Carbon markets or climate targets? We need both

Reflections on the evolution of the EU climate tools

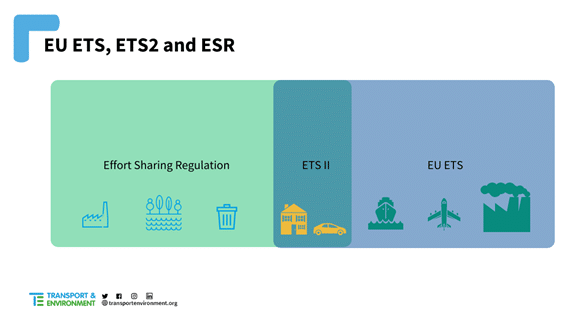

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is not only the world’s biggest carbon market in value but also successful. In 2022, emissions falling under its scope went down by 37.5% compared to 2005 levels, while its average price reached around 80 EURO. Within its latest reform, the market’s scope was extended to more sectors (CO2 emissions from maritime transport, road transport and buildings via a new separate ETS, the so-called ETS2) and its cap decreased to achieve -62% of emissions in 2030 compared to 2005.

The European Commission, academics, and stakeholders are already studying how the ETS will develop after 2030. By the end of this decade 2020-2030, the Commission will evaluate whether to merge the two EU carbon markets, the ETS and ETS2. In addition, considering that agriculture is not sufficiently decreasing its emissions and that the Common Agriculture Policy has not been effective so far in limiting the climate and environmental impact of agricultural practices, the EU is exploring options to extend the polluter-pays-principle to the sector.

What is on the horizon is the progressive extension of the ETS to the whole of the economy in order to set the right incentives for decarbonisation. Such evolution makes us question what would be the future of another pillar of EU climate policy, the Effort Sharing Regulation (or ESR).

The ESR covers the emissions of land transport, buildings, waste, agriculture and small industry (~60% of EU emissions) where a collective EU target of 40% reduction by 2030 relative to 2005 levels is set. This collective goal is shared by all EU countries, with individual national climate targets ranging from -10% to -50%. Practically, the ESR regulates emissions of those sectors falling out of the EU ETS scope by means of national targets, whereby emissions cuts are the result of EU and national sectoral regulations[1]. With an economy-wide carbon price, some wonder whether national climate targets are still needed.

Climate targets and carbon markets are not, however, mutually exclusive. While targets set the direction of mitigation action, carbon markets are one of the tools to get there. This is valid both at the EU and the national level. Multiple examples of coexistence of climate targets with carbon markets are found in national climate legislation. For instance, Germany, Finland, and Denmark[1] set economy-wide emissions reduction targets for 2040 and 2050, while the cap set by the ETS remains applied in those countries. Moreover, within the ESR system, countries such as Germany and Portugal adopted national carbon prices in the sectors of road transport and building (by means of a tax or a carbon market) to reach their national ESR targets.

National targets ensure that national responsibility is taken behind an EU’s collective goal. Hence, if the carbon price of the EU ETS was extended to the whole economy, an option could be to also include all sectors of the economy under the scope of national climate targets. It could be done via a reform of the ESR, or amendments to the Governance Regulation or even the European Climate Law.

It would not be the first time in EU legislative history that a collective economy-wide climate goal is shared among member states in the form of national targets. When the European Community joined the Kyoto Protocol, committing to cut emissions of 6 GHGs by 8% between 2008-2012 (v. 1990 levels), the Burden Sharing Agreement among member states redistributed that target into individual contributions.[2] The ETS was in fact adopted in 2005 as a tool to comply with the Kyoto Protocol. While the ETS covered industrial emissions, additional regulations and standards would be adopted by the Community and the member states to tackle other sectors’ emissions,[3] but national targets still covered the whole economy.

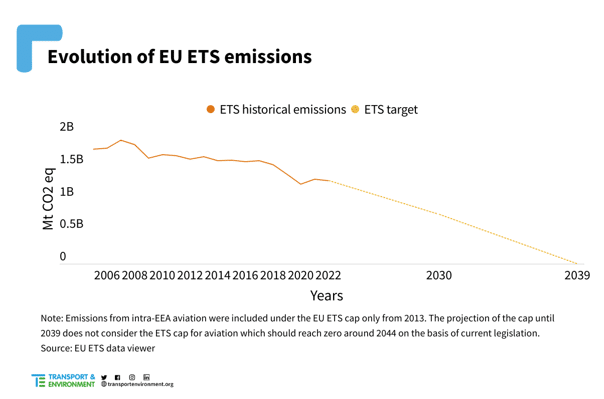

Such a design for the EU climate policies would have another implication: if the ETS carbon price risks reaching politically unacceptable levels, governments could adopt additional sectoral regulation to mitigate that price. If the ETS cap approaches levels close to zero (this may happen towards 2040 or 2044 if the current cap or regulation is maintained) and the cost of abating technology falls, technologies mature, and heterogeneity of technological solutions decreases, the advantage of carbon markets versus standards would diminish,[4] making sectoral regulation a more efficient option.

Hence, the alternative between the EU ETS and national climate targets is a false dilemma and policy-makers’ task will be that of transforming both to make them fit for climate neutrality.

Author’s bio

Since 2021 Chiara Corradi is Climate Policy Officer at Transport&Environment, the European federation of NGOs campaigning for sustainable transport. Based in Brussels, her area of work encompasses EU climate policies such as the Effort Sharing Regulation and ETS for road transport and

buildings.

After the Bachelor in political science at the University La Sapienza in Rome, Chiara obtained her Master’s in International Relations and European Studies at the University of Florence in 2019 and further specialised with a 1-year Master’s in international politics at the LUMSA University in 2020-2021.

[1] Ecologic Institute (2023) Climate Framework Laws Info-Matrix. Ecologic Institute, Berlin. https://www.ecologic.eu/19320

[2] Marjan Peeters, Natassa Athanasiadou (2020) The continued effort sharing approach in EU climate law: Binding targets, challenging enforcement? Review of European, Comparative and International Environmental law. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/reel.12356;

[3] Per-Olov Marklunda and Eva Samakovlis (2007) What is Driving the EU Burden-Sharing Agreement: Efficiency or Equity? Journal of Environmental Management. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479706003094

[4] Pahle M. (2023) The Emerging Endgame: The EU ETS on the Road Towards Climate Neutrality. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4373443 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4373443

[1] Notice that even with the introduction of the ETS2, road transport and buildings remain under the ESR scope.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights