Can trees and poles live side by side?

by S. Ambec and C. Crampes

Toulouse School of Economics

Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) filed for bankruptcy on January 29, 2019. The Californian energy supplier, which was valued at more than $25 billion at the beginning of November 2018, was, mere months later, only worth $4 billion following suspicions of responsibility in the fires that ravaged northern California, killing 86 people and destroying 15,000 homes.

Compensation and bankruptcy for reorganization

California energy suppliers are regularly condemned for their responsibility in starting forest fires. In 2007, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric had to pay $37 million and $14.4 million respectively. In 2015, PG&E paid $8.3m in compensation. The November 2018 fires may have been caused by sparks from a high voltage line owned by PG&E. If the investigations currently being conducted conclude that it is liable, PG&E will have to pay an estimated $30 billion in compensation. This exorbitant risk explains why the company has placed itself under Chapter 11, a provision of U.S. law that allows it to continue to operate until a federal judge has ruled on a plan to reorganize its business affairs, debts, and assets. PG&E’s 24,000 employees should therefore keep their jobs and its 16 million customers should continue to be supplied, but their bills should rise to cover the cost of insurance and additional security investments, while waiting to see if compensation will also be required for victims. If this is the case, the company may be allowed to pass on the extra cost to its customers through an increase in energy prices, as happened in 2001 after the Enron crisis. PG&E remained under Chapter 11 from April 2001 to April 2004 and paid $10.2 billion to its creditors.

Obligation of result

Researchers in contract economics and insurance have done a lot of work on how to draft a contract when some decisions that one party will have to make are not directly verifiable by the other party. Since it is always inefficient to sign a contract by linking the price to unverifiable actions, commitments should only cover observable results, not the hidden means used to achieve those results. Thus, the fire prevention contract between power system operators (here PG&E) and the authorities (California Public Utilities Commission, CPUC) should provide for rewards and/or penalties depending on the power cuts measured, the number of fires and victims, and the extent of the damage, regardless of the cause. Such regulation creates a very strong incentive to spend a lot on safety, but without any guarantee that the result will be up to the task. This is an extreme application of the adage “the more I work, the luckier I am” with the double risk of the unlucky hardworking (despite the important preventive efforts made by the operator, the result is disastrous) and the lucky lazy (the result is good despite a low level of effort).

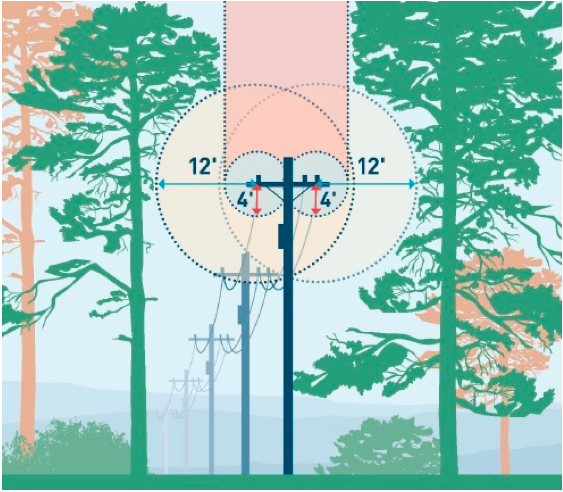

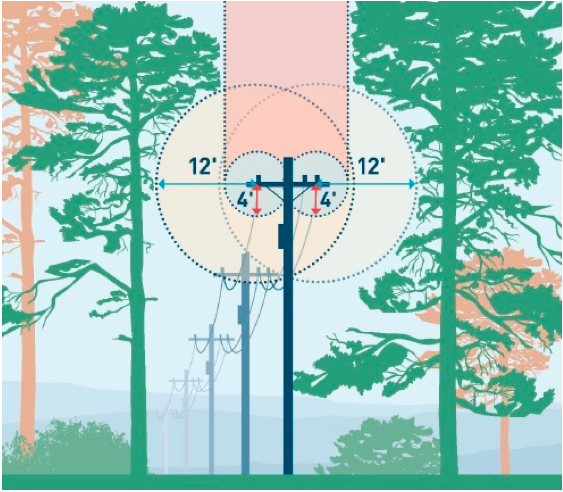

In practice, this problem, known as moral hazard, is resolved in a slightly less radical way by the regulatory bodies: the contract is drafted in such a way as to give the operator a presumption of liability, but when an accident or incident occurs, the authority conducts an investigation to seek possible proof of non-responsibility. In California, the stakes are high because, under the law, the company must pay for the consequences of the fire if its equipment triggered it, even if it appears that it has scrupulously complied with safety rules, such as the pruning obligations given in the illustration below.

source: PG&E’s wildfire mitigation plan 2018

It is therefore not enough that there is a forest fire for the owner of a power line crossing the forest to be finally found responsible, but it is very likely that he will be, unless the investigation leads to the identification of another “more likely” culprit. For example, PG&E, which was also involved in fires in October 2017 in northern California, was cleared in January 2019 after an investigation by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE).

A similar cut-off, but for much less dramatic facts, threatened the distributor EDF Energy Networks in July 2009. Ofgem, the UK energy regulator ruling on power outages in the Dartford area following a transformer fire (94,000 customers in the dark, many for more than 24 hours) considered imposing a £2 million fine on the company. The argument was that, although the fire was caused by vandalism, it could have been avoided if the operator had carried out multiple inspections on the site. Ofgem finally concluded that this was an exceptional event and that there was no evidence that the distributor’s “actions or lack of actions” were at the root of the incident. It has therefore not imposed on EDF Energy Networks the revenue penalties provided for in its incentive regulation contract.

The arsonist and the burnt

The most radical solution to prevent fires in heavily forested areas is the shift to underground distribution lines. But for cost reasons, burial can only be carried out very gradually, and in areas where there is no flooding or landslides. Less expensive in terms of infrastructure but very unpopular is the disconnection of lines during storms. If the branches torn off by the wind fall on unpowered lines there is no risk of fire. But of course, there must be an alternative for vulnerable customers whose line is interrupted, especially those on medical assistance. And, as Meredith Fowlie mentions in her blog post, preventive outages run counter to PG&E’s obligations to provide electricity to its customers. If we don’t want or can’t eliminate the risk of sparks, let’s make the flammable material disappear! PG&E, which claims to have cut 160,000 trees in 2018, plans to increase the figure to 375,000 in 2019. Brushing and pruning operations along the lines are expected to increase from 760 miles to 2,450 miles in the same years. It is also planned to increase the number of controls on pylons, lines, transformers and to develop the warning system.

Who is to be held responsible is a subject addressed by A.C. Pigou in “The Economics of Welfare” (1920) concerning crop fires caused along railway tracks by sparks from locomotive boilers. He advocated charging the railway company for the value of crops destroyed by fire. Forty years later, Ronald Coase in “The Problem of Social Cost” noted that this public policy is not necessarily efficient because it can be less costly to do without agricultural activities along the tracks than to slow the development of rail. Rather, Coase proposed to allocate rights to one or the other of the parties and let them negotiate the most efficient solution (train or no train, with or without agricultural activity), accompanied by adequate compensation.

Returning to the contract for fire prevention in forests crossed by power lines, commitments to burying and disconnecting are verifiable and can therefore be contracted. This is less true of other measures. For example, if a fire breaks out, vegetation disappears and it is impossible to verify whether brush and trees have been removed in the vicinity of the fault lines.

* * *

With global warming, the number of drought episodes will necessarily increase and so will forest fires. The coexistence on the surface between flammable vegetation and power lines likely to ignite it will become increasingly difficult. Since we (fortunately) don’t know how to grow trees underground, it is the power lines that will have to give way on the surface, but it is a very expensive solution. We could still decide to implement preventive power cuts. Though, before making it a routine prevention tool, it is necessary to prepare the populations concerned for the risk of disconnection, in particular by encouraging the installation of solar panels and batteries for temporary self-consumption.

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights