New challenges for DSOs in the energy transition

Highlights from the event "The new role of distribution system operators"

On October 25th 2023, FSR hosted the FSR Debate “The new role of distribution system operators” (DSOs). The panelists discussed the multiple challenges that DSOs will face in the context of the energy transition (more grid investments, increased network planning and forecasting of new technologies), as well as the operational and regulatory implications of such challenges.

Why is the energy transition changing DSOs role in the electricity system?

Electricity will become the dominant energy carrier, with electricity consumption expected to double in Europe over the coming decades. The energy transition represents a real change of paradigm at the distribution level, and DSOs are expected to become the “backbone” of the electricity system, according to Carmen Gimeno (GEODE). On the demand side, electrification implies new types of loads such as electric vehicles and heat pumps, which will significantly impact consumption levels and profiles at the distribution level. On the supply side, the electricity system will rely on a dominant share of solar PV and wind, which are largely connected at the distribution level. This implies naturally an increasing use of distribution grids, and, more specifically, a bi-directional operation of those grids that were historically driving electricity from the transmission level to the consumers’ level. Moreover, Gert De Block (CEDEC) pointed out the evident challenge that weather conditions will define the supply and impact the demand, increasing the volatility and stochastic nature of flows in distribution grids.

The combination of these changes represents a huge challenge for DSOs. They will have first to develop and expand their grid, second to unlock and manage flexibility, and third to increase coordination with TSOs as well as with other sectors.

First challenge: grid investments

The first challenge that DSOs face is the significant grid development required in the longer term. It is estimated that annual investments in distribution grids should increase from 50% to 70% over the period 2020-2030 (Eurelectric and E.DSO, 2021). To be able to connect renewables and new loads, grids need to be significantly expanded and reinforced. Louise Rullaud (Eurelectric) mentioned that we need to double the number of additional connections to the grid to achieve decarbonization, because we are quickly consuming the capacity that was built in the past. Today we see scarce capacity in The Netherlands, but also in Spain, Germany and Ireland. Mrs Gimeno specified that grid expansion is not only about acting upon connection requests but anticipating future grid needs, in order to invest in a timely manner.

In fact, while in the current policy and regulatory scenario, a lot of emphasis is put on the development of renewables and flexibility solutions, the transition cannot happen without a grid fit for purpose. Therefore, grid investments should have more room in the discussion and require an evolution of the historical regulatory approach. Regulation used to play a key role for the evaluation of investment costs, but this cannot account for future needs and answer the investment challenge that DSOs face today, according to Mr De Block. Mrs Gimeno proposed that the regulatory approach could partly evolve following the Market reform proposal, which includes more balance between CAPEX and OPEX, as well as a new concept of anticipatory investments.

Moreover, grids will need to be modernized. Distribution grids are still relatively “blind”. Much more observability and controllability will be required to properly manage the future system. This requires DSOs to provide massive investments in digitalization, according to Mrs Rullaud. Three tools are then mentioned for this optimization and modernization of grids:

- Local flexibility markets;

- Network tariffs. Time of use tariffs seem a very efficient tool to support grid management;

- Flexible connection agreements. They should be deployed in all Member States in a voluntary way, but also, at first instance, temporary.

To allow grid modernization, smart meters deployment is essential. At the consumers’ level, it is ongoing, but it is heterogeneous across Europe and still insufficient. DSOs are not as advanced as TSOs regarding digitalization, despite it being, according to Mr De Block, a condicio sine qua non for active management and flexibility services. Digitalization is a challenge that comes naturally with data management and exchange, gathering inputs from millions of devices and it is a challenge of a different scale and nature for DSOs, who operate millions of individual consumption points. Cooperation is currently ongoing on the standardization and interoperability of tools and platforms, highlighted Fabio Genoese (ENTSO-E).

In addition to digitalization, specified Roberto Zangrandi (E.DSO), technological developments represent a key issue for the role DSOs will have to play. New technologies and their implications must be tackled not when already available, but in advance. They must be imagined and forecasted years before they enter the market. For this purpose, E.DSO for Smart Grids published a tool called Technology Radar. It is the result of a Working Group that mapped the technologies which will develop in the next years and which will affect DSOs activities: these technologies are divided considering their impact on DSOs tasks and their timeline of development. Early identification of new technologies and technological trends can prevent painful disruptions of models and also of financial and economic viability of DSOs. For the same purpose, in October 2023, the European Commission (EC) published a series of recommendations on the risk assessment of four critical technology areas: advanced semiconductors, artificial intelligence (AI), quantum and biotechnologies. Under AI, the EC lists, among others, high performance computing and data analytics. These technologies are already being used and they will be essential for DSOs; if we have the ability to correctly forecast and have the right perspective concerning technology in the DSOs business, there will be a brand new chapter of operational efficiency analysis of system operators.

Expansion and modernization of the grid cannot happen without investments in skilled workforce. Mrs Rullaud affirmed that DSOs will need to hire more than 500 thousand people to update the grid, speeding up capacity buildout to host the revolution brought by renewables. Additionally, permitting issues must be addressed. The average waiting time for distribution grids permitting is one year, which goes from five to ten years for transmission grids. Therefore, we need to strive for a modern EU mandate for regulators to best incentivise the efficiency of grid capacity buildout. There can be two ways to do it:

- Allowing in the regulatory framework more forward looking planning and investments;

- Streamlining grid permitting.

Second challenge: unlocking the required flexibility

While significant grid investments are inevitable, there are opportunities to avoid costs and over-investments by unlocking local flexibility. Reducing congestion and peak use of distribution networks concerns both the demand side, which can reduce and shift consumption, as well as the supply side through renewable curtailment. In particular, the rollout of EVs and heat pumps could represent a huge potential for flexibility procurement, with at least around 100GW available by 2030 stated Mr Genoese.

There are many different possible options to source and manage local flexibility, from distribution tariffs to flexibility markets. The solutions can be either DSO-initiated or market-based, and either reactive or preventive, and their design and regulatory framework is still quite open. Already in 2018 and 2019, CEER and the TSO-DSO associations produced two reports with a taxonomy of these solutions, the so-called “flexibility toolbox”. More discussions are currently ongoing with the new demand-side network code development.

We now go more in depth into these solutions. The first one consists of distribution network tariffs, which relied historically mostly on energy-based components. Net metering meant that PV owners could reduce their grid tariff component, while still relying on a significant grid capacity. This leads inter alia to a gradual integration of capacity-based components. There is an opportunity to keep making network tariffs more dynamic to provide better signals to system users. However, network tariffs will always be imperfect, and depend on the voluntary response of consumers, pointed out Ellen Beckstedde (EUI). Therefore, we will need to rely on other solutions as well.

The second tool will be the explicit and market-based procurement of flexibility, through the so-called flexibility markets. There are pioneers such as Piclo, NODES, GoPacs and Enera that have emerged in the last decade (Beckstedde and Meeus, 2023). The diversity of these pioneer solutions shows that there are numerous design choices possible. Which design is optimal is still an open question. These markets are expanding but are still limited in terms of traded volume. They need to become more mature. However, their success depends on the interest of consumers in providing flexibility services, which, according to Mr De Block, is still uncertain.

The third tool is flexible connection agreements. While it was not in the Clean Energy Package, a framework for flexible connection agreements is foreseen in the Electricity Market design proposal. They would become a temporary congestion management tool to connect grid users in highly congested areas. Research shows that the pricing of such agreements is not straightforward when a grid hosts both passive consumers and active prosumers (Noucier, Meeus and Delarue, 2020). Non-firm connection agreements are already foreseen in the Netherlands, where the grid is under high pressure at all voltage levels.

Third challenge: enhanced cooperation

Mr Genoese stated that we are going towards a system of systems, both more European and more local. More local with more responsibilities arising for DSOs, and more European as we will shift more energy from one area to another. This system of systems will require more cooperation between DSOs and TSOs as well as other actors, at the European level, and cross-sectoral level.

One could say that, historically, TSOs were used to a “big brother behavior” towards DSOs and now this will have to change. It will imply real same-level agreements, e.g., more intentional network codes and a better inclusion in the Ten-Year Network Development Plan, affirmed Mr De Block. While the role of DSOs is being more and more reinforced, there may be room for improvement.

TSOs-DSOs cooperation is notably ongoing between ENTSO-E and the EU DSO Entity. They have identified four strategic areas for cooperation. First, cooperation is needed to unlock flexibility, coordinate its use, and define the capabilities of future grid users. Second, grid operators will need more observability and controllability in operations, through standardized and interoperable tools and platforms. Coordinated congestion management and voltage control will also be required. Third, coordination will be key in the planning and scenario development for infrastructure and investments. This notably concerns the design of access procedures and connection agreements. Fourth, TSOs-DSOs cooperation is necessary for consumers’ empowerment, e.g., to develop the right measurement devices, reported Mr Genoese. Today, ENTSO-E and the EU-DSO entity are developing in close cooperation the new network code on demand response.

Finally, we need to broaden our perspective of flexibility beyond demand response, notably to include cross-sector integration, according to Mr De Block. The gas, hydrogen, and district heating sectors could provide significant flexibility, including long-term and seasonal flexibility. The “silo” thinking is still too present. Closer cross-sectoral cooperation will be needed to optimize network planning and to unlock all types of flexibility.

Polls

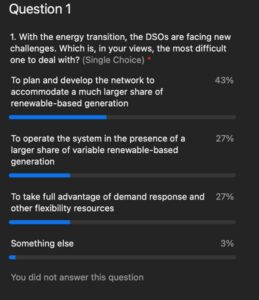

The three polls on DSOs activities and their regulatory framework were then proposed to the audience.

The first poll, concerning the most difficult challenge DSOs must deal with in the context of the energy transition, resulted in a slight majority of the audience opting for the physical development of the network. Mrs Rullaud confirmed this choice, emphasising that the real challenge consists in investments in the grids. Looking at the past decade, the energy sector has constantly underestimated investment needs: it did too little too late and this must change, according to Mr Genoese. Moreover, not being able to properly plan and develop the network and, therefore, not having the conditions to operate flexibility tools, represents a hurdle for DSOs when contributing to the energy transition. The crucial role of planning is underlined also by Mrs Gimeno. Proper network planning is a key tool to prepare grids for new challenges and make them more resilient. In this context, actions relating to the digital twins (decarbonisation and digitalisation) are relevant for DSOs, to allow them to exploit digital tools for more efficient grid operation.

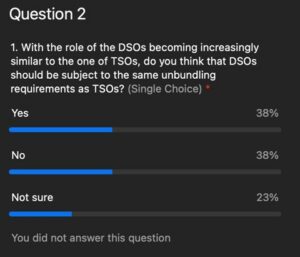

The second poll, questioning the extension of the same unbundling requirements of TSOs to DSOs, given the increasing similarity of their role, saw a mixed reply. Mrs Rullaud rejected

the possibility of this extension of stronger unbundling to DSOs, stating that the impacts on the markets of DSOs activities are limited and the current regulatory framework provides flexibility for businesses in local areas. Mrs Gimeno confirmed that ownership unbundling for DSOs is not necessary in light of the differences between TSOs and DSOs and also considering DSOs position in the market and their capacities: stronger unbundling requirements will put at risk the economic viability of DSOs activities. Mr De Block added that there seem to be no issue relating to the current unbundling regime (which has been set up not to impose excessive costs on entities of small scale) and the change proposed in the poll would lead to reduced competition in the market.

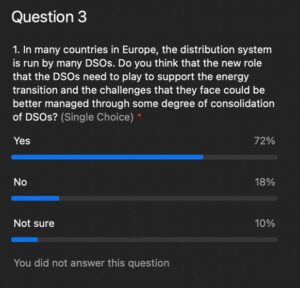

The last poll investigated the possibility of consolidation of DSOs in order to better manage their new role and the audience emerged as in favour of this option. In Sweden, for example, the attempt to consolidate is being carried out for scalability reasons, Mrs Rullaud mentioned, but other aspects must be considered in addition to size, like shareholding and tasks performed: consolidating does not seem an easy option. According to Mrs Gimeno, there is no need to impose consolidation or to go for it. After the liberalisation of energy markets, many DSOs emerged; this decentralisation allows the local dimension to become more and more important. For example, Mr De Block affirmed that, in a decentralized energy system, there is better awareness of local opportunities for projects concerning renewable sources. However, decentralization calls for more cooperation between DSOs at the national level.

At the end of the session, Alberto Pototschnig (FSR) asked the panellists their view on the role of prices to manage the challenges for DSOs which emerged during the debate. Mr DeBlock highlighted the role of connections and, more specifically, the interest of customers in peak load pricing, on the condition that such customers have a load they can manage: moreover, this possibility must be balanced with the costs of having every connection able to perform such load management. Mrs Gimeno highlighted that tariffs must provide incentives and signals to consumers, allowing them to efficiently use the grid and, at the same time, to benefit from new opportunities and savings. Furthermore, profiling the customer, stated Mr Zangrandi, can expand retail offers for him/her. According to Mrs Rullaud, a case-by-case assessment by DSOs is needed to evaluate the most cost-efficient solutions, which, in some cases, can be time-of-use tariffs or flexible connection agreements, in other cases it can be capacity buildout. The key point is to enable DSOs to have all the alternatives to set appropriate remuneration schemes, which are necessary to unlock flexibility solutions. Moreover, considering the massive investment needs for new capacity, one could reimagine the asset-based tariff; this kind of tariff, according to Mr Zangrandi, is no longer adequate to face the next developments of DSOs and the paths of new technologies. It is time to start thinking about modernising the tariff structure in a non-disruptive way.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights