Regulatory sandboxes in the energy sector – the what, the who and the how

What are regulatory sandboxes in the energy sector? Let's find out analysing the cases of the Netherlands and Great Britain.

Defining Energy Regulatory Sandboxes

The idea behind a sandbox finds its origin in software engineering: a sandbox – as in a testing environment – for running potentially unsafe codes, without the risk of infecting the entire system. A regulatory sandbox is not unique to the energy sector and has previously been introduced in other sectors such as banking and healthcare. Actually, in a recent paper about Fintech regulation I found one of the best descriptions of what a regulatory sandbox is:

’’A good starting point of what the principle of a sandbox is can be derived from its name: a safe playground in which to experiment, collect experiences and play without having to face the strict rules of the “real world”. Whereas the sand of an actual sandbox protects against harm while playing, certain consumer safeguards are established to fulfil that task in its regulatory counterpart. Meanwhile clear entry and exit requirements, as well as a pre-defined scope, display the borders of the box.’’

The motivation behind setting up a regulatory sandbox is two-fold. First, allow innovators to test new technologies and business models that are only partially compatible with the existing legal and regulatory framework. Second, allow regulators to learn about particular innovations. As such, regulators can develop the right regulatory environment to accommodate them.

Who has them?

In the energy sector, the use of regulatory sandboxes is quite new. The ISGAN Casebook on Innovative Regulatory Approaches with Focus on Experimental Sandboxes and a recent White Paper of the Vlerick Energy Centre cover several case studies in Australia, Austria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Great Britain and the United States. At present, the Netherlands and Great Britain have gained specific and extensive experience with a sandbox-like approach to energy at the time of writing. In this short piece, I focus on these two.

First, in the Netherlands, instead of waiting for a new Gas and Electricity Act, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs issued an executive order ‘Experiments Decentralized, Sustainable Electricity Production’ (EDSEP) that entered into force in 2015. The admission started in 2015 and ended in 2018. Over that four- year period, 18 projects were initially awarded a sandbox, 15 of which are still active. I did not find any information about how many projects that did apply. What I did find is that a cap of 20 projects per year was set to control the administrative burden.

Second, in Great Britain, Ofgem launched the regulatory sandbox initiative in December 2016 via its Innovation Link Program. So far, Ofgem has run two application ‘windows’, one in February 2017 and another one in October 2017. Out of these two calls, seven projects were awarded a regulatory sandbox out of 67 applicants. Interestingly, the rather low number of awarded sandboxes is not due to many innovators asking for unreasonable derogations. Instead, after discussions with Ofgem, many innovators found out that they could go ahead without the need for a sandbox.

📢 Keep up with the energy sector with our new in-depth analyses #researchbites 📚- In the first one we tackled “the what, the who and the how of #regulatorysandboxes in the energy sector” Find out more in @SchTim1 podcast and articlehttps://t.co/vTLYva5IwA pic.twitter.com/28XcdBhIFu

— FSR Energy (@FSR_Energy) April 16, 2020

How are they used?

Similarities and differences between the first regulatory sandboxes in NL and GB

An important similarity between both country cases is that currently awarded projects are developed at electricity retail-level. Typical projects applying for a regulatory sandbox are focused on matching local (renewable) generation and demand through innovative retail tariffs or peer-to-peer trading. The energy can be generated through new types of arrangements such as energy communities that possibly own the last mile of the distribution network.

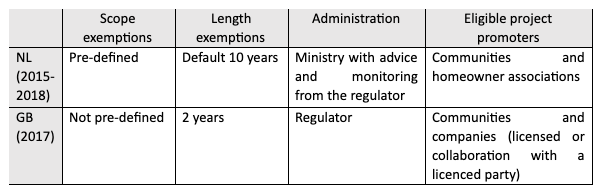

Important differences in the implementation of regulatory sandboxes between the two countries are shown in the table below.

- First, in the Netherlands, the articles in the Electricity Act from which projects could be exempt from were pre-defined – a sort of “menu” approach. In Great Britain, the particular exemptions were not pre-defined but identified by the innovators jointly with the regulator – more “à la carte”.

- Second, the duration for which the exemptions were given differs substantially, from rather short in Great Britain (2 years) to rather long in the Netherlands (10 years)

- Third, in the Netherlands, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate is in charge of the sandbox design and admission process. In Great Britain, it is the regulator.

- Fourth, the regulatory sandboxes in the Netherlands were explicitly reserved for new small players in the energy scene: energy communities and homeowner associations. In contrast, in Great Britain project promotors were not strictly defined; they varied from energy communities such as the Chase Solar Community to established international players such as BP and EDF and national suppliers such as OVO Energy.

The future of regulatory sandboxes in NL, GB and other EU countries

In both country cases, these first experiences with regulatory sandboxes were overall considered positive. The initiatives quickly expanded and evolved according to the gathered learnings.

In the Netherlands, currently, a follow-up executive order is being proposed that expands the size and scope of projects that can enter the sandbox. Importantly, also pre-defined exemptions under the Gas Act will be possible. Also, more traditional players such as DSOs and energy suppliers will be allowed to apply. Examples of activities that fall under the scope of the new decree are running a local flexibility market and new business models for aggregators.

In the case of Great Britain, Ofgem published six insights from running the first two calls for regulatory sandboxes. These learnings informed a reform of the sandbox approach itself. Similarly as in the Netherlands, the scope of the sandbox was expanded by increasing the number of rules and codes that Ofgem can provide relief from. Another significant change is that unlike the original sandbox, innovators will be able to access the service when they need it rather than only during strict windows deadlines.

Both countries are expected to open the ‘’Regulatory Sandboxes 2.0’’ later this year. Soon, we will see more regulatory sandboxes appear in many other EU countries such as France (Bac à sable réglementaire), Austria (Energie.Frei.Raum) and Germany (7th Energy Research Programme).

_

Interested in knowing more? Please register for our online debate on 3 February 2021 at 2:00 PM CET – “The Regulation of Power-to-Gas Facilities and Regulatory Sandboxes”.

_

Read more: WORKING PAPER | Regulatory Experimentation in Energy: Three Pioneer Countries and lessons for the Green Transition by Tim Schittekatte, Leonardo Meeus, Tooraj Jamasb, Manuel Llorca.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights