Carbon pricing proves to be resilient but needs acceleration

Insights from the World Bank’s State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023 report

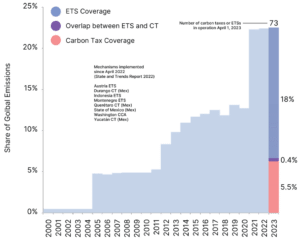

Although explicit carbon pricing has been a mitigation tool for a long time, it has only really gained momentum in the past decade. As outlined in the World Bank’s State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023 report, around a quarter of global Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions are currently covered by a carbon price, compared to just 7% about 10 years ago. In fact, carbon pricing policies have shown remarkable resilience this past year in the face of an energy crisis, economic uncertainty, and geopolitical instability. Despite significant economic pressures, governments have prioritized emissions trading schemes and carbon taxes by either retaining or expanding carbon pricing policies. This is in contrast to previous downturns, where carbon pricing policies were relaxed, repealed or reduced. In fact, there were only a few instances in the last year where governments relaxed carbon pricing in response to the energy crisis by delaying the start of a new instrument (e.g., Austria), postponing a planned expansion or price increase (e.g., Germany), or in repealing a carbon tax (Slovenia). As such, there are 73 national and sub-national jurisdictions which have a carbon pricing instrument in place or are planned in 2023 (Figure 1). However, most of the carbon pricing instruments currently in operation are in high-income countries.

Figure 1: Global GHG Emissions Covered by ETSs and Carbon Taxes

Overall, greater ambition needs to be reflected across all mitigation policies to achieve the Paris Agreement goals. For carbon pricing as a mitigation instrument, this needs to be reflected in both the price and coverage in countries already implementing carbon pricing. In addition, it requires greater uptake of carbon pricing in emerging economies. We have seen promising signs, with several governments in emerging economies introducing or exploring the potential for carbon pricing. The World Bank’s Partnership for Market Implementation (PMI) is supporting 17 developing countries in this endeavour. A good illustration of this encouraging development is Indonesia, which recently launched its ETS for coal fired power stations, and, with PMI support, is targeting to promote other carbon pricing instruments. A range of other governments have indicated that they are actively considering carbon pricing, including Brazil, India and Vietnam, as well as many Western Balkan countries looking for EU accession.

Unsurprisingly, the drivers for implementing carbon pricing vary, and include aspects beyond least cost abatement. We’ve seen the announcement (and subsequent adoption) of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism to be a powerful motivator for consideration of carbon pricing, even if the likely implications are not completely clear yet. Several jurisdictions, such as Ukraine, Uruguay, and Taiwan, China have already cited the CBAM proposal as a driver for pricing emissions.

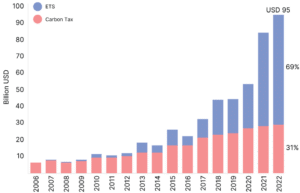

Another important driver, especially in emerging economies, is the potential to generate revenue from carbon pricing. A good example is in Mexico, where five subnational governments have introduced a carbon tax. Many of these, including the State of Mexico, have been aimed at increasing local tax revenue and broader fiscal reforms. The potential for carbon pricing as a fiscal tool is demonstrated by the significant increase in global revenue from ETSs and carbon taxes, which touched almost USD 100 billion in 2022 – a five-fold increase over a decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Global revenues from carbon taxes and ETSs (NOMINAL)

In all these cases, government priorities and national circumstances underpin the driver behind carbon pricing. Accordingly, there can be no “one size fits all” and the design and implementation of carbon pricing needs to reflect local conditions.

While we’ve seen significant progress in the past years, carbon pricing, and mitigation policy more generally, still has a long way to go. While price levels are not a reflection of mitigation ambition, they do provide an indication of how carbon prices are tracking. Generally, prices remain below the levels recommended by the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices (USD 50 to USD 100 per metric ton CO2e by 2030). In fact, less than 5% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are covered by a carbon price at or above the inflation-adjusted range recommended by 2030. In this context, and noting Canada’s call to increase the proportion of global emissions covered by a carbon price to 60% by 2030, significant action is required to increase ambition in terms of both price and coverage. It is hoped that the intensification of global efforts, including updated nationally determined contributions with increased ambition and the operationalization of Article 6, can help sustain and accelerate the momentum building around carbon pricing over the past decade.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights