Addressing gender equality in the energy sector

Highlights from the debate: Gender equality and diversity in the energy transition

This #FSRDebate aimed at reviewing the current situation with gender participation in the energy sector and at identifying which policies and measures should be pursued to ensure equal opportunities in this sector. It also considered the extent to which affirmative actions could be used to address the current gender imbalance, and how these actions could be compatible with a merit-based approach to entry into the sector.

In fact, the energy transition, with the penetration of new processes and technologies, will provide a unique opportunity also to address the current gender imbalance in the energy sector. Moreover, while gender is increasingly a multi-dimensional notion, the main focus in the energy sector is currently on the male-female composition of the workforce.

Because of the multi-disciplinary dimension, renewable energies and other developments associated with the energy transition (e.g. decentralised energy systems) seem to exert a greater appeal on women and provide greater opportunities to them, than the more traditional fossil fuel industry[1]. Still, in renewables, women’s participation is much lower in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) jobs than in administration.

The Debate was hosted by Alberto Pototschnig (FSR), who also moderated the discussion together with Ilaria Conti (FSR).

Insights from the panel

In her opening remarks, Paula Abreu Marques (DG ENER, EC) referred to the intention of the European Commission of leading by example and therefore to its commitment to achieve gender balance at all levels of management by 2025. And within the Directorate-General for Energy, an Equality Network has been set up to review and improve the way in which the staff works together and to ensure equal access and opportunity in the organisation.

Mr Abreu Marques then acknowledged that the energy sector has been for long male-dominated and, while there has been progress in recent years, more efforts are needed. Gender equality could be helped by the clean energy transition, which will create new jobs so as to exploit the full potential of a more diverse workforce, where no one should be left behind. She also stressed the importance of a more inclusive energy policy to shape a more equal and balanced society, also to promote female careers in energy. This is emphasised in the EU Green Deal. Even in renewables, women are still underrepresented in STEM jobs. She then mentioned the action that the Commission is taking to promote greater equality in the energy sector. They include addressing gender equality across the policies, raise the profile of women, and make the sector more attractive to women. Moreover, for the first time, the Commission has an Equality Commissioner, Helena Dalli, who has issued a Strategy for Woman Rights and the Commission is committed to assess the impact on women for all policy initiatives. Better data is also essential for taking effective action.

Finally, Ms Abreu Marques announced the forthcoming EU Equality Platform for a change in the energy sector, to foster equality in the sector and create workplaces that are more inclusive. The Platform will be launched by Commissioner Simson on 25 October.

After the opening statement of Ms Abreu Marques, Ms Celia García-Baños (IRENA) presented some of the results of a recent Report on Renewable Energy: a Gender Perspective.

Over the next thirty years, the number of jobs in the renewable energy sector in IRENA member countries will increase almost fourfold, from 11 to 43 million. In renewable energies, the share of women in the workforce – 32% - is higher than in other parts of the energy sector, but this share is only 28% is STEM jobs. In the wind energy segment, the share of women is much lower – 21% - comparable to other parts of the energy sector. The main identified barriers for the low participation of women in the energy sector appear to be the perception of gender roles, cultural and social norms, and prevailing hiring practices.

When it comes to the professional advances of women, the “glass ceiling” seems to be related to, again, cultural and social norms, lack of flexibility in the workplace, and lack of mentorship opportunities. Ms Celia García-Baños concluded by referring to the Identified policies and measures to redress the gender inequality: mainstreaming gender perspectives, creating networks and supporting mentorship, providing access to education and training, gender targets and quotas, workplace policy and regulations, and work-life balance.

Silvia Manessi (Head of HR at ACER, the EU Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators) and Jennie Stephens (Director of the School of Public Policy and Urban Affair, Northeastern University) animated the ensuing panel debate.

Dr Manessi started by remarking that gender is a social concept, not only related to sex, which is becoming more fluid with the new generations. She also stressed that in any debate on gender mainstreaming, everyone participates with their different background and different maturity. However, the final aim of the current effort towards gender equality and diversity is not always clear. One motivation is clearly justice and equity. But there is also a business case, in the sense that a diverse workforce is also a better workforce. The final aim would be a society and workplaces where gender no longer matters. In order to get there, Dr Manessi indicated that the starting point is taking stock of the current situation by having meaningful statistics. Then, there is a main barrier to overcome – unconscious biases – and time and effort need to be devoted to manage the required changes in many aspects of any organisation, following a clear fil rouge. For example, in job descriptions, the ability to foster a diverse working environment should always be included, even for the most technical jobs. Dr Manessi then referred to some good practices from the EU agencies, for example in Frontex (which champions in their communication the role of women in border patrols), or FRA (with “WE” statements on gender equality and diversity). More generally, internal objectives for managers related to gender diversity could be introduced by any organisation. These do not necessarily impose a gender-balance, but an awareness of the importance of gender equality and diversity in the workplace.

Dr Stephens started by stressing the need for a profound transformation of the energy sector, due mainly, but not only, to climate change. This transformation is so radical that we will be unable to be successful unless and until we have a more diverse and inclusive energy sector. It is becoming very clear that when women and people of colour and from other marginalised groups are given an opportunity to provide a greater contribution to the energy sector, they bring into the picture different perspectives, but also a different perception of risk, which may change the practices and priorities in the business and promote innovation. Dr Stephens then referred to her recent book “Diversifying power: why we need antiracist, feminist leadership on climate and energy” in which she highlighted that so far the climate and energy policies have not been created with diverse input and this is part of the reason why the energy transition has been lagging behind and the wealth and income gaps are increasing. In her own experience, Dr Stephen found white male-dominated technocratic approaches to energy tend to be narrower than if they were developed in a more diverse setting.

Views from the audience

After a first round of contributions from panelists, four polls were used to collect views from the general audience.

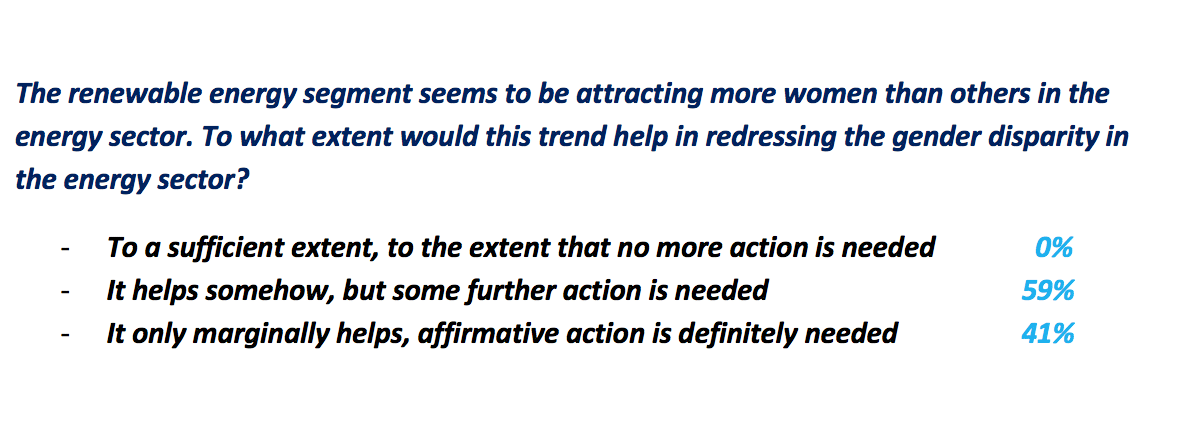

The first question referred to the renewable energy segment attracting more women than other segments in the energy sector and asked participants to what extent this trend could help in redressing the gender disparity in the energy sector.

The majority of respondents acknowledged that the penetration of renewable energies would help somehow, but more action is definitely needed, with a large minority being more sceptical about the role of the energy transition in redressing, by itself, the gender disparity in the sector.

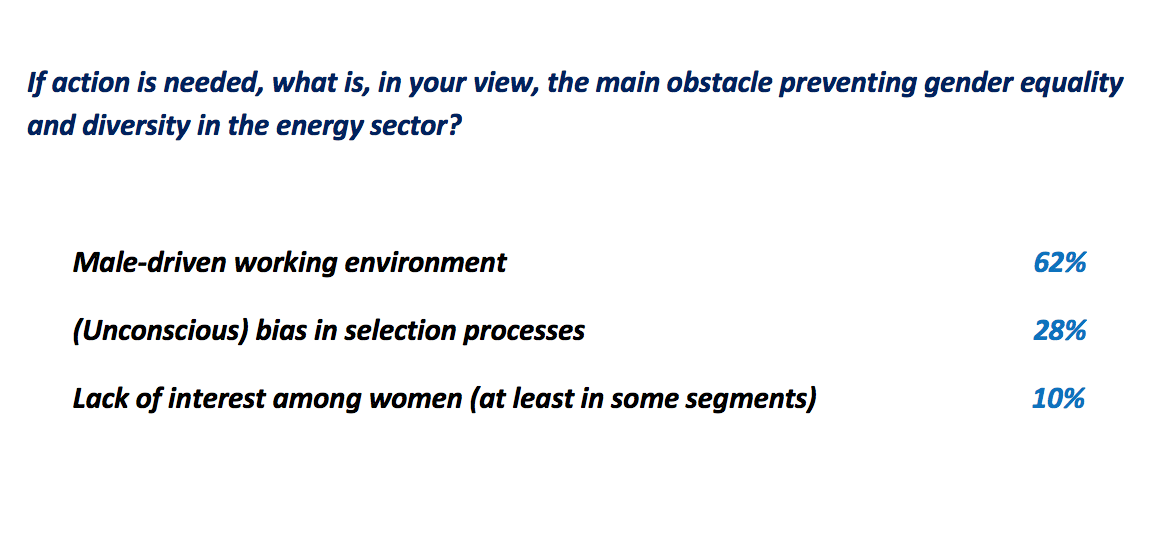

The second poll asked participants about the main obstacle preventing gender equality and diversity in the energy sector.

The majority of respondents indicated a male-driven working environment as the main obstacle to gender diversity in the energy sector.

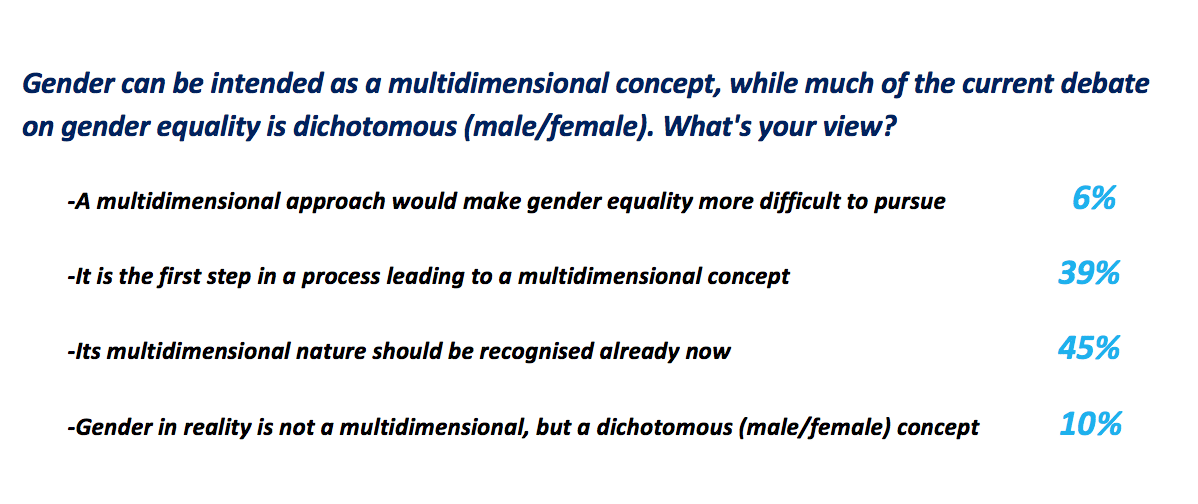

The third poll referred to the fact that, while gender can be intended as a multidimensional concept, much of the current debate on gender equality is dichotomous (male/female) and asked participants why they believe this to be the case.

Respondents were almost equally split between an urgency to consider the multidimensional nature of gender already now and the need to transition towards that approach at a later stage.

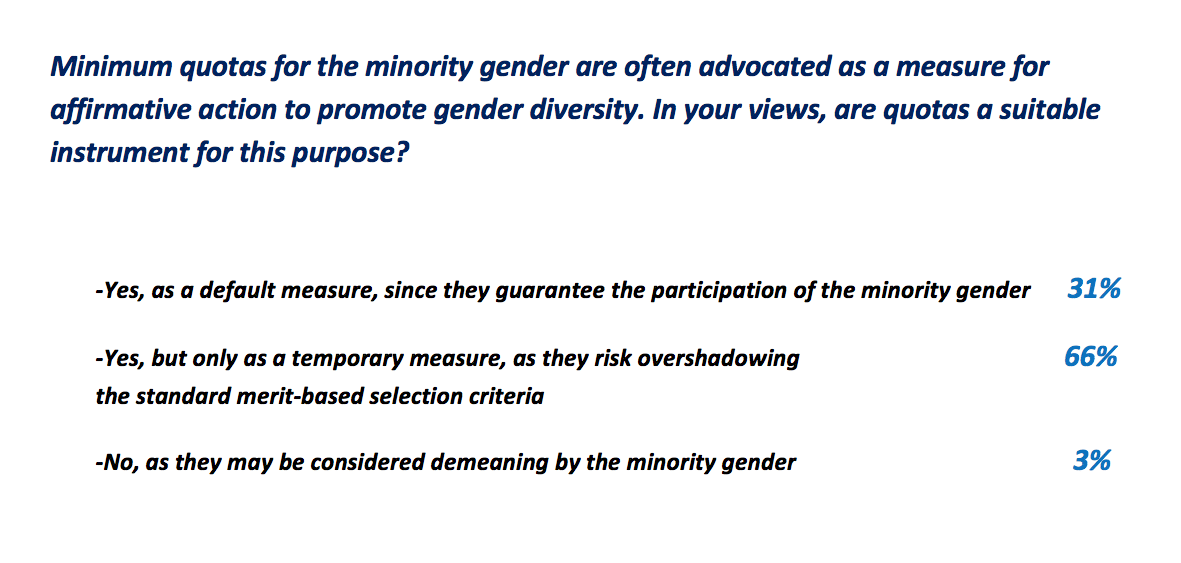

The fourth poll asked participants about the role of minimum quotas to promote the involvement of the minority gender.

A large majority of respondents acknowledged the suitability of minimum quotas, but only as a temporary measure, as they risk to overshadow the standard merit-based selection criteria for accessing the sector.

The panelists and speakers of the opening part of the debate then commented on the results of the polls and addressed a few specific questions from the audience.

Another step towards gender equality: the #Energybase

Since the launch of the Lights on Women Initiative in 2017, the FSR is supporting inclusive regulation and policy by promoting training and advocating for women in energy, and inspiring the sector to do the same.

The Energybase is an open access crowdsourced platform of female experts in energy, climate, and sustainability that will become a tool for energy stakeholders and professionals seeking to connect, engage, and exchange. Stay tuned!

[1] According to the results of a recent survey carried out by IRENA (Renewable Energy: a Gender Perspective, 2019), women represent 32% of the full-time employees in the renewable energy sector – substantially higher than the 22% average in the global oil and gas industry.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights