The Green Deal Industrial Plan

What is the Green Deal Industrial Plan? What are critical raw materials, and why do they matter? What is the EU doing about critical raw materials? Where is the EU currently standing on clean tech?

This article discusses the Green Deal Industrial Plan. We explore the objectives of this EU strategy and consider the operating mechanism of two of its principal pillars, the Critical Raw Materials Act and the Nez-Zero Industry Act.

While the European Green Deal’s objective of a transition to a net-zero economy should lead to a decrease in the EU’s fossil fuel imports, the rapid roll-out of many clean energy technologies required to reach carbon neutrality by 2050 will lead to significant increases in demand for other resources and technologies, not all of which can be produced within the European Union. Against this background, the European Commission has developed the so-called Green Deal Industrial Plan, which aims to maintain or even enhance the EU’s competitiveness and security of supply as it pursues the European Green Deal. Two principal legislative pillars of this strategy have made their way through the legislative process and are now nearing entry into force. The Council of the EU and the European Parliament reached political agreement on the Net-Zero Industry Act in February 2024. The Critical Raw Materials Act, meanwhile, was formally adopted on 18 March 2024. In this cover the basics article, we ask: what is the Green Deal Industrial Plan? What are critical raw materials and why do they matter? Where is the EU currently standing on critical raw materials? What is the EU doing about critical raw materials? Where is the EU currently standing on clean tech? How is the EU attempting to boost its domestic clean tech sector? Can the EU compete with other global players?

What is the Green Deal Industrial Plan?

In February 2023, the European Commission published the blueprint for the industrial transformation necessary to support the objectives of the Green Deal, entitled A Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age. To no small extent, this strategy is motivated by the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, which exacerbated the energy crisis that had started to manifest in late 2021 and made EU countries acutely aware of the dangers of overreliance on a single import country for a resource crucial to the economy, in this case primarily natural gas. For energy, this led to the adoption and implementation of the REPowerEU plan, aimed at rapidly decreasing EU reliance on Russian fossil fuel imports while shielding EU consumers from the adverse effects of the energy cris. The aim of the Green Deal Industrial Plan is to counter the EU’s import dependency for other key commodities and technologies by placing it at the forefront of markets that will emerge or change as a result of global decarbonisation efforts. Maintaining the EU’s security of supply and competitiveness in this shifting geopolitical environment is at the core of the plan, which provides that:

“The starting point for the Plan is the need to massively increase the technological development, manufacturing production and installation of net-zero products and energy supply in the next decade, and the value added of an EU-wide approach to meet this challenge together. This is made more difficult by the global competition for raw materials and skilled personnel. The Plan aims to address this dichotomy by focusing on the areas where Europe can make the biggest difference. It also seeks to avert the risk of replacing our reliance on Russian fossil fuels with other strategic dependencies that could impede our access to key technologies and inputs for the green transition, through a mix of diversification and own development and production”.

The Commission followed up this plan in March 2023 with three legislative initiatives aimed at securing these objectives:

- A proposal for the reform of the EU’s electricity market,

- A proposal for a Critical Raw Materials Act,

- A proposal for a Net-Zero Industry Act.

The FSR has conducted extensive research on the EU’s electricity market reform proposal, the principal elements of which we summarise in this blogpost. In this cover the basics article, we focus on the latter two initiatives, that is the relevance of critical raw materials and clean tech manufacturing capacity for the European Green Deal.

What are critical raw materials, and why do they matter?

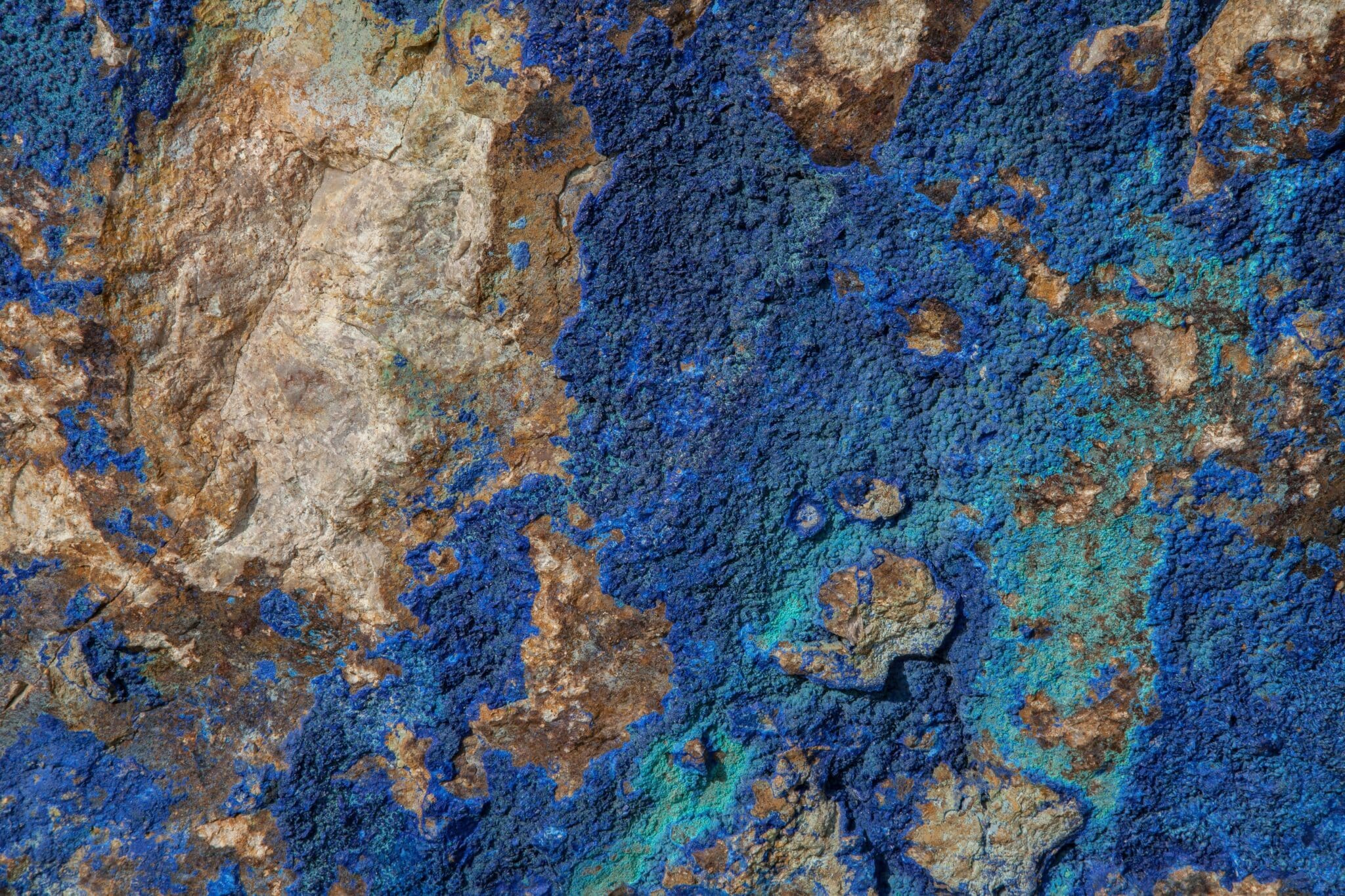

Critical raw materials (CRMs), in US discourse also sometimes referred to as ‘critical minerals’, are those resources that are seen as essential for manufacturing technologies and equipment considered to be of strategic importance. What precisely is deemed ‘critical’ thus depends on the context, such as long-term strategic objectives or market trends, domestic and global demand developments, and technology penetration assumptions. The European Union, in this context, has focused on those raw materials that are essential to support its competitiveness and autonomy as it undergoes the ‘twin transition’ of digitalisation and decarbonisation.

As we will see later, to determine whether or not to consider a raw material critical, the European Commission uses a combination of two factors: (1) economic importance and (2) supply risk. Only those materials which cross both a supply risk (SR) threshold and an economic importance (EI) threshold are considered critical, with the exception of copper and nickel, which have a low supply risk but are nonetheless considered critical due to their many applications.

The perhaps best-known example of a critical raw material needed for decarbonisation is lithium, which is needed to manufacture batteries for electric vehicles, but there are many others. Other examples include platinum, which is needed for manufacturing fuel cells and electrolysers, rare earth elements for permanent magnets needed in the generators of wind turbines, or silicon metal, which is crucial for solar PV panel technologies.

Where are critical raw materials mined and processed?

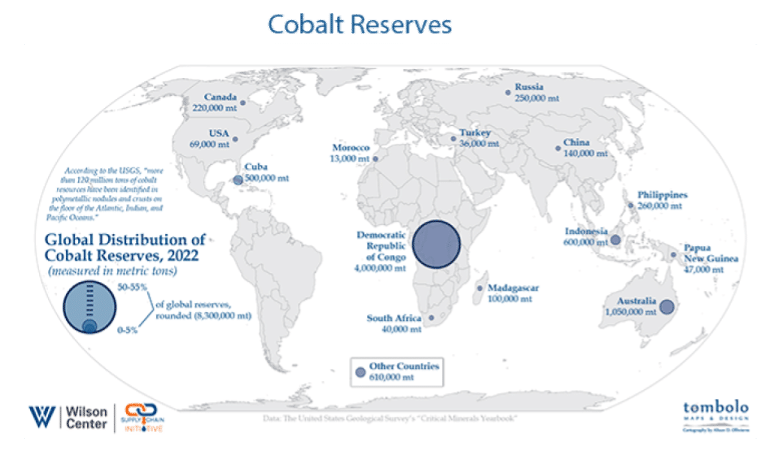

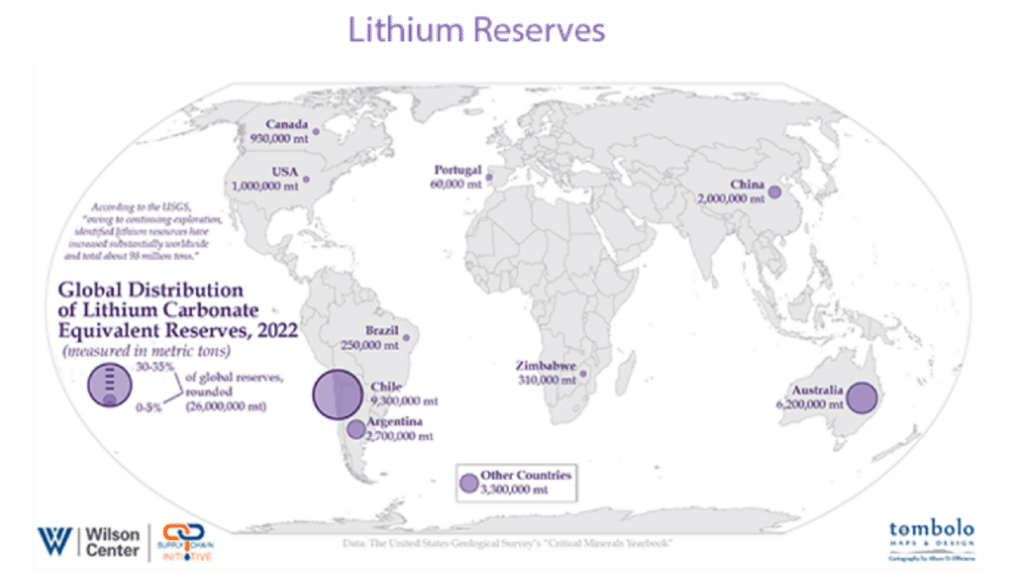

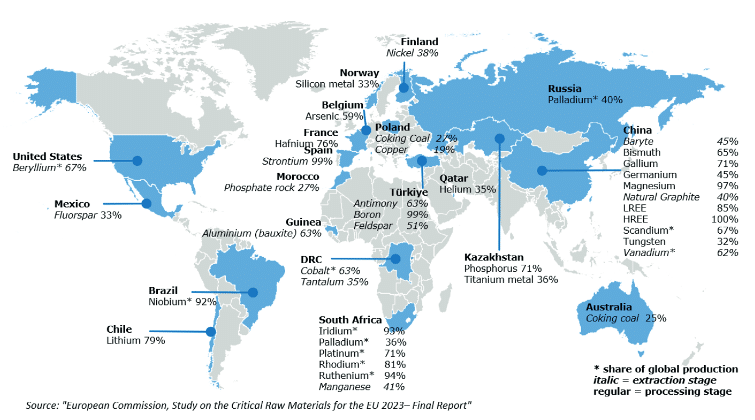

A principal factor contributing to the supply risks of CRMs is their uneven geographical distribution. Figure 1 illustrates this through the example of global cobalt and lithium reserves. Over half of global cobalt reserves are found in the Democratic Republic of Congo. For lithium, reserves are concentrated in Chile and Australia, with other countries, including Portugal, having relatively small reserves. Many other CRM reserves have a similarly uneven global distribution pattern, with sometimes even higher concentration in single countries than that shown in the maps below. South Africa, for example, is estimated to have over 90% of world platinum reserves.

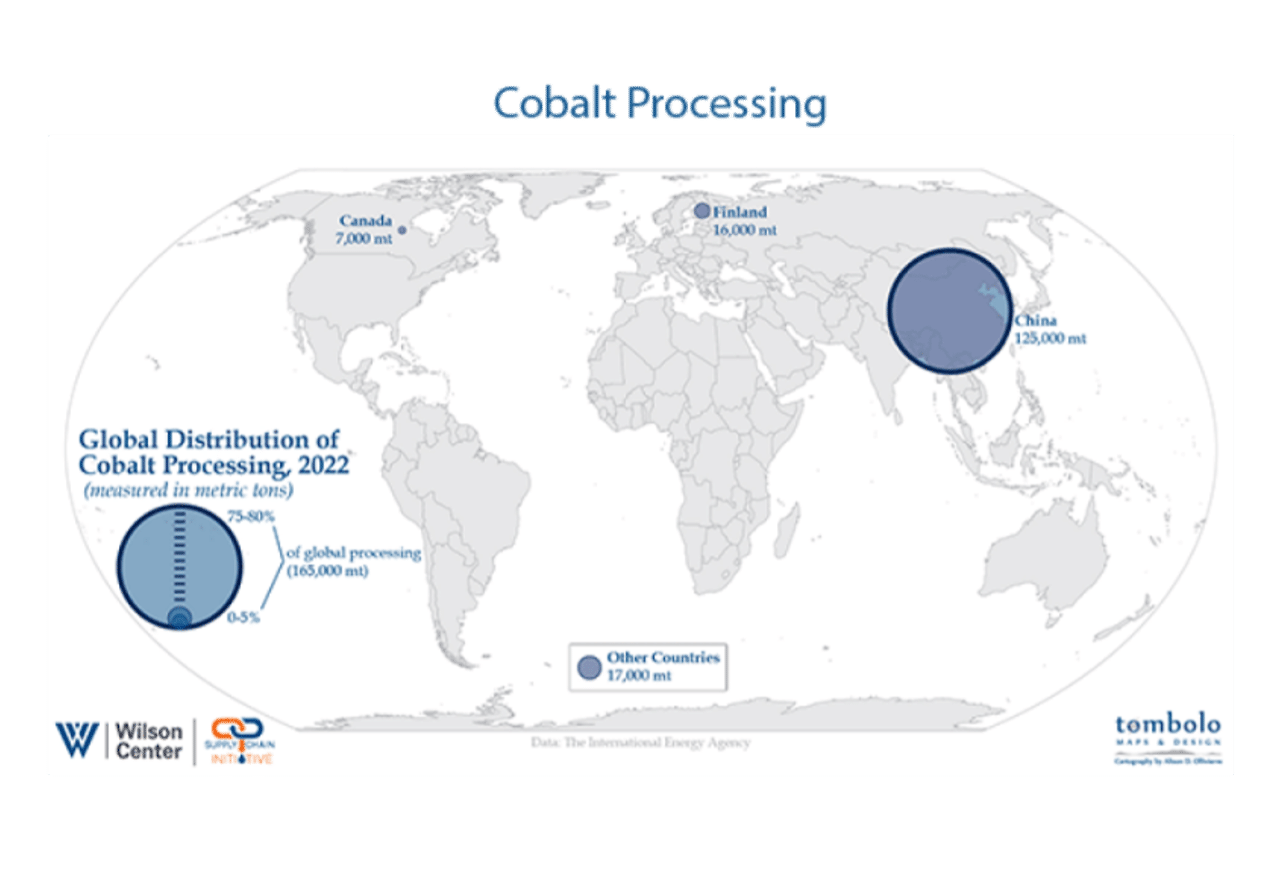

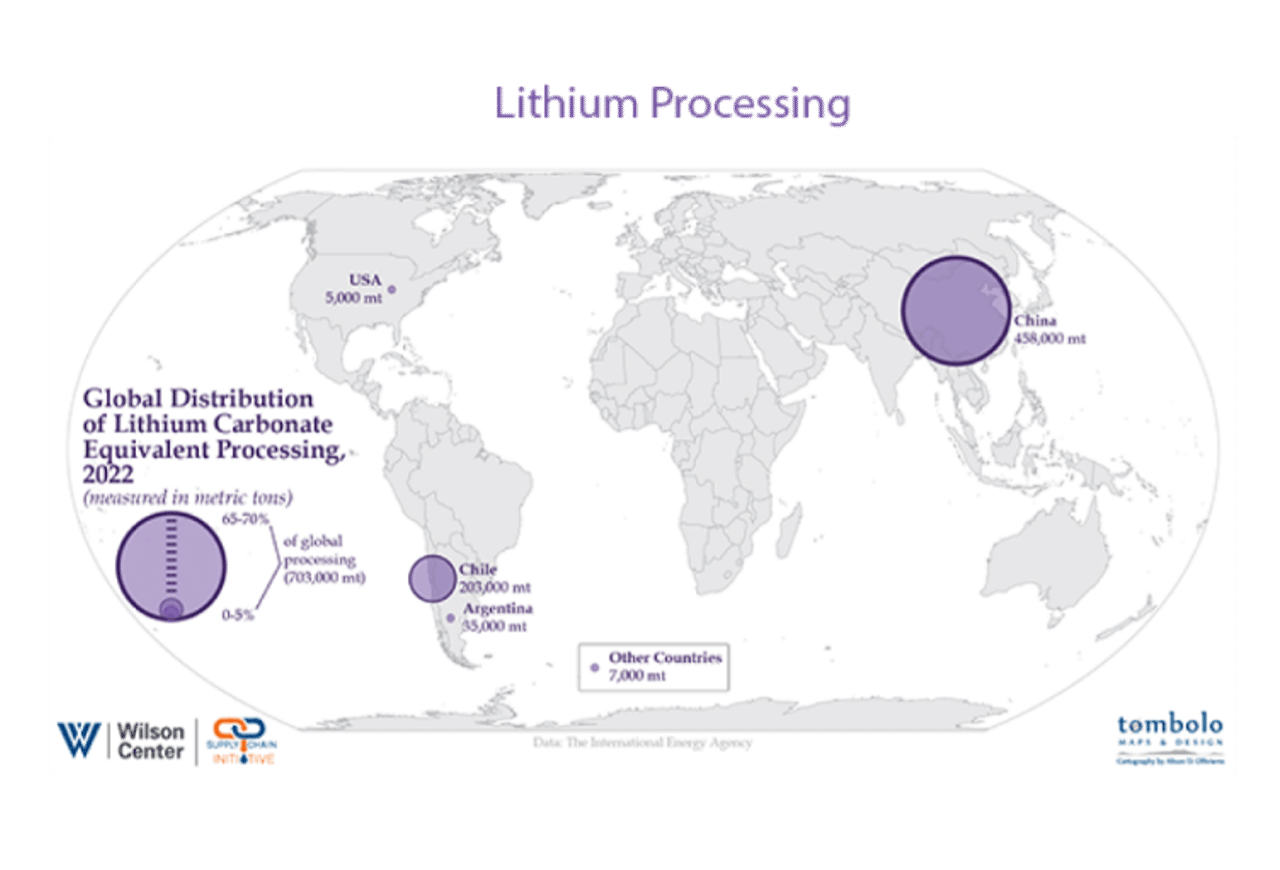

However, considerations about CRM supply security go beyond extraction and must include the entire CRM value chain, consisting of extraction, processing and recycling. Particularly in the area of CRMs processing, China has reached a dominant global position. Figure 2 below illustrates this, returning to the examples of cobalt and lithium.

Highly concentrated extraction and processing for CRMs leads to strategic dependencies due to the lack of alternatives for diversification of supplies. The negative implications of these dependencies are compounded by the expectation that demand for critical raw materials will rise exponentially over the coming decades. Research by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) suggests, for example, that a global 2050 carbon-neutrality scenario would see global lithium demand for clean tech increase from 12,300 tonnes per year in 2020 to 220,308 tonnes in 2030 and 1,090,014 tonnes in 2050. This would mean that, by 2050, the EU would require approximately 175% of current lithium supply.

Where is the EU currently standing on critical raw materials?

The EU is heavily dependent on CRM imports at every step of the value chain. Figure 3 below shows the major suppliers for each CRM. It shows that the EU is strongly reliant on imports for many CRMs; moreover, EU’s imports of many CRMs are highly concentrated, leading to strategic dependencies. For example, China currently provides 100% of EU’s Heavy Rare Earth Elements (HREEs).

The reason for this state of affairs is twofold. First, many raw materials needed for the realisation of the Green Deal objectives are simply not present in sufficient quantities in the EU. Secondly, it is often easier and cheaper, for an advanced economy like the EU, to import materials mined or processed elsewhere.

While there is some CRM mining activity in the EU, it is clear that this domestic production capacity will not suffice to cover the EU’s CRM needs. In addition, mining activities have often met with local opposition. Examples include the Barroso lithium mine in Portugal, which has faced strong resistance from residents. A recent discovery of substantial CRM deposits in Sweden on land inhabited by communities of indigenous Sámi people also raises questions of whether it is possible to reconcile the respect for indigenous rights with the extraction of these minerals .

What is the EU doing about critical raw materials?

The issue of critical raw materials is not new in the European Union. The European Commission, based on an analysis by the JRC, has published a list of critical raw materials every three years beginning in 2011, when the rapid industrialisation of economies like China, India and Brazil generated concerns about increasing scarcity of certain materials.

However, the urgency which the EU and its Member States attribute to this issue has changed. As is evident in the Commission’s Communication accompanying the 2023 list of CRMs, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing gas supply crisis has contributed to the EU taking its strategic dependencies more seriously.

This is why, in 2023, the list of critical raw materials was for the first time accompanied by legislative action, as anticipated by the Commission President in her 2022 State of the European Union Address. A Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) was thus proposed on 16 March 2023 as part of the Green Deal Industrial Plan. The European Parliament and the Council reached political agreement on the CRMA in November 2023, and the act was formally adopted on 18 March 2024.

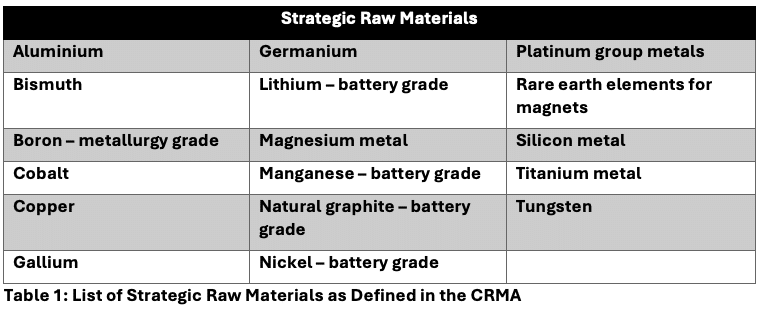

The CRMA specifies a list of 34 Critical Raw Materials, of which 17 are accorded the priority status of Strategic Raw Materials (SRMs) due to their particular importance for the EU’s twin transition (Table 1). Both lists will be reviewed by the Commission every four years.

The CRMA sets non-binding 2030 benchmarks for the EU along the entire value chain for SRMs. By 2030, the EU aims to achieve:

- 10% of extraction of EU annual demand of SRMs in the EU,

- 40% of processing of EU annual demand of SRMs in the EU,

- 25% of recycling of EU annual demand of SRMs in the EU.

The CRMA further stipulates that the EU should not depend on a single supplier country for more than 65% of its annual demand for all SRMs at any step in the value chain.

Projects associated with SRMs can be designated ‘strategic projects’. These strategic projects will benefit from expedited permitting timeframes. The act specifies that the permit-granting process should be a maximum of 27 months for extraction projects and 15 months for processing and recycling projects. The act also stipulates that these projects should have priority access to financing.

In terms of governance, the CRMA institutes a Critical Raw Materials Board to coordinate EU efforts. The act also foresees the establishment of a mechanism for demand aggregation and joint purchasing of CRMs, operating in a way similar to the AggregateEU scheme instituted under REPowerEU for natural gas.

However, even with these targets and incentives, given the EU’s heavy reliance on imports and the supply concentration for many raw materials as illustrated above, accomplishing these objectives will be challenging. In this context, it should also be noted that the act does not go hand-in-hand with dedicated EU funds, leaving the financing of raw materials projects mainly up to Member States. This contributes to a risk of fragmentation and inefficiencies in raw materials procurement, as well as the implementation of the act’s permitting and regulatory provisions at different speeds.

Where is the EU currently standing on clean tech?

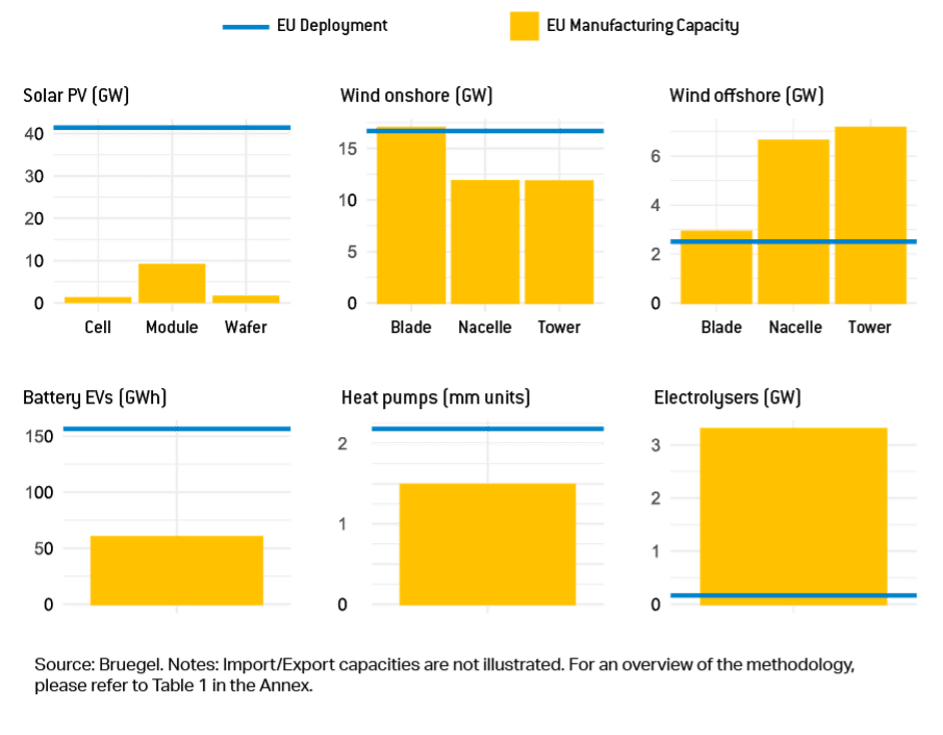

Having sufficient manufacturing capacity and skilled workforce to use CRMs to produce the technologies needed to accomplish the Green Deal’s objectives is another important part of maintaining the EU’s energy security and competitiveness in the energy transition. Unlike with the critical raw materials, where the EU is highly import-dependent for all SRMs by definition, the picture in clean tech manufacturing is more variegated. Figure 4 below illustrates this.

While for some technologies, like onshore and offshore wind, the EU currently has the manufacturing capacity to meet most or even all of its deployment needs, the situation is different in other clean tech sectors, and markedly so in the field of solar PV, where the EU is highly import-dependent.

How is the EU attempting to boost its domestic clean tech sector?

To support domestic manufacturing in the clean tech sector the European Commission in March 2023 proposed the so-called Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA) at the same time as the CRMA,. Council and Parliament reached agreement on the NZIA on 6 February 2024.

Rather than focusing on raw materials, this piece of legislation aims to retain or claw back EU competitive advantages in the clean tech manufacturing sector. This is important for security of supply, but also linked to the EU’s global competitiveness. The EU seeks to maintain a competitive edge in clean tech sectors where it is comparatively strong (e.g. wind) and reclaim its competitiveness in sectors where it has lost its edge (e.g. solar PV).

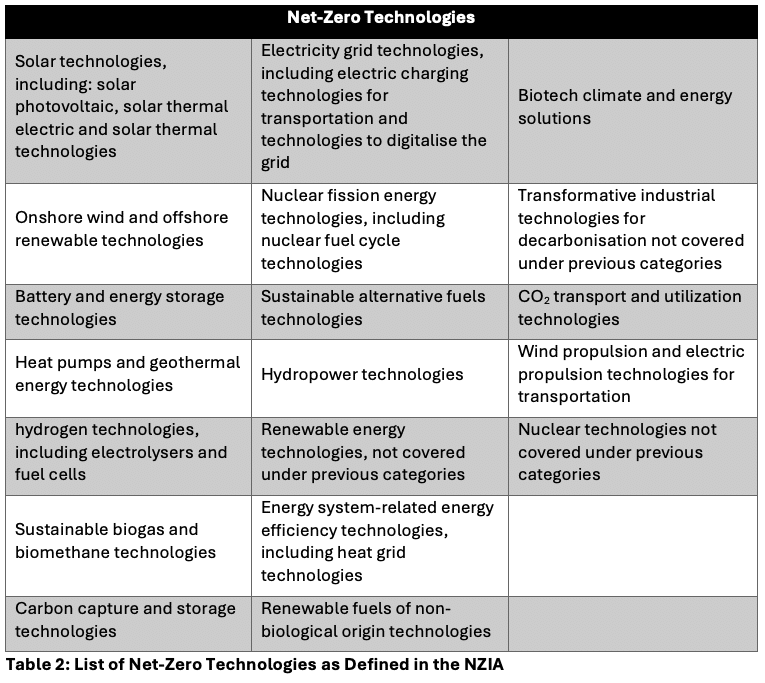

The NZIA works in a similar way to the CRMA. It identifies a list of 19 Net-Zero Technologies whose manufacturing should be supported by the EU. It is important to note that, rather than fostering innovation, the NZIA is aimed at more mature, tried-and-tested technologies. In its proposal, the Commission thus only considered technologies that had reached a technology readiness level of 8 as defined by the International Energy Agency (IEA). This means that these technologies must at least have reached the level of a first commercial demonstration at full scale. Selected technologies should also have the potential to contribute to the decarbonisation and competitiveness of EU industry, while at the same time being subject to a certain supply risk. While the Commission had initially envisaged a structure similar to the CRMA, which would have included a broader list of net-zero technologies and a smaller, privileged list of strategic net-zero technologies (analogous to the distinction between CRMs and SRMs), EU legislators in the Parliament disagreed with this approach. Additionally, in both Parliament and Council, heated political debates ensued concerning whether nuclear energy projects should be eligible for the same benefits as renewable energy technologies, such as privileged access to funding. In the end, co-legislators settled on a single list of net-zero technologies, shown in Table 2, which includes nuclear energy.

The NZIA sets a benchmark of reaching a supply capacity of 40% of the EU’s annual deployment needs for these technologies necessary to achieve the EU’s 2030 climate and energy targets. This target applies across all technologies rather than to each of them individually.

Where the EU is dependent on a single third country for more than 50% of its demand of clean tech components, the NZIA specifies that any public tenders in relation to that component must take into account the so-called ‘resilience contribution’ of the bids. The NZIA defines the contribution to resilience as ‘taking into account the proportion of the net-zero technologies or their main specific components that originates from a third country that accounts for more than 50% of the supply of that specific net-zero technology within the Union’.

Rather than some technologies being considered inherently strategic, the version of the NZIA that was adopted stipulates that manufacturing projects for any of the net-zero technologies listed in Table 2 may ask the Member State in which they are located to be recognised as net-zero strategic projects, provided they:

- Increase the manufacturing capacity of a component or a segment of the net-zero technology supply chain; or

- Provide European net-zero industries with access to the best available net-zero technology or to products produced in a first-of-a-kind manufacturing facility; or

- Manufacture net-zero technologies through practices that implement improved environmental sustainability and performance or circularity features.

Similar to Strategic Raw Materials, net-zero strategic projects benefit from expedited permitting procedures, defined in the NZIA as:

- 9 months for construction or expansion of net-zero strategic projects with a yearly manufacturing capacity of less than 1 GW;

- 12 months for the construction or expansion of projects with exceeding 1 GW manufacturing capacity;

- 18 months for the operation of a CO2 storage site.

The NZIA also establishes a governance body, the so-called Net-Zero Europe Platform, mirroring the Critical Raw Materials Board set up under the CRMA. The platform represents a forum for Member States to coordinate their efforts and discuss financing of projects as they implement the act and will also collaborate with existing clean tech industrial alliances in the EU, such as the European Battery Alliance, the European Solar Photovoltaic Industry Alliance, the European Clean Hydrogen Alliance, the Alliance for Zero-Emissions Aviation, the Industrial Alliance on Processors and Semiconductor Technologies, and the Renewable and Low-Carbon Fuels Value Chain Industrial Alliance.

While aimed at more mature technologies, the NZIA also seeks to foster innovation by encouraging Member States to establish net-zero regulatory sandboxes. The act also envisages the setting up of so-called Net-Zero Acceleration Valleys, which would concentrate projects associated with a certain technology to make them more attractive for investment. These valleys can also include dedicated innovation hubs. The EU’s Strategic Energy Technology (SET) Plan was revised over the course of 2023 to align more closely with the NZIA.

The EU is providing a financing instrument for technologies that it considers crucial through the Strategic Technologies for Europe (STEP) Platform. The STEP platform aims to efficiently channel investments from existing and new EU funding programmes towards the manufacture of strategic technologies.

Finally, the NZIA also recognises the fact that the EU needs to ensure that it has a workforce with the necessary skills to manufacture the needed technologies. To this end, the act promotes the setting up of Net-Zero Industry Academies to upskill and reskill workers, with access to EU funds for their establishment.

Can the EU compete with other global players?

These efforts at enhancing the EU’s strategic autonomy do not take place in a vacuum, but are set against the background of complex geopolitical developments. Other global players are also concerned about the rapid demand increase for critical raw materials and clean technologies and are seeking to position themselves so as to benefit from these developments.

In 2022, the US introduced the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a massive subsidy scheme heavily favouring US-manufactured energy transition technologies such as electric vehicles. As mentioned above, another global actor, China, currently dominates the supply chain for clean tech and many SRMs. Supply chain concentration and protectionist measures by major global actors illustrate that free trade alone is unlikely to lead to outcomes able to preserve EU competitiveness and strategic autonomy. In this competitive geopolitical environment, the EU is endeavouring to align itself with countries producing or importing CRMs that share its values. A so-called Critical Raw Materials Club is supposed to enable these actors to coordinate in their efforts and ensure added value for all participants.

The EU’s strategy for more secure raw materials and clean tech supply chains thus also has to respond to these other global actors’ efforts. On the one hand, the EU needs to diversify its imports by concluding partnerships with more trusted, third countries. On the other hand, future demand for clean tech and raw materials will make it difficult to break dependencies with countries that have already established significant economies of scale and will introduce an element of competition to concluding agreements with alternative import countries. Both the CRMA and the NZIA here emphasise the need for structured, strategic partnerships with third countries as a way to secure supply and thus enhance the EU’s strategic autonomy. In the case of CRMs, African and South American countries with significant mineral wealth are seen by the EU as key partners for import diversification, and there has been a strong push to conclude formal Strategic Partnership Agreements with these countries, with an emphasis on enabling the partner country to develop the entire supply chain rather than just focusing on the extraction of minerals.

If you still have questions or doubts about the topic, do not hesitate to contact one of our academic experts:

Nicolo Rossetto, Marzia Sesini, Max Munchmeyer

Relevant links

The geopolitics of the energy transition : is strategic autonomy the solution or the problem?

Critical Raw Materials, Industrial Policy, and the Energy Transition

From Resilience to Solidarity: Shaping the Energy Security of Europe

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights