From waste to a waste-to-energy model in Nepal

By creating an effective waste management program, Clean City works to protect the environment, create financial stability at the local level by creating viable jobs and stimulating the local economy, and empower the most marginalized groups in the local community.

Clean City is a social enterprise and grassroots organisation that aims to radically shift the paradigm from waste to waste-to-energy, focusing its work on protecting the environment, addressing plastic pollution and providing education and employment in Chitwan, Nepal. Founded by Taylor Smythe, along with an inspiring group of local change-makers, Clean City seeks to create a comprehensive community-based approach to waste management, which can be replicated in other parts of Nepal and the global south.

We sat down with Smythe to understand how their organisation came to be, how the locals contributed to the success of the initiative, and how Nepal sets an example for other communities to replicate.

From start-up to social enterprise

After a 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked Nepal’s capital Kathmandu and its surrounding areas in 2015, Smythe flew in the country to work as a Project Manager on a Disaster Relief (DR) project. There she was presented with a grim picture: the main quake and the aftershocks had killed nearly 9,000 people and injured many more, over 600000 buildings were either heavily damaged or destroyed, entire communities were displaced.

Despite the earthquake weighing enormously on the economy of the region, Smythe soon came to notice that the natural disaster wasn’t the only pressing problem afflicting Kathmandu Valley:

I realised the overwhelming amount of pollution that could be seen everywhere and felt compelled to seek out solutions. With 70 per cent of Nepal’s waste being dumped or openly incinerated, the lack of waste management poses a major environmental crisis and human health hazard.

As she stepped away from relief services, Smythe became convinced that the only way to create systemic change was to empower, educate, and employ local people by providing the necessary skills and resources to address the root of the people’s underlying problems.

While in search of ways to contribute, Smythe got in touch with Kalpavriksha Greater Goods’ CEO, Sita Adhikari. Kalpavriksha Greater Goods is an energy distribution network that empowers and employs more than 350 women from marginalised communities across remote parts of Nepal:

After only one meeting, Sita and I immediately connected and realised we shared the same vision for using business to expand social, economic and environmental impacts for women in Nepal. One week later, I travelled to Sita’s village where she introduced me to her husband, Bashu Dhugana, a local politician, community leader and the president of a sustainable waste management cooperative comprised of 120 local business owners operating in the tourism industry outside Chitwan National Park in the Terai region. Realising the devastating impacts of pollution and immense threats to the wildlife, environment and surrounding villages, together we founded Clean City.

Clean City is a community-driven, self-sustaining social enterprise that employs a predominantly female taskforce and engages informal waste collectors to implement waste management solutions, specifically at-source waste segregation, recycling and upcycling, composting in households, schools and businesses and providing alternatives to single-use waste.

By creating a grassroots initiative, Smythe and her business associates and mentors, Sita Adhikari and Bashu Dhugana sought to change that endless cycle of financial dependency on foreign aid experienced by the Nepalese communities:

Nearly 50,000 registered non-governmental organisations are working in Nepal, many of which depend heavily on donors or external funding from international aid agencies, which is not sustainable and contributes to a local economy reliant on handouts and a continuous cash flow from Western countries.

Alternatively, Clean City’s waste management program aims not only at protecting the environment but also at creating financial stability at the local level by providing viable jobs and stimulating the local economy, whilst also empowering disadvantaged women in the local community:

We realise that change doesn’t come overnight. It requires a team of people with patience and dedication to purpose. From the beginning, our operations manager, Sushila Dhamala, and education coordinator, Maila Ghale, have been working tirelessly to educate students, citizens and society leaders about the importance of proper waste management. We strengthened community ties through our partnership with the local municipality and Digo Fohor Bebasthapan Sahakari (Nepali for Sustainable Waste Management Cooperative ), which facilitated cross-sector collaboration and galvanised influential community leaders, including Nepal’s first female nature guide and conservationist, Doma Paudel, and Sapana Village Social Impact’s founder, Durbha Giri. The local community is the backbone of Clean City, and without their patience, persistence and commitment to our shared vision, we would not be where we are today.

Waste-to-energy model

Clean City’s innovative model puts waste at the centre of their plan for economic growth and search for sustainable solutions:

At Clean City, we believe the best solution is to radically shift the paradigm from waste to waste-to-energy. We need to move away from our current take-make-waste extractive industrial model to a circular economy where we rethink and redesign products and components and the packaging they come in so that they retain their value and the waste from today can be used as a resource for tomorrow. We need to treat waste as a resource, which will, in turn, spark innovation. We are aiming to eliminate linear waste streams to responsible waste management systems where useful resources are retained, refurbished, reused and recycled. If segregated at source, we can reduce what waste ends up in landfills by 90%. We believe waste segregation is critical to a sustainable future.

We need to move away from our current take-make-waste extractive industrial model to a circular economy where we rethink and redesign products, as well as their components and packaging so that today's waste can be used as tomorrow's resource.

Civic participation, community ownership and building on existing cultural values are crucial to the long-term success and sustainability of this project.

Civic participation, community ownership and building on existing cultural values are crucial to the long-term success and sustainability of this project – Smythe insists. She also believes that, whereas the West has sought sustainable solutions as a response to human-caused climate issues, for the Nepalese people sustainability has been a way of life for thousands of years:

Local communities have a wealth of knowledge and understanding about their region, available resources, traditional methods, which are rooted in sustainability and functionality.

People often talk about social enterprise and sustainability as new things that Nepal needs to learn from the West. Historically, Nepal has a story of sustainability that is deeply ingrained in its culture. It is a nation built on people living in harmony with nature and close connection with the Himalayas. In many ways, the country has a much deeper and more meaningful story about sustainability [than the West], which is intricately woven into the fabric of its society and culture.

[modula id=”28754″]

Nepal’s history and relationship with sustainability also has the potential to set an example for other countries and communities. And Smythe certainly plans to export this bulk of knowledge elsewhere for other communities to profit from the Nepalese experience:

I am currently working in Sri Lanka, where I am researching the potential for setting up a small pilot project in a local community on the northwest coast to recycle discarded fishing gear. Fishing gear makes up nearly 46% of all marine litter in our oceans. An estimated 640,000 tons of fishing gear are dumped in the ocean each year, polluting the sea and fatally trapping marine life. The northwest coast is particularly affected, because the pollution from India’s fisheries damages their coastline, marine life and ecosystems. The fishing industry plays a vital role in Sri Lanka’s economy, and a large demographic of the labour force is at risk due to increasing marine pollution, overfishing, and the effects of climate change.

I am currently in the process of interviewing locals and connecting with other local organisations who are taking the initiative to address waste management across Sri Lanka. I am conducting a feasibility assessment to see the potential for upcycling the fishing nets into products to be sold back in Sri Lankan communities, establishing a line of employment for locals that could be expanded on in the future.

Clean City and Women’s empowerment

As the daughter of two Marine Corps Colonels, Smythe grew up in a household with two brothers where gender equality was a value instilled in me from an early age. When she started travelling independently, she witnessed firsthand the enormous gaps in the basic rights and access to educational and economic opportunities between men and women and that achieving gender equality:

Amidst the global pandemic today, millions of people lack access to basic needs, like food, water and shelter, and unfortunately, the vast majority of people that are being disproportionately affected are women. However, we are also witnessing a growing trend in strong female leaders emerging at the local, regional and international levels. We can see the values of a society reflected in its budget–how the governing bodies choose to allocate their resources. It is no surprise that countries where there is a greater equal distribution of power among men and women, tend to invest more in improving women’s education, reproductive roles, access to healthcare and birth control, adequate nutrition–all of which contribute to improved livelihoods, healthy communities and resilient, local economies.

[modula id=”28748″]

Addressing gender inequalities is at the core of the Clean City mission. Clean city leveraged Nepalese local values and talent to create new streams of income, turn the waste problem around, and empower its people.

Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world, with more than 25 percent of the population living below the poverty line. Today, more than 50 percent of the Nepalese population is unemployed. Women comprise 75 percent of the unemployed, leaving women and their children at severe risk of slavery, prostitution, and human trafficking. In Nepal, it is not uncommon to see women well into their seventies carrying enormous loads weighing upwards of 75 lbs on their back. Women are responsible for all the day-to-day household chores and unpaid labor activities, such as subsistence farming or caring for livestock. Patriarchal attitudes and gender norms within Nepali society create even more difficulty with regards to women’s access to education, economic, and political resources. Poverty and food insecurity within the country contribute to illegal child marriages. 37 percent of girls in Nepal are married before 18 and 10 percent are married by age 15. Families that do not have enough food to eat are more likely to marry their daughters at a young age to reduce their financial burden.

Where many see a problem, Clean City saw an opportunity. And the spillover effects from empowering the local community and its women have been enormous and are among her proudest accomplishments. Clean City focuses on empowering, educating, and employing disadvantaged and marginalized women, with women most affected by social injustice and poverty constituting at least 70% of their staff. By providing vocational training, we are helping women gain control of their lives and become financially independent members of society.

Learn more about Clean City Global

About Taylor Smythe

Taylor Smythe is currently a Cocreator at Good Market, a curated community that connects social enterprises and voluntary initiatives that are good for people and good for the planet. She is responsible for curation, community building, and networking. Before joining the Good Market team, Taylor spent four years in Nepal and founded Clean City, a social enterprise aimed at tackling waste management challenges and creating community-driven solutions. She is passionate about women’s empowerment, sustainable development and systems thinking.

“We are all inextricably connected in the web of life. Every individual has the power to make conscious decisions creating ripples, which will lead to a more sustainable world for future generations. Never underestimate our potential to be agents of positive change. Now is the time to act, inspire and empower others to do the same.”

Related Initiatives:

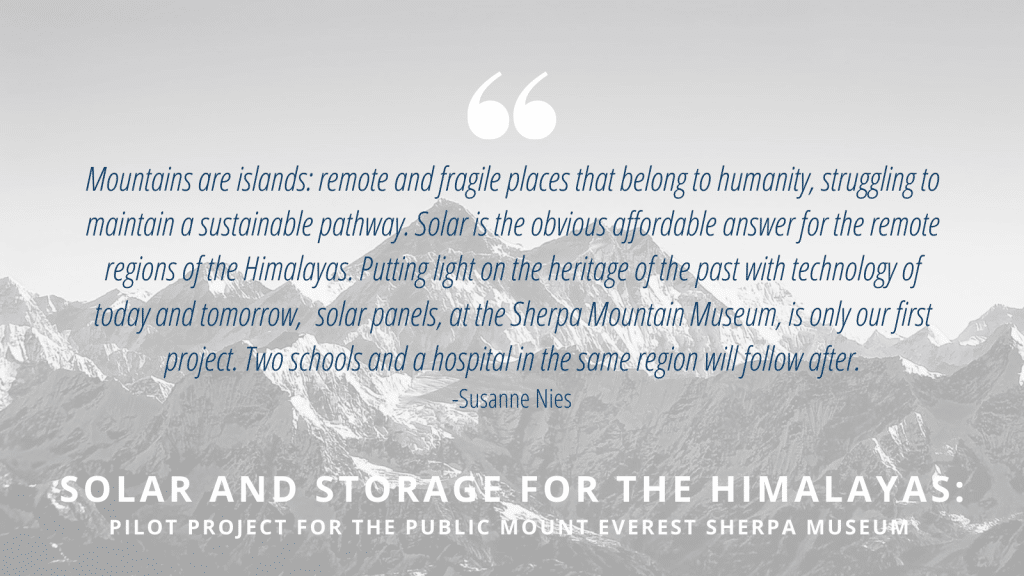

Call for Support: Solar and Storage for the Namche Bazar Everest Sherpa Culture Museum

Solar PV technology is the no-regret and cost-effective solution for off-grid areas and remote and isolated places like islands or mountains – perfectly suited for the Himalayas. It is for this reason that the Solar and Storage for the Namche Bazar Everest Sherpa Culture Museum project wants to apply solar solutions to public buildings, public goods.

The project aims to take an engineering approach that will hopefully spill over to many other mountain regions, starting with the pilot project at the Namche Bazar Everest Sherpa Culture Museum. Currently being redesigned, the museum that should be equipped with solar panels and a solar battery in 2020. The project coordinators believe that a label ‘sustainable mountains’ should be developed in parallel, allowing the hosting country to develop tourism even further and to protect their ‘universal garden’.

Learn more about the project and show your support here.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights