Written by Marie Vandendriessche

This Topic of the Month will zoom in on the EU’s Energy Union, and particularly a novel part of it: the Governance regulation proposed by the Commission in November 2016, which is currently traveling along the legislative pipeline. This final post will slip into that pipeline, offering a view of the political struggle that is taking place at the European Parliament and the Council (TTE) levels. The outcome of this political debate will ultimately determine the effectiveness of the Governance regulation.

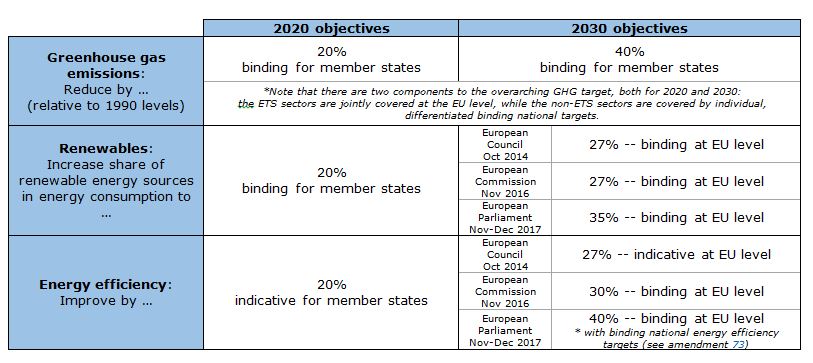

The switch from the 2020 to the 2030 energy and climate framework was the result of a political struggle, and the same would hold true for the proposed Governance regulation. When the European Council decided to move to EU-level renewables and energy efficiency targets for 2030, states such as the UK and Eastern European countries (which had argued in favour of more flexibility for member states to achieve the energy and climate goals) were left satisfied. However, member states that had argued for binding, national-level targets for 2030 and lost – such as Germany, France, Italy and the Scandinavian countries – worried that the new framework would not be effective.

As explained in the second post in this series, the major question was: how it could be ensured that the member states’ individual contributions would add up to the collective EU-level renewables and energy efficiency goals? To the member states that had argued for nationally binding targets, a robust and reliable Governance system would be critical, as the only way to ensure the Union’s goals would be met.

The year since the Commission proposed its Governance regulation has thus been filled with political debate. At the European Parliament’s ITRE (Industry, Research and Energy) and ENVI (Environment, Public Health and Food Safety) committees, the regulation was studied and debated extensively, leading to some 1700 proposed amendments at a certain stage. At the Energy Council meetings, the beginning of 2017 saw member states tentatively taking positions on the Governance issues; this evolved into full-on debates and proposals in the latter half of the year.

In December 2017, many of these discussions temporarily came to a head. At a marathon, 15-hour, Council session on December 18 (which addressed three other elements of the Clean Energy Package in addition to the Governance proposal) EU ministers ultimately reached agreement on a ‘general approach’ (i.e., negotiating position) to the regulation. At the European Parliament, a modified text passed in a joint ITRE-ENVI vote on December 7, by 61 votes for, 46 against and 9 abstentions. However, this proposed text must still face a vote in the plenary, which is currently scheduled for January 17 in Strasbourg.

During the late hours of the Energy Council in December, disagreements on the Governance of the contentious renewables target nearly derailed discussions. The Parliament had followed the Commission in opting for a linear trajectory – that is to say that both member states individually and the EU collectively would be required to increase the share of renewables in their energy consumption in a linear fashion up to 2030 (when the overarching 27% goal would be met). Many ministers in the Council, however, argued that states needed more flexibility in their trajectories in order to achieve the investment needed to reach the target.

The Estonian presidency, therefore, suggested an indicative, non-linear trajectory with two reference points, or milestones, both at the EU and member state level: 22.5% in 2023 and 40% in 2025.[1] These points were designed to help avoid a ‘hockey stick’ trajectory, where member states would take advantage of the flexibility and little to no investment would be made in renewables until just before the 2030 deadline. At the December 18 debate, France, Germany, Sweden and Luxemburg, among others (i.e., those countries that would have preferred nationally binding targets for 2030) pushed to add an additional (75%) reference point in 2027 and to increase the ambition of the 2023 and 2025 milestones. After late-night negotiations, the Council settled on 24% for 2023, 40% for 2025, and 60% for 2027. In case the reference points were not met, member states would need to implement additional measures to reach the milestones.

The Council also debated the tools available if ambition or delivery gaps were discovered, such as the recommendations that the Commission would give to member states in case it detected a gap in ambition between a state’s draft integrated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) and the necessary trajectory towards the 2030 target. The energy ministers underlined that those recommendations would be (a) non-binding (this was already the case in the Commission’s proposal) and (b) non-quantitative (this is a change with respect to the original proposal, and one the Commission argued against repeatedly). In other words, although the Commission would be able to use quantitative data in its analysis of the member states’ mid-term plans, its recommendations would have to remain qualitative in nature. This step would arguably decrease further the potential effectiveness of this non-binding tool.

Both the Council and the Parliament furthermore added detail on the financing platform for EU-level renewables projects (which the Commission proposed as a gap-filling mechanism in case the collective Union-level renewables goal appeared unlikely to be met), stipulating that member state contributions would be voluntary. The Council, moreover, included some more precise provisions on the shape of the support offered by the financing mechanism and defined more strictly how it would be applied in member states.

In terms of the timelines for the planning and reporting phases, both the Parliament and the Council introduced some changes. Some were pragmatic, such as delaying the deadline for member states to submit their draft NECPs,[2] and requiring the Commission to submit its recommendations on draft NECPs within a tighter timeline (so that member states would have time to make the necessary changes). Others were connected to long-term planning for energy and climate policies: interestingly, both the Council and the Parliament added more emphasis than the Commission had on the Paris Agreement and gave the long-term strategies a larger role (see Duwe, 2017 for a detailed view of this alignment). The Parliament, in particular, attempted to realign the timeline of the Governance processes with those under the Paris Agreement (note that the EU aims to play a leading role in the Paris process, which was designed around the same time as the EU’s 2030 energy and climate framework. This will require strong energy and climate Governance on the part of the EU, including clear alignment with the Paris cycles).

Meanwhile, and as was to be expected given the Governance regulation’s cross-cutting role across energy and climate policies, some member states attempted to link issues in Governance with other components of the Clean Energy Package. Potential modifications of the 2030 targets decided by the European Council in 2014, for instance, were followed with great interest (see below for a table of the Commission and Parliament’s current proposals; the Council of Ministers maintained the original targets determined in 2014 by the European Council).

Yet other issue linkages were also used in the negotiations. Spain, along with Portugal and France, for example, succeeded in placing more emphasis on electricity interconnections – one of the most important energy topics for them, especially Spain, which has high potential to export its renewables generation – in the Governance package. The Council’s ‘general approach’ text now calls for member states to include a strategy to achieve at least 15% in electricity interconnection by 2030 in their NECPs (though each new interconnector would be subject to socio-economic and environmental cost-benefit analysis) and includes a provision where the Commission would ‘cooperate’ with member states in 2026 in case the 2025 assessment reveals that progress towards the interconnection target is insufficient.

In addition, in Parliament, further issues were added into Governance or were given a more prominent role. The Parliament’s current text, for instance, (a) includes energy poverty in the planning and reporting obligations, (b) establishes a new, multi-level energy dialogue platform, (c) stresses that all parts of the Governance process be transparent to the public (including Commission recommendations and member state justifications in case they deviate from the recommendations), (d) establishes a Just Transition Initiative for workers and communities affected by the transition to a low carbon economy and (e) calls for a new concept of cross-border Renewables Projects of EU Interest (RPEIs).

Although the debate has been intense up to now, it is far from over. The Parliament is yet to confirm its position, after which trilogue discussions (Parliament-Council-Commission) must begin to reach a final compromise text. These negotiations will not be a walk in the park: the Parliament has taken more ambitious views than the Council, opting for a linear trajectory for the renewables goal and higher renewables and efficiency targets overall. In addition, it has asked for more transparency in the Governance process, while the Council has built in more flexibility for member states to achieve the targets.

The outcome of these discussions will ultimately define the effectiveness of the Governance regulation, answering the question: Will the EU will be equipped to bridge any gaps that might arise in the national-level implementation of EU-level 2030 energy and climate goals?

[1] For these reference points, 0% would represent the share of renewables as established in the 2020 targets (20%), and 100% would be the 27% target of 2030.

[2] Whereas the Commission had called on member states to submit their draft NECPs for the 2021-2030 period by January 1, 2018, the latest State of the Energy Union revealed that only seven of the EU’s member states are in an advanced phase in the preparation of these plans: Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK. All other member states still find themselves in the initial stages of drafting. Both the Parliament and the Council’s proposals, therefore, delay the deadlines for these plans, though the Parliament maintains a more ambitious deadline.

References

Duwe, M. & Freundt, M. (2017). Happy Birthday, Paris Agreement! Here is how the EU will be celebrating. [Report]. Retrieved from the Ecologic institute website: https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/files/publication/2017/governance_regulation_-_paris_assessment_-_20171205.pdf

Vandendriessche, M., Saz-Carranza, A. & Glachant, J.-M. (2017). The Governance of the EU’s Energy Union: Bridging the Gap? [Working paper]. Retrieved from European University Institute website: http://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/48325