Decarbonising manufacturing firms in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System

This is the fourth and conclusive installment of the Topic of the Month: Reflections on Draghi's report

Decarbonising European manufacturing firms is critical to ensuring the EU achieves its climate neutrality objective set in the EU Climate Law of 2021[i]. In 2022, emissions from the manufacturing sectors – which include iron & steel, mineral oil, cement & lime, chemicals, pulp & paper, glass, and non-ferrous metals – accounted for 21% of total EU emissions. Activities in this sector contributed to the highest levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Europe, alongside the supply of electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning, with both sectors reporting 745 million tonnes of CO2-eq.[ii]

Industrial emissions have decreased, but progress remains insufficient, and there is a need to increase the reduction rate to be consistent with the trajectories towards the overall 2030 and 2050 objectives.

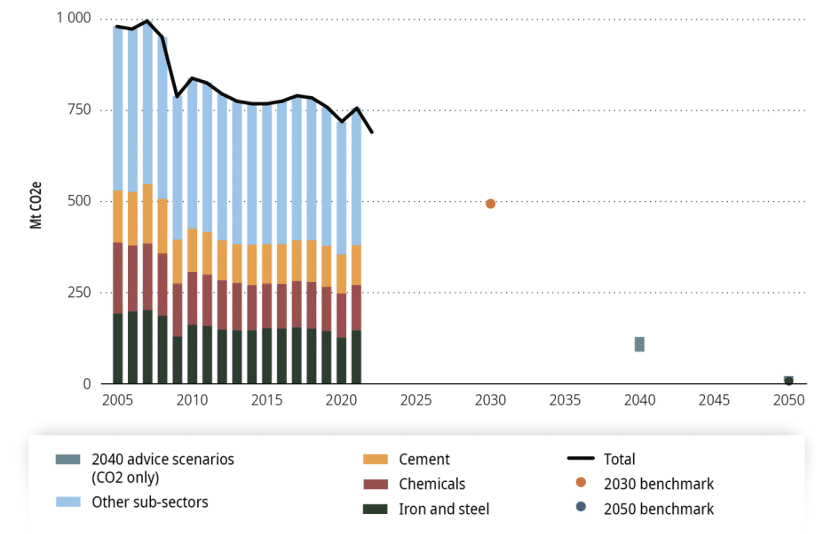

In their 2024 Assessment Report, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change highlighted “average annual reduction in 2005–2022 (– 17 Mt CO2e per year) needs to accelerate to – 24 Mt CO2e per year in 2023–2030 and – 19 Mt CO2e per year in 2031–2050 to be consistent with the trajectories towards the overall 2030 and 2050 reduction objectives” (Figure 1).[iii]

Figure 1: Overall progress in reducing industrial GHG emissions (source European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change)

Decarbonisation, however, must not come at the cost of economic competitiveness. The manufacturing sector is a key contributor to Europe’s economy for employment and output; policies that may negatively impact activity must be carefully designed, always considering the social repercussions. One challenge with decarbonisation is that the higher relative costs of decarbonised production can lead to output reduction and a higher reliance on imports. The Draghi report on European competitiveness warns: “Deindustrialisation in the EU in some of these sectors has already started, and may accelerate without dedicated policies.”[iv]

In 2023, the European Investment Bank (EIB) collected information on investment activities, financing requirements, and difficulties faced by manufacturing firms in the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) related to their decarbonisation activities.[v] The survey confirmed firms consider the EU ETS as a driver for innovation, whilst carbon cost uncertainty a hurdle. The survey also revealed that some firms were lagging behind their peers regarding their decarbonisation process.

Based on the key findings of the EIB survey and considering the economic importance of manufacturing firms in Europe, this article will discuss:

- Emission reductions of manufacturing firms in the EU ETS – decarbonisation or output reduction?

- The EU ETS as a driver for industrial innovation? Investment disparities reflect sectoral specificities.

- Laggards, by choice or despite efforts? A call to address industrial firms lagging behind in decarbonisation.[vi]

1. Emission reductions of manufacturing firms in the EU ETS – decarbonisation or output reduction?

Emissions from the manufacturing sectors are covered by the EU ETS, the pillar of Europe’s decarbonisation strategy: the coverage rate is above 75% of the total emissions for these sectors.[vii] Overall, emissions from manufacturing sectors in the EU ETS have decreased by 7.5% in 2023 compared to 2022. The European Commission reports this drop to be due to a combination of reduced output and efficiency gains, without specifying the ratio between these two levels.[viii]

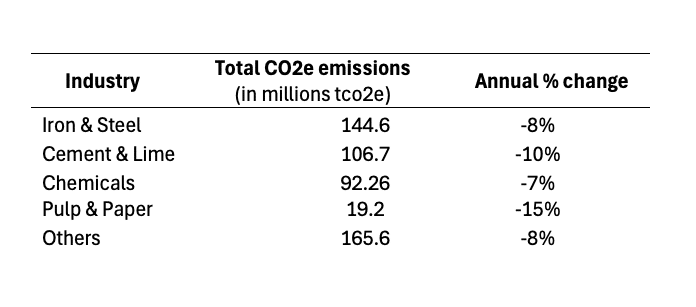

Table 1: 2023 emissions reported in the EU ETS for selected industries (source: Sandbag, author’s calculations)

Note: a reduction in emissions is recorded across all sub-sectors. Iron & Steel is the heaviest emitting sector among the manufacturing sectors regulated in the EU ETS.

In aggregate, European industrial production fell by 1.2% in 2023 compared to 2022, with a recorded decrease in production in about two-thirds of all industries.[ix] As stressed in the Draghi Report, this can be attributed to the higher relative energy costs faced by firms in Europe compared to its international competitors.[x]

Although to a limited extent, emissions costs have also pressured European competitiveness. The increase in carbon prices in the last 5 years has indeed led to an increased production cost. This impact is limited as carbon costs represented a small share of total production costs: 2% for European steel producers in 2019, and around 10% for cement producers in 2021.[xi] To limit the negative repercussions of carbon cost increase and support European producers’ competitiveness, firms at risk of carbon leakage have been receiving free permits.[xii] In aggregate, firms in the industrial sectors received a net surplus of permits compared to their total reported emissions in 2023.[xiii] With the recent Fit for 55 reforms to increase ambition, including the tightening of the cap and the gradual phase-out of free permit allocation, regulated firms are expected to feel more pressure from the EU ETS.[xiv] In this context, future EU carbon prices are expected to reach up to 250 €/tCO2 by 2030, and future carbon costs are thus expected to play a higher share of total production costs.[xv]

Considering the evolution of both emissions and output levels together is key to analysing the extent to which these industries are on their path to decarbonisation. The aim is to decrease emissions intensity, indicating a decoupling between the emissions and output levels. Since 2005, estimates suggest that the EU’s GHG intensity of steel, cement and chemicals has been relatively stable or even slightly increasing.[xvi]However, an accelerated reduction in industrial emission intensities has been noted since 2020, with considerable heterogeneity in the rate of decline across sectors. In 2023, the aluminium sector has seen the most significant decline in emissions intensity, whilst the steel and chemical sectors have increased theirs.[xvii]

2. The EU ETS as a driver for industrial innovation? Investment disparities reflect sectoral specificities.

The EU ETS is intended to incentivise firms to invest in and adopt low-carbon or carbon-neutral technologies to reduce their emissions intensity. Industrial firms in the EU ETS surveyed by the EIB perceive carbon pricing or taxation as important drivers for investment in green technologies and processes. However, the investment gaps that remain to decarbonise heavy emitters and the lack of adoption show the current policy framework has not been effective enough to spur the needed changes for the uptake of clean production.[xviii]

Furthermore, there appear to be significant differences between companies in terms of their willingness or ability to invest: the EIB survey finds that the percentage of total 2022 investment budget dedicated to decarbonisation varies from 30% to 50% across the surveyed sample. This result reflects the disparity in decarbonisation pathways of the different EU industries. For example, whilst the main emissions reduction pathway in the Iron & Steel sector is transitioning to electric arc furnaces, the most promising avenue for the Cement sector is the usage of carbon capture and storage (CCS) to capture the unavoidable process emissions.[xix] Both of these firm-level technological changes also depend on systemic changes such as increased green electricity supply and large-scale deployment of infrastructure. At the firm level, when the commercial viability of the most promising technology is not guaranteed, investments are made to decrease emissions at the margin. In the case of the cement industry, for example, as CCS is still not deployed at scale, decarbonisation has implied changing the cement formulations with lower quantities of clinker.

To incentivise the decarbonisation of EU manufacturing sectors, it appears important to take a sector-specific or a value chain approach rather than a technology-focused approach. The risk of having the latter is to structurally create an over-reliance on a certain technology and overlooking alternative options that would result in deeper and faster decarbonisation.[xx] The design of the free permits distributed to industrials in the EU ETS should be reassessed in this direction to ensure it effectively rewards decarbonisation. Taking the example of the Cement sector, the benchmark used for free permit allocation is defined based on clinker production. In that way, the design favours the established production method: currently, a producer is not incentivised to change its cement production process by reducing clinker for a less emitting alternative as it would decrease the volume of free permits it receives. Switching to a product benchmark instead would correct this perverse effect and push decarbonisation in a technology-neutral manner.[xxi]

3. Laggards, by choice or despite efforts? A call to address industrial firms lagging behind in decarbonisation.

As the credibility and the stringency of the EU ETS increased over the years, it is expected that all regulated firms would undertake decarbonisation measures to a certain extent. Interestingly, some 18% of the surveyed manufacturing firms reported not yet having a decarbonisation strategy in place in 2023. It can be interpreted that these firms project their business to continue as usual. Further, some firms have substantially increased their emissions intensity relative to their peers in the sectors.[xxii] These firms represent “vulnerability pockets” as they will be the most negatively impacted by the forthcoming increase in climate stringency.

One interpretation of the phenomenon of the “business-as-usual firms” or the firms in the “vulnerability pockets” is that some incumbent actors do not consider decarbonisation as a strategic priority for their activity. Along this narrative, these firms are confident that their Member States (MS) will protect them from the negative effects of stricter environmental policies. As these firms often provide employment and growth opportunities on a regional or national scale, MS have an interest in shielding them at the expense of the EU’s fair competition or decarbonisation objectives. The previous overallocation of free permits exemplifies this phenomenon in action. Another interpretation is that these firms lack the means to tackle their decarbonisation. Small and medium enterprises in the energy-intensive sectors have been found to lag behind larger firms in terms of environmental action, hindered by a lack of information and awareness, regulatory hurdles, innovation assets, skills gaps and financing constraints.[xxiii] These two interpretations are not mutually exclusive: these two types of firms likely co-exist.

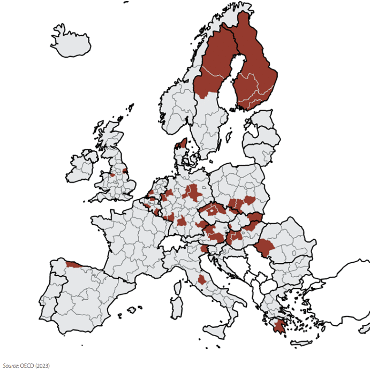

Figure 2: Regions most exposed to the transition to climate neutrality in key manufacturing sectors (source OECD)

Faced with the challenge of decarbonisation, some activities are poised to decline (or even terminate) in specific locations. Indeed, shifting to new production pathways will bring new cost structures and can change the optimal locations for an industrial site. This structural change will not be uniform across Europe: regions in Central and Eastern Europe are the most exposed (Figure 2). As these regions are often relatively socioeconomically weak, it raises distributional concerns.[xxiv] There is a need to accompany this structural change. A unified European approach seems appropriate to develop a strategy for the new landscape of clean EU industry. As mentioned in the Draghi report, this would provide a business case for a joint “decarbonisation and competitiveness” of the EU industry.[xxv] Such an approach could build on existing policy flagships such as the EU’s Just Transition Mechanism and Net Zero Industry Act to deploy impactful measures like reskilling programmes or conditioning industrial aid to decarbonisation targets. The upcoming Clean Industrial Deal will be a key opportunity to introduce and develop these measures.

[i] Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (“European Climate Law”).

[ii] Estimation from Eurostat data (env_ac_ainah_r2).

[iii] Report ‘Towards EU climate neutrality: progress, policy gaps and opportunities’, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change

[iv] Mario Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, September 2024. (p. 92)

[v] This information was collected by the EIB for the 2023 extension of the annual EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS). The questions were designed in collaboration with the EUI, as part of the LIFE COASE project. A complete overview of the main results can be found in the EIB Investment Report: Transforming for competitiveness (Box A Manufacturing firms in the EU Emissions Trading System – what makes the leaders stand out from the rest? P.209 – P 214).

[vi] The content of this article will be published as a policy brief which will also include a discussion on the role of uncertainty for investments in low-carbon technologies. Raude, M., Heinrich, L., Ferrari, A & Borghesi, S. (Forthcoming). Decarbonising manufacturing firms in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System. The authors are grateful to Aliénor Cameron and James Kneebone for their helpful discussions and comments on the policy brief.

[vii] Raude, M., Mazzarano, M., & Borghesi, S. (2024). EU Emissions Trading System sectoral environmental and economic indicators. European University Institute.

[viii] Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the functioning of the European carbon market in 2023

[ix] According to the Eurostat production of industry index (sts_inpr_a).

[x] Mario Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, September 2024.

[xi] Estimations from Medarac et al 2020 for steel, and Cembureau for cement.

[xii] The volume of free permits distributed to industrial sites depends on defined sectoral benchmarks. Carbon leakage refers to when a firm relocates its production to a jurisdiction with less stringent climate policies.

[xiii] Author’s estimation from EUTL data.

[xiv] Cameron & Garrone (2024) already identify that after 2018, changes in emissions intensity led to opposite changes in corporate performance, showing the importance of the increased regulatory stringency of the system.

[xv] Raude, M., Heinrich, L., Ferrari, A., Ekins, P., Osorio, S., & Borghesi, S. (2024). Climate neutrality: policy scenarios for emissions trading. European University Institute.

[xvi] Emissions intensity is commonly measured by taking the ratio between GHG emissions and gross value added or GHG emissions and tonne of product. For more refer to the report ‘Towards EU climate neutrality: progress, policy gaps and opportunities’, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change

[xvii] 2024 State of the EU ETS report, or for more recent data, refer to Raude, M., Heinrich, L., Ferrari, A & Borghesi, S. (Forthcoming). Decarbonising manufacturing firms in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System.

[xviii] See Figure 77 on climate-related investments (p.243) from the report ‘Towards EU climate neutrality: progress, policy gaps and opportunities’, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change

[xix] Refer to JRC and Marmier, A (2023) for cement, Garcia Higuera and Van Woensel (2021) for steel.

[xx] CCU/S availability for steel (Sandbag, 2024)

[xxi] This is a short-term measure as free permits are foreseen to be phased out and replaced by the CBAM.

[xxii] EIB Investment Report: Transforming for competitiveness (p 217)

[xxiii] SMEs account for more than 30% of the GHG emissions in the EU manufacturing sectors. For more information refer to OECD (2021), “No net zero without SMEs: Exploring the key issues for greening SMEs and green entrepreneurship”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 30, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[xxiv] OECD (2023), Regional Industrial Transitions to Climate Neutrality, OECD Regional Development Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[xxv] Mario Draghi, The future of European competitiveness, September 2024.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights