The Digitalisation Problem in the Single European Sky

This is the first installment of the Topic of the Month: Exploring the Digitalisation of Transport Infrastructure: From Concept to Reality

Uncertainties of a Shift from Prescriptive Technological Regulation to a Vision-Based Policy Framework

Within the framework of the Single European Sky (SES) initiative, the European Union (EU) gained competence in the regulation of air traffic management, including the operation and development of the European infrastructure for the management of air traffic. In the broader context, international aviation law is a domain of law that has an obvious connection to technology. Its objective has always been the regulation of different aspects of moving vehicles through airspace in a secure manner. Today, aircraft are inhabiting airspaces in volumes and dimensions never seen before. One of the most important aspects of managing this aerial traffic is the provision of air navigation services and the operation of the underlying infrastructure.

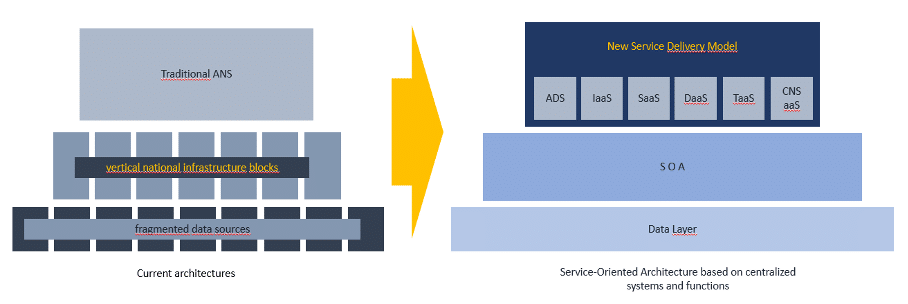

The traditional infrastructure of air navigation service provision was developed in relatively isolated national infrastructure blocks. The reason for this is that the Chicago Convention obliges states to ensure that air navigation services are provided in the airspaces under their sovereignty and also to operate the necessary infrastructure. The result is a fragmented system with limited interoperability and considerable redundancy. Since the entry into force of the Single European Sky regulations in 2004, the EU has been striving to make this system more efficient and interoperable through prescriptive rules defining obligations and deadlines for the deployment of key technologies (e.g., ADS-B, Data Link, SWIM, FF-ICE) at the EU level. The deployment of these technologies has been problematic, characterised by delays and uneven execution.

Meanwhile, the development of new digital technologies has opened the possibility of an infrastructural paradigm shift in air traffic management, in particular through the development of a network-based European air traffic data management system enabling the virtualisation and automation of the relevant activities. This potential new paradigm may be perceived as a single European air traffic data management system, a digital twin of the European airspace, where all the data relevant for the operational stakeholders and relevant authorities is accessible in real time in a uniform data format. This would enable the decoupling of services from physical infrastructure, a frictionless and efficient way to manage air traffic through location-agnostic services, large-scale real-time data analysis and intervention. The fragmented system of relatively isolated vertical national infrastructure blocks defined by national borders could be replaced by a European digital infrastructure underlying an EU data layer, and monopolistic national services providers could be superseded by a wide range of businesses providing Data as a Service (DaaS), Software as a Service (SaaS) and Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) at network level.

EU policy makers have embraced this vision with a view to enhancing efficiency, safety, sustainability and introducing the possibility of scalable service provision. Another objective is changing the traditional monopolistic business model of air traffic management by the introduction of market mechanisms enabled by technology and digital infrastructure. The vision is now described in several EU policy documents, including the ATM Master Plan, the Airspace Architecture Study, the Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda for the Digital European Sky and the Network Strategy Plan. The SES 2+ Regulation, which entered into force on the 1st of December 2024, has established or strengthened centralised functions and decision-making procedures to support the realisation of this vision.

As the title suggests, the transition to the new digital paradigm is a major challenge for the European air traffic management system. A paradigm shift needs to be achieved, but it is dependent on the willingness of a wide range of stakeholders (public and private) to:

- make the effort to understand the vision (information and knowledge aspect) fully,

- accept the vision (trust aspect),

- partially give up their sovereignty or decision-making monopoly (autonomy aspect),

- be willing to invest their limited resources into deploying new technologies and developing infrastructure in order to achieve a non-compulsory and uncertain vision (economic aspect),

- manage complexity in a dynamically evolving technological and infrastructural environment (complexity aspect),

while operating a complex and costly legacy air traffic management system as their main function (change management aspect).

Underlying these developments, there has been a change in the legal framework of the Single European Sky. The prescriptive approach (singling out technologies for deployment and defining deadlines) is being replaced by a vision-based approach.

The future vision of the Single European Sky is increasingly technology- and infrastructure-oriented. The complexity and the dimension of this infrastructural paradigm shift rule out the possibility of the traditional prescriptive approach. The emphasis is moving from prescriptive rules to soft law, policy documents, and collaborative decision-making processes.

There is also a blurring of the dividing line between hard law and soft law (for instance, while the ATM Master Plan is a technological policy document, it is arguably endowed with a certain degree of normative power through SES regulations). In this new approach, an ever-growing body of stakeholders approves the vision by endorsing it within the context of working groups, policy documents, and collaborative decision-making processes (e.g., Network Collaborative Decision-Making). A collaborative, coordination-centric environment is emerging, bypassing traditional lawmakers and public authority. Rules and decisions are not established by a sovereign entity, rather they are expected to organically emerge from a network-based collaborative process of the stakeholders involved (public and private).

At the same time, there is no legally defined roadmap of how the vision is to be achieved (the deployment plan is not fully elaborated and it is not supported by legal obligations), many of the details are missing and there is no guarantee that the potential obstacles will be overcome and the vision will in fact be realized. Furthermore, several aspects of the vision remain blurred; most importantly, the policy objectives, change management and the potential consequences of realising the vision, especially with respect to the functions, roles and autonomy that current stakeholders may retain in the changed paradigm.

This situation creates legal, economic and systemic uncertainties. Notions of autonomy, sovereignty and power are in dynamic change. The transformation of the infrastructure is also changing the perception of the law, basing the transformation process on collaborative planning and decision-making mechanisms. As the EU does not have either a clear legal mandate or the financial means to establish its own air navigation service provider, to develop its own network infrastructure and to declare the airspace over the territory of the EU its own sovereign domain, the planning and decision-making processes are expected to move the transformation process in this direction through the introduction of concepts such as a progressively more integrated airspace, the priority of the interests of the network and a technological vision of the Single European Sky.

Perhaps the most important obstacles before the realization of the vision are the sheer volume and complexity of the change, the lack of a generally accepted holistic approach, the reluctance of the Member States to give up autonomy and sovereign functions, the lack of clear legal obligations and the economic uncertainties involved that erodes stakeholders’ confidence to make the necessary investments. The perception of the vision and the level of stakeholders’ trust in its feasibility is as fragmented as the legacy infrastructure of air traffic management. Fragmented perceptions, uncertainties and a lack of trust lead to fragmented deployment. Ironically, the move to an integrated system from a fragmented system is itself as fragmented as the system that is to be transformed.

The question is how this situation may be improved. I suggest that focus areas should be identified at the policy level, and approaches should be developed and dealt with in a multidisciplinary approach to address the underlying problems:

A. Information and knowledge: addressing the lack of clarity:

- Ensure full clarity of policy objectives and consequences of policy implementation (especially with respect to the change of roles, responsibilities and reallocation of functions);

- Ensure a consistent level of information concerning the transformation between all stakeholders involved.

B. Trust: addressing the lack of conviction on the side of the stakeholders who need to implement actions to reach the vision:

- Ensure that the vision is commonly accepted; reach political agreement first, and formalize that by legislative means or in the collaborative decision-making processes only once political agreement is reached;

- When point A is accomplished, convince stakeholders about the feasibility (inevitability) and the benefits of the realization of the vision;

- Refrain from defining unrealistic target dates or objectives and obligations that cannot be fulfilled.

C. Autonomy: addressing the reluctance of states to give up autonomy or functions:

- Ensure the intensive participation of states in the development of the vision;

- Ensure a clear and concise legal basis for the vision; clarify the scope of the EU’s relevant competence and mandate – this should be reflected in the institutional framework and the decision-making processes;

- Define centralized and network-level functions unambiguously;

- Clarify the level of autonomy and which functions will be retained by the current stakeholders in the new paradigm, including Member States;

- Ensure a clear and meaningful role for the states in the decision-making process;

- Make a clear distinction between physical and digital infrastructure and consider joint Member State ownership of key elements of the physical infrastructure.

D. Economic aspect: addressing the reluctance of operational stakeholders to make the necessary investments and the resulting fragmented technology deployment landscape:

- Clarify investment needs, define feasible timelines for technology deployment;

- Design an appropriate incentive scheme and links to economic regulation (e.g. through modulation of charges);

- Ensure the availability of patient capital for common infrastructure development (e.g. consider the establishment of a fund for common infrastructure/platform development from route charges).

E. Complexity (technological, infrastructural, legal, systemic): addressing the lack of a holistic approach to understanding and deploying the vision

- Ensure a multidisciplinary approach;

- Ensure that airspace structures, centralized infrastructure (including the data layer and the central digital platform), institutional frameworks, decision-making processes and centralized functions are developed in a synchronized manner;

- Clarify technology and infrastructure needs;

- Base the transformation on existing, available technologies.

F. Change management: addressing the lack of a clear vision on how a transformation of this magnitude may be managed

- Clarify the allocation of functions, infrastructure elements and responsibilities;

- Introduce realistic timelines;

- Introduce clear legal obligations;

- Consider the creation of a pioneer network of early implementors (an expanding airspace with enhanced capabilities) following the pattern of the development of the internet.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights