit. This determines which entity must authorise it and what type of emissions reduction unit it will ultimately become. As said, methodologies in the creation of credits matter, as does the expected end-use of those credits. In theory, the same project developer can generate different credits for different end-uses, and choices will then be made based on price forecasts (thus, return on investment), access to the possibility of having the credits recognised as ITMOs (often through lengthy formalities and based on the country’s administrative capacity), and on specific demands from prospective buyers.

How is a carbon credit created?

Carbon credits are generated by projects that claim to reduce or remove GHG emissions compared to what would have happened in the absence of the project. To measure the emissions reduced or removed, a so-called baseline scenario is created to estimate the amount of GHG emissions that would have been emitted if the project had not been implemented. This hypothetical scenario becomes the benchmark against which actual emissions are measured after the project is implemented. The difference between the baseline emissions and actual emissions is considered the amount of GHG avoided or removed. This calculated reduction forms the basis for issuing carbon credits, typically one credit per metric ton of CO₂ equivalent.

However, because the baseline is hypothetical, its accuracy can be difficult to prove, leading to debate about the number of credits that should be issued. To increase credibility, third-party auditors are meant to validate the project’s methods and data and verify that the claimed reductions are legitimate. Still, concerns remain around the consistency, transparency, and long-term integrity of some projects and the standards under which they operate. Once verified, credits are issued by a recognised carbon standard body and can be sold on voluntary or compliance markets.

What are high-quality carbon credits?

In recent years, voluntary markets for carbon credits have experienced increased public scrutiny over the quality of credits, also as a result of press scandals related to projects which found massive over-crediting with respect to their actual mitigation contributions. This led to a global decrease in voluntary transactions, low prices, and diffused mistrust in carbon credit markets overall. In fact, a recent meta-study estimates that less than 16% of the carbon credits issued to 2,346 investigated projects constituted real emission reductions.[1] The problem lies in measuring carbon reductions and verifying the added value of carbon removal projects.

As mentioned above, since baseline scenarios make assumptions about the future, they are inherently uncertain. On top of this, it can be technically challenging to measure actual emission reductions or removals accurately, in particular in the case of nature-based solutions, like afforestation. Nature-based solutions also carry the risk of releasing carbon that was once captured and stored, for example, if a forest that was protected later burns down or is cut down (non-permanence). In addition, critics point out that it is difficult to prove that emission reductions would not have happened anyway, even without the funding from selling carbon credits (lack of additionality). There also might be a problem of carbon leakage, where reducing emissions in one place causes them to increase elsewhere. Lastly, carbon credit projects can negatively affect local communities if land use and community involvement are not carefully considered.

In other words, a carbon credit is only of high quality when it is additional (meaning that the emission reduction or removal would not have happened in absence of the crediting project), when it leads to a reduction or removal which respects minimum permanence requirements (with very different definitions of permanence depending on the type of project and use) and when the use of that credit implies measurable co-benefits for the human and natural environment in the project area, also with due respect to human rights and the rights of local communities and Indigenous Peoples.

How do legislators guarantee that carbon credits lead to real, additional and permanent emission reductions?

In the absence of multilateral guidance until COP29 in 2024, some multistakeholder initiatives attempted to fill the gap by proposing frameworks on credit integrity, e.g. the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM). High-level declarations on credit quality and integrity have been published by the G7 in 2023 and by national governments, such as the USA governments, such as the USA, and Brazil. Similarly, declarations and principles on quality and integrity in the use of credits have been published at the UN level, and initiatives setting standards for businesses included provisions on the quality of the use of credits in net-zero corporate strategies (e.g. SBTi, GRI). Some countries or regulators are also contemplating the idea of including international credits in their instruments to reach their climate targets. Recently, the European Commission indicated that the EU climate target for 2040 will include flexibilities based on the use of “high-quality international carbon credits” from 2036 onwards.

Moreover, recent policy developments in the UK and the EU are leading to different interpretations and approaches. The UK Government, for example, recently stated that a removal credit can be eligible for ETS integration only if it respects a minimum permanence requirement of 200 years; under the California cap-and-trade system, on the other hand, minimum permanence is 100 years. This clearly has an impact on the type of credits exchanged and allowed, as it is unlikely that nature-based solutions based on forests can respect a 200-year permanence requirement. Phased approaches involving different types of credits will therefore play a key role in the building-up of upcoming climate policy frameworks featuring some use of removal carbon credits.

Conclusion

Altogether, Article 6 has come a long way since the adoption of the Paris Agreement and has the potential to develop into a crucial global climate policy instrument, also as part of the national policy toolbox of some key jurisdictions, including the EU. Yet, the road to full implementation is rocky, and its success will depend on the diligent efforts of all stakeholders to address concerns about the environmental and social impacts of the system. Moreover, stricter methodological standards under the PACM compared to Article 6.2 are creating two de facto separate regimes with different integrity standards, between which countries seeking collaborative climate action will have to navigate in building their own market-based cooperation framework.

The debate around credit quality and integrity is deeply linked to developments under Article 6 as key jurisdictions, including the EU, signalled that future policies relying on carbon credits should be grounded in Article 6 mechanisms. This raises several important questions: Will the focus be on Article 6.2 or Article 6.4? Will jurisdictions rely on both, or potentially on other voluntary frameworks and principles? Will emerging credit rating agencies play a role in the integration of credits into compliance markets, and who will define whether a credit is of high quality or not, beyond Article 6 authorisation?

Do you want to know more?

If you want to know more about this topic, you may contact the FSR climate experts. Please, write your message to chiara.canestrini@eui.eu.

This Cover-the-Basics benefited from the contribution of Lea Heinrich and Jacopo Bencini.

[1] Probst, B. S., Toetzke, M., Kontoleon, A., Bertram, C., Grunewald, N., van den Berg, N. J., Lanzi, E., Lin, H.-C., Mardani, S., Willner, S. N., & Edenhofer, O. (2024). Systematic assessment of the achieved emission reductions of carbon crediting projects. Nature Communications, 15, 9562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53645-z