Looking beyond the decarbonization-competitiveness dilemma

LIFE COASE – Collaborative Observatory for ASsessment of the EU ETS

The EU’s heavy industry faces a dual imperative: decarbonize rapidly to meet climate targets while remaining competitive in global markets. This tension between climate ambition and industrial competitiveness often dominates policy debates. Yet is this always a trade-off?

This blog post explores the conditions under which cutting emissions can enhance competitiveness rather than undermine it, with a particular focus on technological and policy conditions.

How will industry reach net zero?

There is no single guaranteed pathway to a net-zero EU industry. However, most scenarios converge on five broad options for industrial decarbonization:[1]

- Electrification: replacing fossil fuel combustion with electricity.2

- Fuel switching: moving from fossil fuels to biomass or hydrogen.

- Carbon capture and storage (CCS).

- Alternative production routes: hydrogen-based or electrified processes.[2]

- Resource and energy efficiency (REE).

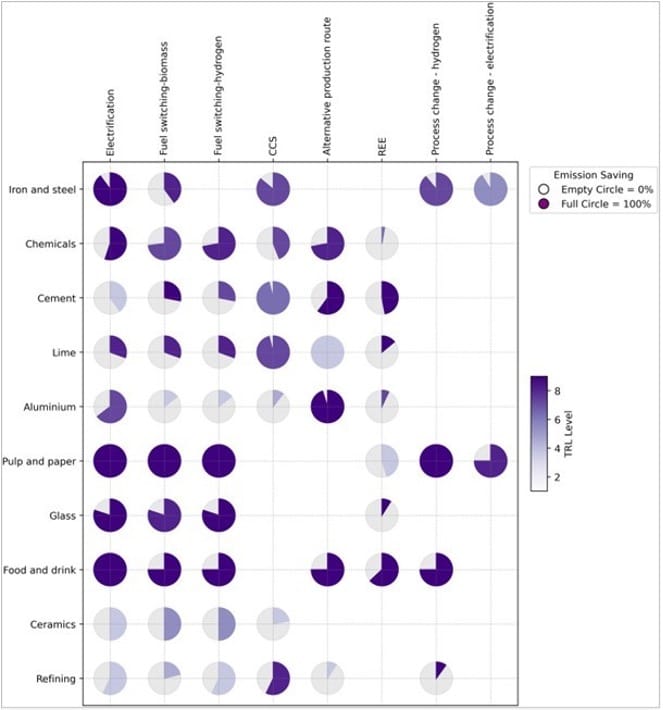

Source: Gailani et al. (2024)[3]

Note: TRL is measured on a scale going from 1 to 9, with each level representing a stage of a technology’s research and development process. The levels go from conceptualization (1) to normal commercial operation (9).

Figure 1 shows how each of these options varies in terms of its emissions reduction potential, and technological readiness level (TRL).[4] For example:

- Electrification offers large abatement potential for steel and glass but very little for cement.

- CCS is critical for cement and lime but less relevant for aluminum.

These differences matter because they shape how technology adoption affects firm competitiveness. A high abatement-potential but low-TRL technology like CCS in aluminum poses different challenges than a low abatement-potential but high-TRL options like energy and resource efficiency in lime production.

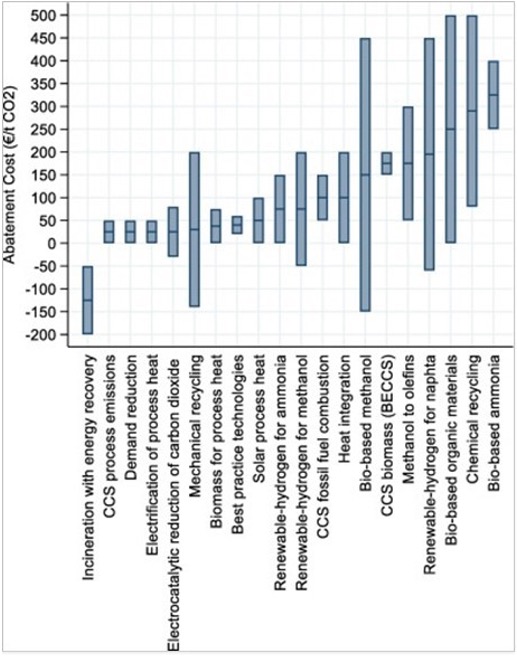

TRLs and emission reduction potential are only part of the equation for industrial decarbonization. Costs matter too – both upfront capital expenses (CAPEX) and ongoing operating expenses (OPEX). CAPEX reflects the investment needed to deploy a technology, while OPEX captures the marginal cost of avoiding one tonne of CO2 once the technology is in place. In the chemical sector for example, these costs can range from -€200 per tonne (a net gain) to €500 per tonne, depending on factors like infrastructure, energy, labor, and input prices (Figure 2).[5]

Beyond these direct costs, firms also face financing costs added on top of CAPEX, which depend on technology risk as perceived by companies and their lenders and therefore vary with TRL (immature technologies generally entail greater risk). Additional transition-related costs can also arise, including stranded assets[6], the need to overcome capital inertia, and other adjustment costs.[7]

Source: Rekker et al. (2023)[8]

Together, cost and TRL are critical for understanding how a technology’s deployment will affect firm competitiveness. Table 1 illustrates examples of technologies categorized by TRL, capital expenses (CAPEX), and operating expenses (OPEX). OPEX include costs that are exogenous to company decisions, like the cost of electricity and other inputs.

Source: Authors based on Rekker et al. (2013)5, Wei et al. (2019)[9], Glenk et al. (2024)[10], IEA (2018), IEA (2023), Cooper et al. (2025)[11]

What drives competitiveness?

Competitiveness is no longer just about cost efficiency. It now encompasses resilience, adaptability, and strategic foresight.

The compete-connect-change framework captures this multidimensional view:[12]

- Compete: ability to deliver goods and services efficiently and reliably.

- Connect: ability to access and act on information through networks and digital tools.

- Change: strategic adaptability to shifting markets and technologies.

Policies that support these pillars through infrastructure, digital access, and innovation ecosystems are essential for firms navigating the transition to net zero.

Connecting the dots: decarbonization and competitiveness

How do decarbonization options interact with these drivers?

- Compete: Evidence suggests that firms cutting emissions tend to become more competitive.[13] However, most actions to date have involved low-CAPEX, low-OPEX measures like energy efficiency. Few large-scale investments have been made, and many are stalled by high or uncertain operating costs (such as from volatile input prices, including e.g. electricity) and an uncertain policy framework.[14] Larger changes will require policy support (such as long-term contracts).

- Connect: The “Connect” pillar of competitiveness relates to all decarbonization technologies, but especially those with high costs and low TRLs, as they require the most policy support. For these technologies, companies and authorities should work together to identify whether infrastructure, skills, and demand make them a viable option. Because immature and uncertain technologies respond differently to policy incentives, the type of support instrument also matters. Price-based tools (e.g., carbon prices, contracts for difference) and quantity-based tools (e.g., quotas) provide different investment signals, which underscores the need for coordination to tailor support to each technology’s maturity and risk profile.[15]

- Change: The EU needs to secure a first-mover advantage on technologies with low TRLs rather than adopting a “wait and see” approach. If companies are unable to carry out R&D activities to increase the TRL of a promising technology, the EU should provide financial support to companies or institutions that commit to doing so.

Why this matters for policy

The EU has set itself ambitious targets, but the question remains: how can it ensure that climate ambition does not hollow out Europe’s industrial base? The answer lies in smart and flexible policies that support both the diversity of decarbonization solutions and the multiple dimensions of competitiveness. Policies should aim at ensuring that investments in decarbonization are profitable for firms. Key actions to achieve this include:

- Giving clear long-term signals through a stable and increasing carbon price that reflects the EU’s climate policy ambitions.

- De-risking high-CAPEX and uncertain/high-OPEX investments through grants, guarantees, and long-term contracts (including carbon contracts for difference).

- Strengthening connectivity by investing in digital infrastructure, industrial knowledge-sharing platforms, and simplified support policies.

- Enabling adaptability via innovation funding, workforce retraining.

Without these measures, firms may delay action fearing competitive disadvantage. With them, decarbonization can become a source of resilience and growth.

- [1] Bashmakov, I.A., L.J. Nilsson, A. Acquaye, C. Bataille, J.M. Cullen, S. de la Rue du Can, M. Fischedick, Y. Geng, K. Tanaka, 2022: Industry. In IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. https://doi:10.1017/9781009157926.013

- [2] Electrification and alternative production routes are options for industrial decarbonization that are conditional on having low-carbon electricity.

- [3] Gailani, A., Cooper, S., Allen, S., Pimm, A., Taylor, P., & Gross, R. (2024). Assessing the potential of decarbonization options for industrial sectors. Joule, 8(3), 576–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2024.01.007

- [4] Technological readiness levels (TRL) measure a technology’s commercial maturity. A technology that only exists as an unproven concept has a very low TRL, while a technology that is fully operational and has been commercialized has a very high TRL.

- [5] Gailani, A., Cooper, S., Allen, S., Pimm, A., Taylor, P., & Gross, R. (2024). Assessing the potential of decarbonization options for industrial sectors. Joule, 8(3), 576–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2024.01.007

- [6] Pfeiffer, A., Hepburn, C., Vogt-Schilb, A., & Caldecott, B. (2018). Committed emissions from existing and planned power plants and asset stranding required to meet the Paris Agreement. Environmental Research Letters, 13(5), 054019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/AABC5F

- [7] Storrøsten, H.B. Emission Regulation of Markets with Sluggish Supply Structures. Environ Resource Econ 77, 1–33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00433-0

- [8] Rekker, L., Kesina, M., & Mulder, M. (2023). Carbon abatement in the European chemical industry: assessing the feasibility of abatement technologies by estimating firm-level marginal abatement costs. Energy Economics, 126, 106889. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENECO.2023.106889

- [9] Wei, M., McMillan, C. A., & de la Rue du Can, S. (2019). Electrification of Industry: Potential, Challenges and Outlook. Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports, 6(4), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40518-019-00136-1/TABLES/1

- [10] Glenk, G., Maier, R., & Reichelstein, S. (2024). Assessing the costs of industrial decarbonization. ZEW Discussion Papers, No. 24-061. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/312180

- [11] Cooper, C., Brooks, G., Rhamdhani, M. A., Pye, J., & Rahbari, A. (2025). Technoeconomic analysis of low-emission steelmaking using hydrogen thermal plasma. Journal of Cleaner Production, 495, 144896. https://doi.org/11.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2025.144896

- [12] Falciola, J., Jansen, M., & Rollo, V. (2020). Defining firm competitiveness: A multidimensional framework. World Development, 129, 104857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104857

- [13] See Dechezleprêtre & Sato (2017) for a literature review and Dechezleprêtre et al. (2023) and Cameron and Garrone (2024) for recent evidence.

- Cameron, A., & Garrone, M. (2024). Carbon Intensity and Corporate Performance: A Micro-Level Study of EU ETS Industrial Firms. https://doi.org/10.2873/188206. Conference Paper. Single Market Economics Conference Papers.

- Dechezleprêtre, A., & Sato, M. (2017). The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Competitiveness. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 11(2), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/REEP/REX013

- Dechezleprêtre, A., Nachtigall, D., & Venmans, F. (2023). The joint impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 118, 102758. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEEM.2022.102758

- [14] Gowrisankaran, G., Langer, A., & Zhang, W. (2025). Policy Uncertainty in the Market for Coal Electricity: The Case of Air Toxics Standards. Journal of Political Economy, 133(6), 1757–1795. https://doi.org/10.1086/734779

- [15] Krysiak, F. C. (2008). Prices vs. quantities: The effects on technology choice. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5–6), 1275–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPUBECO.2007.11.003

Don’t miss any update on this topic

Sign up for free and access the latest publications and insights