Stronger incentives in grid development to go beyond business as usual

This is the third installment of the Topic of the Month on the European Grids Package

Business as usual is hardly a solution in unusual times. In the case of electricity networks, business as usual means that an increase in the demand for grid capacity is satisfied by building new lines or deploying larger transformers. However, electricity networks are not experiencing usual times: over the coming years, the European electricity system is expected to support the integration of a significant amount of additional renewable energy sources and the electrification of a large share of final energy uses. In this context, following traditional approaches to network development and operation is likely to be a recipe for delay and cost escalation. Fortunately, developments in technology, in particular in digital and power electronic solutions that allow better monitoring and control of electric cables and substations,[1] offer the opportunity to satisfy the increasing needs of electricity grid users with less investment in (new) physical assets and reduced lead times.[2]

Technology won’t be enough

However, technological innovation is not enough if we want to go beyond business as usual. Transmission and distribution system operators, like any economic actor, choose the best technology depending on the incentives they face.[3] In their case, incentives are mostly determined by the regulatory framework they are subject to as part of their franchise. In the European Union, the details of such a framework are defined at the Member State level by national regulatory authorities (for an exhaustive overview, look at the annual report by CEER). While any generalisation should be taken with caution, it is normally possible to say that most of the allowed revenues of electricity system operators are driven by the recovery of the expenses associated with investments in physical assets, including the remuneration of invested capital. If you combine this fact with the typical system operators’ duty of ensuring the continuous and secure supply of electricity, something that can be more comfortably achieved with ‘oversized’ networks, it is apparent that going beyond business as usual in electricity network development and operation might be difficult.

The European Commission is aware of the challenges associated with networks in the context of the energy transition and plans to adopt a ‘European Grids Package’ over the coming months to ensure affordable energy to European citizens and firms.

The European Grids Package should include a set of legislative and non-legislative measures that aim, among other things, at accelerating the expansion, modernisation and digitalisation of energy grids.

A proposal from the FSR

Various solutions have been proposed in order to induce regulated system operators to deploy the most efficient and effective solutions to deliver grid capacity to the producers and consumers of electricity. A symmetric treatment of operating and capital expenses has often been cited as a first step to address the so-called CAPEX bias and induce system operators to consider more extensively non-wire solutions, such as flexibility procurement, to deal with network congestion. Others have suggested going one step further and remunerating system operators on the basis of total costs (TOTEX), setting ex ante a fixed share of those costs that is entitled to a rate of return (FOCS). Finally, the provision of economic rewards linked to the achievements of certain service outputs, such as the hosting capacity in a network, rather than the productive inputs utilised, have been proposed (output-based regulation). Regulators are currently exploring these solutions, and a few countries have now adopted at least some of them (for an overview of some recent experiences and reflections by the regulatory community on the matter, look at this recent CEER report).

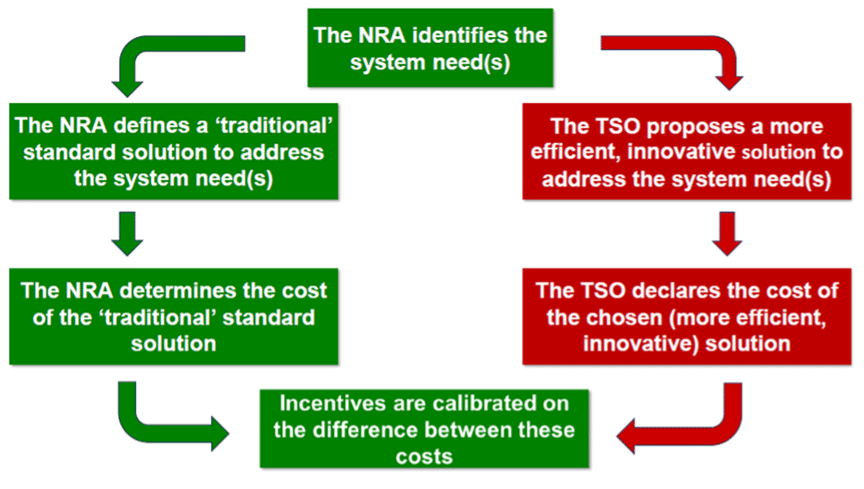

At the FSR, we have examined this issue in the context of a study sponsored by ACER and came up with a proposal for an additional scheme that regulators can include in their toolkit to incentivise system operators to explore and deploy new solutions to address system needs (see Figure 1).[4] In particular, the scheme proposed could be a useful top-up to the existing revenue-setting framework at the national level, avoiding not only the CAPEX bias of system operators when choosing the solutions to address system needs, but also promoting the adoption of more efficient, innovative solutions that are TOTEX-light and can be deployed timely.

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed incentive scheme (source: Pototschnig and Rossetto, 2024)

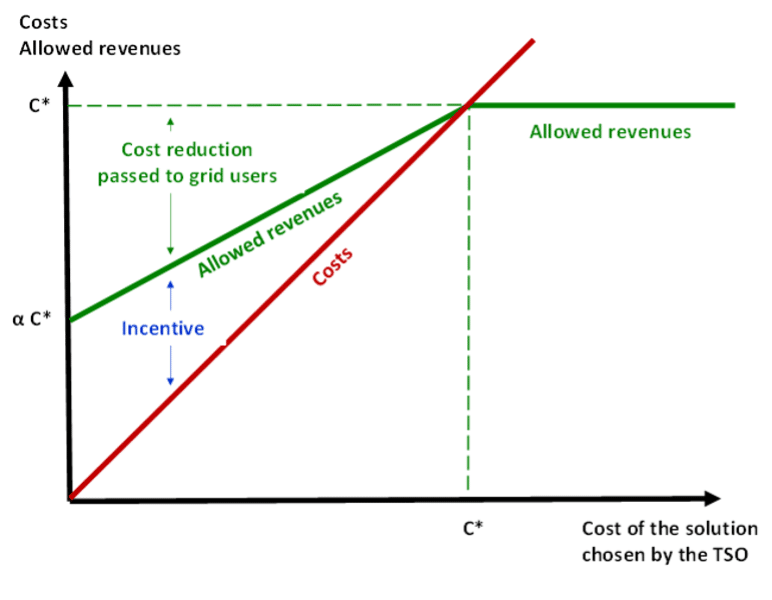

At the core of the scheme, there is the idea to share the benefits generated to the system by the adoption of the innovative solution, understood in terms of cost reduction. In practice, the scheme would reward the system operator not only with the recovery of the cost of the solution implemented, but also with a share of the difference, if positive, between the cost, stated ex ante, of the traditional solution to address the system need under consideration (C*) and the cost, also stated ex ante, of the innovative solution to address the same system need (C). The remaining share of the difference would accrue to grid users (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Allowed revenues in the proposed scheme (source: FSR, 2023)

A tougher game is worth the candle

The application of the proposed scheme to realistic case studies suggests that the value of the incentive could be so significant to motivate the top management of a system operator to duly consider the adoption of the innovative solutions instead of the traditional ones. At the same time, grid users would benefit as well, due to a quicker and less expensive satisfaction of the identified system needs.[5] In addition, the new solution would, over time, become the ‘new’ traditional solution, with its further implementation not deserving the incentive in the following regulatory rounds.

Of course, the proposed scheme may not be adequate for stimulating every type of innovation. For instance, it will probably not be the best tool to promote the deployment of innovations that are at a very low level of technological readiness, due to the high uncertainty about the associated costs and results. Other mechanisms would perhaps work better in this case. The proposed scheme is also likely to present some implementation challenges, such as the identification of the traditional solution to a system need and the estimation of its cost, but they do not look very different from the challenges that characterise the implementation of any incentive scheme applied to a dynamic context.

If the problem is represented by cash-strapped regulators, the solution is probably not to give up, but rather to put regulators in the position to implement well-designed incentive schemes that align the interests of system operators with the needs of a rapidly changing electricity system. This means ensuring regulators have a skilled and experienced staff that can minimise the information asymmetry with the regulated entities and constructively ‘challenge’ them. In the usual times we live in, this seems to be a high-return investment to the benefit of energy consumers and the energy transition as a whole.

The issues addressed in this blog post will be part of the conversation in the FSR Policy Workshop on Energy networks for the green transition that will take place in Brussels on 3 October 2025.

[1] The expressions ‘grid-enhancing technologies’ (GETs) and ‘innovative grid technologies’ (IGTs) are often used to refer to this broad set of technologies.

[2] It is important to note that developments in technology are likely to reduce the need for investment in grid-related physical assets, but they are likely to be far from sufficient to ensure the satisfaction of the increasing system needs triggered by the energy transition in Europe. The report issued by Compass Lexecon in 2024 suggests that IGTs can increase grid capacity of an existing network by 20-40% and reduce grid expansion costs by 35% by 2040. However, in some cases, such as offshore, new lines will have to be built to connect new generation or load facilities. And in others, efficiency increase due to IGTs will not be enough: iron and copper additions will be necessary. See Compass Lexecon (2024), Prospects for innovative grid technologies – Final Report, 17 June 2024, available at: https://www.currenteurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CL-CurrENT-BE-Prospects-for-Innovative-Grid-Technologies-final-report-20240617-2.pdf.

[3] In the European Union, system operators are normally the entities that own and operate the grid. Therefore, in this blog post, system operators and network companies can be considered synonyms. This is not the case in other jurisdictions, where independent system operators exist, such as Great Britain or most of the liberalised electricity markets in North America.

[4] An early version of the scheme was presented at the Copenhagen Forum of Energy Infrastructure in June 2023 (slides available here) and described in a research note published on the ACER website (note available here). The final report of the study was presented in Brussels in June 2024. The recording of the presentation is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSf28Spu2us.

[5] The technical identification of the system needs can involve system operators and benefits from their superior knowledge. However, it is the regulator that at a certain point has to stick its neck out and sanction the satisfaction of such needs into the network development plan.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights