Financing for energy transitions

This brief puts together some of the reflections arising from FSR Global’s Energy Innovation Week, which had the underlying aim of exploring “Regulatory learning to realize financing for energy transitions”.

Financing for energy transitions: Reflections on Energy Innovation Week

In this brief, Miguel Vasquez and Daniel Schmerler put together some of the reflections arising from FSR Global’s Energy Innovation Week, which had the underlying aim of exploring “Regulatory learning to realize financing for energy transitions”.

Missed Energy Innovation Week? Join our newsletter for updates on events like this one!

New ways of entering into contracts in the energy market

When gearing up for Energy Innovation Week, we knew that our first step had to bring together the policy discussion on digitalization and the technical discussion on the Internet of Things (IoT). To that end, we organized the discussion in Session 1: Digitalization and long-term investment in energy assets, around smart transactions (contracts). The idea was to use the connection between distributed ledgers (say blockchain) and smart contracts. This is useful because, as we know from Institutional Economics, we can think of a broad economic perspective and talk about transactions instead of just contracts. In that context, the first question we were trying to deal with was: Are smart contracts substituting all traditional contracts? This question has two parts, and both are important for our reasoning: Is that substitution possible? Is that substitution efficient?

Our aim was to recast the previous question as: do we want all trade decentralized? The characteristic we discussed is that, in energy markets, when dealing with assets that require significant amounts of capital, we do not have contracts that specify a response for every contingency that may happen in the future. This difficulty in developing complete contracts account for a large portion of the corresponding transaction costs. And one very efficient way of dealing with these costs is centralization. So one may wonder: Will Distributed Ledger Technology – DLT change the nature of transaction costs? For some large investments, the fact that we encode contractual responses will not make the associated contingencies easier to foresee. Differently put, encoding will not change one of the elementary purposes of a contract: to deal with conflict (renegotiation).

Let us put forward an example for the sake of explanation: financial derivatives. Simply put, derivatives are instruments with an income stream that depends on a “contingency”. Very often, this contingency is a price (as in futures, options, etc). Sometimes, contingencies are events. Defining prices are not always easy (thus the pervasive use of auctions in energy markets), but from an automated contract standpoint, perhaps defining events is even more difficult. That is, from the smart contract perspective, there is an inherent difficulty associated with trying to encode a causal link between an event and the economic fundamentals of that event.

For instance, the case of the reliability adders in the original GB pool, which motivated the reform of the GB market. The pool was based on very complex payments rules (associated with income streams when bids were cleared). They included additional payments triggered when plants were available for dispatch. As the calculations were done day-ahead, plants declared themselves unavailable day-ahead and then re-declared available within a day to trigger the now higher payment. In this case, the governance structure of the GB market (in this case the regulator, not automated) intervened to reduce the incentives to pursue that strategy. Again, the automatization of this “trigger” was not deemed the most efficient way of organization. Actually, the GB reform in the 2000s travelled down an almost opposite path.

A smart contract is a contract that is easily agreed between the parts, but they do not help in facilitating a “continued bilateral relationship”. When conflict is difficult to solve, decentralization tends to be more expensive (as in infrastructure projects, as PPAs). When conflict is less relevant (logistics within a firm, a small neighbourhood) decentralization can be less expensive.

Differently put, even if the trading is centralized through a platform, complex contingent claims, that by definition cannot be automated, may represent better risk allocation mechanisms. And of course, the definition of the governance structure is highly relevant. Consequently:

- A smart contract is a contract that is easily signed (agreed between the parts) – Easier to deal with “site and time specificity”

- They do not help in facilitating a “continued bilateral relationship” (required for dedicated assets)

- Transaction costs theory proposes to use the ability to deal with specificity as a driver

- When conflict is difficult to solve, decentralization tends to be more expensive (as in infrastructure projects, as PPAs)

- When conflict is less relevant (logistics within a firm, a small neighbourhood) decentralization can be less expensive

A consideration here about digital contracts is that not everything is solved with the simple application of technology; thus, if a contract is imperfect of deficient, it will not be fixed by the simple fact that the blockchain or another tool is used in the contractual process. The most important thing is to design the contract well, think carefully about the type of project you want to execute and translate it into the clauses of the contract, and, in addition, test its functionality through mechanisms such as sandboxes.

So far, we identified that the role of digital contractual solutions involves coordinating not only signals on revenue streams but on the whole business model. In turn, this means that we need to look at the project/business not only from an operational viewpoint, but we need to include also the financial side of the challenge.

The finance of energy infrastructure

In that context, our next step is to look at potential roles for public participation in supporting the financing of energy infrastructure. The aim was framing the “digital” market design discussion of the first day under the header “business development”.

That is, in Session 2: Public financing of green innovation: Matching offers and demand for financing, we discussed what the needs to develop an energy project are. One of the main goals was to define what the main needs in terms of project financing are. We built on the idea that energy projects are often long-lived assets, with relatively very stable revenue streams, but with significant needs for upfront capital. This makes energy projects a very specific class of investment, where most of the risks are faced in the period where the investment enjoys no returns.

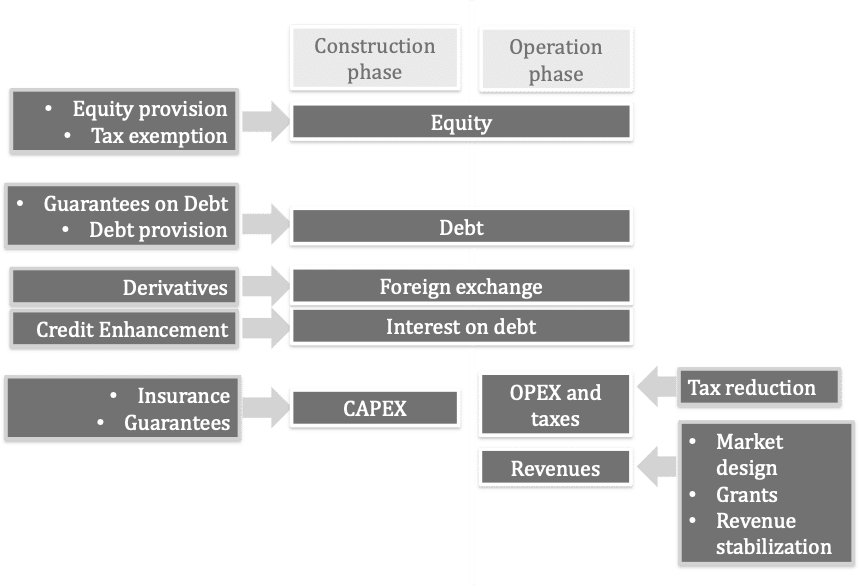

A schematic representation of alternatives for the participation of public financing is presented in the figure below, where we represent an energy infrastructure project as made up of two separate phases: the construction phase and the operation phase.

Much of what was discussed in the first day related to value creation through digital contracts is related to measures associated with market design or revenue stabilization (right-hand side of the figure). This figure, on the other hand, shows that when the energy project is large, the potential role of public measures might not be strongly related to the digital dimension (decentralization) of the coordination mechanisms.

Putting together the two previous points of view, we may separate energy projects related to new technologies under two broad headers: i) projects that require significant effort in upfront capital and ii) projects relatively small, with fewer capital constraints.

In order to understand to needs associated with new technologies, we may map the ecosystem of financing offer. In particular, we may identify:

Equity investors

- Corporates: Corporate may have different profiles (as the role of equity varies) depending on whether they participate in adding the project to their balance sheet or through project finance. Traditionally, utilities have been the main corporates with interest in infrastructure. However, in recent years, with the importance of green infrastructure increasing in various social and political agendas, other investors have become interested in infrastructure investment. A significant move observed in the infrastructure industry is interest from oil and gas companies in green infrastructure, such as wind offshore, storage, and perhaps carbon capture and storage (CCS).

- Institutional investors: Dedicated funds are growing in importance, but are still not a very relevant part of the investment. Sovereign funds, infrastructure funds, insurance and pension funds, exchange-traded funds, and so on may be a financing source under certain conditions. Nonetheless, these funds are not typically interested in exposures to relatively high risks.

Debt investors

- Commercial banks: Lending from commercial banks has specific constraints. Additionally, it is important to consider that Basel III, while addressing solvency problems in the markets, increased the costs of lending considerably.

- Institutional investors: Institutional investors in this context are similar to those discussed under equity investments. Particularly, insurance and pension funds increase their interest in infrastructure investment as this kind of asset matches their portfolio well.

- Governments and development banks: These institutions have been important sources of finance for infrastructure projects. Moreover, their role has consisted of providing various important functions to improve financial conditions for infrastructure investment, for instance, de-risking of projects, being an early mover in risky undertakings, and so on.

Green Energy Investments

This brings us to session three of Energy Innovation Week: Mobilising private investment for green, climate-resilient energy assets: The role of innovation in finance.

From this point of view, green energy investment may be divided into two separate groups: energy investments that can be identified as “green infrastructure” (large energy projects), and energy investments with relatively low needs for capital, which would require less standardization. As for the former group, the creation of a green infrastructure asset class would face, on the one hand, some of the financial barriers of traditional infrastructure projects. Hence, one faces the same difficulty as in other infrastructure projects to create an infrastructure assets class. From that point of view, the analysis made above of instruments to support the viability of these projects still applies.

Nonetheless, several aspects are specific to green projects:

- It is very difficult to compare green projects (being unlisted investments makes data gathering very difficult). In that sense, improving project data disclosure would be helpful for financial institutions. Moreover, regulated requirements on disclosure (transparency) may accelerate the creation of international benchmarks.

- We need to clear the meaning of “low carbon infrastructure”. To that end, a standard taxonomy of green investment needs to be created (as globally as possible). Correspondingly, this taxonomy requires the institutional architecture to define it.

- Energy systems tend to be locked into fossil fuel technology. Part of the explanation for this is the price of risk, but it is important to check periodically whether regulatory barriers still exist for the entry of new, cleaner and planet-friendly technologies.

About Energy Innovation Week: Financing for energy transitions

The electricity industry is the arena where various kinds of policies interact. The interplay between environmental and energy policies have been extensively studied and discussed. However, the innovation wave of the last years adds a new layer of policies to shape the evolution of the electricity industry: innovation policies. Transitions imply disruptive innovations but they should be also guided by policies that facilitate structural change and smooth out the process. In that context, although the combination of regulation and innovation is often challenging, they are nowadays closer than at any time before in the electricity industry.

In this context, the assumption that regulations can be crafted slowly and purposely, and then stay in place for long horizons without change, is being challenged by considerable innovation activity. This includes, importantly, deep changes in the possible ways to finance energy projects, and the emergence of a new ecosystem of offer and demand for financing. Consequently, regulatory practice faces the challenge of reviewing regulations (or creating new ones), enforcing them, and communicating with the public, at a significantly increased pace. And all that needs to be done simultaneously to dealing with legacy market designs.

The three Energy Innovation Week sessions intend to contribute the identification of common elements of the population of challenges that conform the current regulatory landscape, in order to define a framework that facilitates regulatory learning to realize financing of energy transitions: Digitalization and long-term investment in energy assets; Public financing of green innovation: Matching offers and demand for financing and; Mobilising private investment for green, climate-resilient energy assets: The role of innovation in finance.

Missed Energy Innovation Week? Join our newsletter for updates on events like this one!

Gratitude

First of all, we want to thank Florence School of Regulation for the opportunity they gave us to develop the Energy Innovation Week last October 2020. Also, we want to express our appreciation to the specific people who contributed with us to the development of this activity: Jean-Michel Glachant, Swetha RaviKumar Bhagwat, Pradyumna Bhagwat, Jessica Dabrowski and Gianluca Dolfi.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights