Mind the gap: the proposed governance of the Energy Union

Written by Marie Vandendriessche

This Topic of the Month will zoom in on the EU’s Energy Union, and particularly a novel part of it: the Governance regulation proposed by the Commission in November 2016, which is currently travelling along the legislative pipeline. After last week’s post on the birth of the Energy Union, in this post, we will focus on how the Commission proposed to ensure policy coherence, complementarity and ambition in this new structure: through a regulation on Governance.

Why the need for Governance?

As discussed in the previous post, a combination of three factors explains the need for this very new element in the EU’s energy policy: (1) the interconnected and holistic nature of the new Energy Union itself, (2) the requirements for the EU and its member states under the UNFCCC’s Paris process, and (3) the 2020/2030 switch. When the EU set its energy and climate targets for 2030, it largely abandoned the approach of nationally binding objectives, shifting to EU-level targets instead – and thus created some important multi-level challenges.

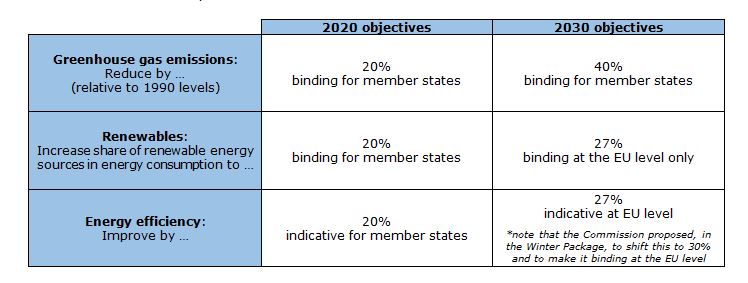

The 2020 energy and climate targets were relatively simple in their structure: the goals on reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and increasing the share of renewables in energy consumption were binding at the member state level, while the energy efficiency goal was indicative at the member state level. It is important to place these targets in their context: they were set in 2007-8, before the effects of the global economic crisis truly started to damage confidence in the European project, and before COP15, the critical climate change summit held in Copenhagen in 2009 in which the EU hoped to play a leading role (although this hope did not become reality).

The sequel to this framework – the 2030 energy and climate targets – was proposed and approved in 2014. However, the times had changed. Again, an important climate change summit – the COP21 summit in Paris – was right around the corner. And again, the EU wanted to take a leadership role in climate change mitigation. However, experiences with the implementation of the 2020 targets and the confidence-eroding effects of the crises led European leaders to choose a different design for the 2030 objectives. While the GHG reduction target remained binding at the member state level, the targets for energy efficiency and renewables were set at the Union level only.

The question thus emerged: How could it be guaranteed that the member states’ individual contributions would add up to reach the collective, Union-level renewables and energy efficiency goals? A clear framework would be required – and this is where governance came in.

What type of Governance? The proposed design.

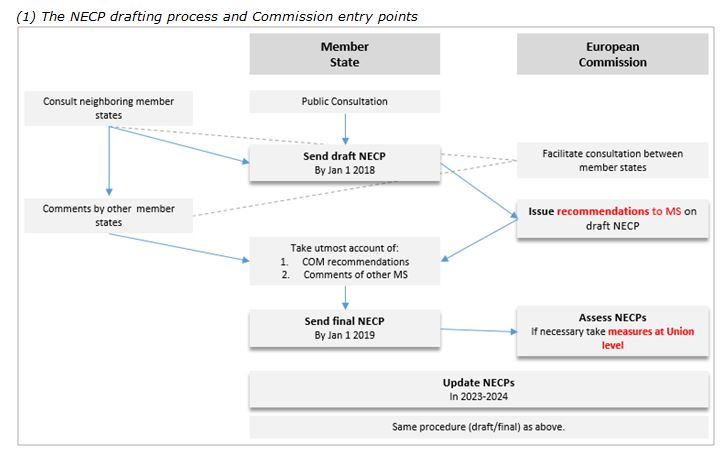

The Commission proposed, in November 2016, a Governance regulation with two main building blocks: (1) ten-yearly national integrated energy and climate plans (NECPs), and (2) a reporting and monitoring process (consisting chiefly of biennial progress reports and a set of specific provisions for GHG emissions inventories).

Each EU member state would be required, in 2018-2019, to draw up a national plan for the 2020-2030 period, revealing the fit of its planned policies and measures with the overall 2030 and Energy Union goals. This drafting process, depicted graphically below, would allow the Commission to detect any gap in member states’ ambition (with respect to the Energy Union/2030 goals).

From 2021 on, member states would be required to submit biennial progress reports on the implementation of their national plans. The reports would allow the Commission to discover any gap in delivery – whether at member state level (if a country was not living up to its national plan) or Union level (if the member states’ efforts were not adding up the collective goal) – and take measures to fill those gaps. These procedures are represented and described below.

For the GHG target, which has remained nationally binding in the 2030 framework, the proposed Governance regulation largely encapsulates previous legislation on reporting, monitoring and verification (which has been honed over the years through EU and member state experience with the Kyoto Protocol). In terms of planning, member states are required to include their GHG policies in the national plans (NECPs). In addition, they must develop long-term low emissions strategies with a 50-year perspective (in keeping with the EU target of reducing the Union’s GHG emissions by 85-90% by 2050).

What tools? The power under the hood.

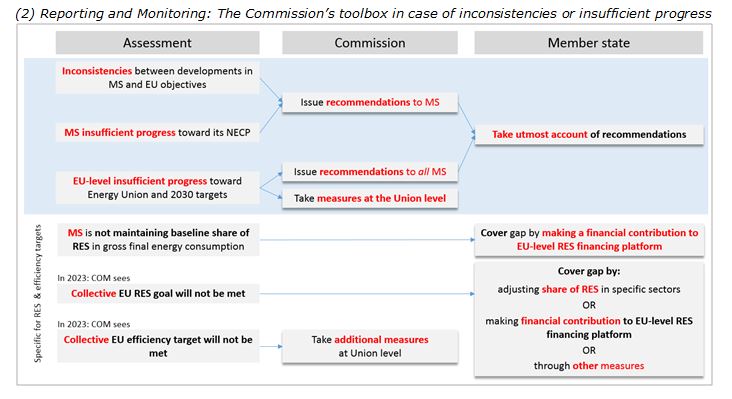

As represented above, both elements of the Governance regulation – NECPs and progress reports – provide entry points for the Commission to detect problems (of consistency, coherence or ambition) and deploy tools to address them. The potential power of each of these tools – which are utilized in specific circumstances, see figures above – is discussed in turn:

- Union-level measures: If the Commission detects ambition gaps or gaps in the execution of NECPs, it can take measures at the EU level as a remedy. Since the proposed regulation does not offer further detail on what shape these measures might take, this remains open to the imagination. Creating and taking EU-level measures, however, involves potentially fraught political processes – which might limit their ultimate strength and effectiveness.

- Commission recommendations to member states: The effectiveness of this measure depends almost entirely on the goodwill of the member states, given that no explicit backstops are foreseen in case these indicative recommendations are not implemented. Past experiences have shown that application of such recommendations has been limited.

- Specific gap-closing measures for the renewables and energy efficiency goals (see the bottom section of figure above): These tools are more concrete, which could also make them a more contentious element in the legislative process on the regulation. Regarding the financing platform (which is proposed as a gap-filling mechanism in case the collective Union-level renewables goal appears unlikely to be met), there is little clarity on its functioning. In general, if these tools were to be used, it is likely that the Commission would seek technical solutions through committees, only reaching the Council in case no agreement were reached.

Overall, it is clear that while the proposed reporting and monitoring system is strong on formal processes and procedures, it is very much open-ended on substance, and particularly on enforcement rules. The governance of the GHG target, which has remained nationally binding, is the exception.

- Specific gap-closing measures for the GHG goal: Not represented in the figures above, the GHG-related tools include remedial action plans, opinions and recommendations; as well as compliance checks and potential changes to emissions allocations (described in more detail here). In general, these measures have more bite, which may increase their effectiveness.

- Transparency: although this is perhaps not an explicit governance tool, the transparency provided by the public NECPs and the monitoring and reporting process (which also includes yearly State of the Energy Union reports) opens up multiple vantage points from which all types of actors can study both member state and overall EU progress towards the 2030 and Energy Union targets. This could open the door for ‘naming and shaming’ type processes.

In general, and despite some clear corrective measures for the GHG target, many of the tools proposed in the new regulation could be labelled ‘soft governance’, in which reputational mechanisms play a large role. In other words, in this model, the goodwill of member states would be vital to bridge the national/EU-level gap that was created when the 2030 goals were set.

But both the regulation and its tools are yet to be confirmed, as the legislative process on the proposal is still underway. The political debate on this regulation will be the topic of the next – and final – post.

References

Adolf, C. & Nix, J. (2016). The effectiveness of the European semester from a governance perspective. Retrieved from Green Budget Europe website: http://green-budget.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016-04-27-GBE-Semester-Governance-Final.pdf

European Commission. (2016). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and to the Council on the governance of the Energy Union, amending Directive 94/22/EC, Directive 98/70/EC, Directive 2009/31/EC, Regulation (EC) No 663/2009, Regulation (EC) No 715/2009, Directive 2009/73/EC, Council Directive 2009/119/EC, Directive 2010/31/EU, Directive 2012/27/EU, Directive 2013/30/EU and Council Directive (EU) 2015/652 and repealing Regulation (EU) No 525/2013. (2016/0375(COD)). Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1485940096716&uri=CELEX:52016PC0759

Vandendriessche, M., Saz-Carranza, A. & Glachant, J.-M. (2017). The Governance of the EU’s Energy Union: Bridging the Gap? [Working paper]. Retrieved from European University Institute website: http://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/48325

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights