Network Industries Quarterly, Vol. 18, No 4 – Reform of the Railway Sector and its Achievements

In the last three decades, state-owned railways have been reformed in many countries.

The Japanese National Railways (JNR) was the first railway system to be divided and corporatized in 1987. In the following year, the Swedish State Railways (SJ) was reformed by introducing vertical separation, and this case had much influence on the stipulation of wider EU railway policies. Although the EU railway policies were stipulated based on regional context specificities, these policies and their results have been discussed even in some non-EU countries and have tended to have large impacts on the railway sector of those countries. Nevertheless, there are several other countries where the railways were reformed by different models and could improve the performance by certain measures such as inviting private investments, avoiding cross-subsidies among different divisions, liberalising the management of railways, and introducing intra-modal competition by an appropriate means.

The railway sector is required to compete with other modes of transport, especially roads to attain environmental regions. When it comes to railway reform, it is essential for policy makers and experts to learn lessons from other countries’ experiences. Based on the background given, this issue aims to understand the lessons from past railway reforms which the sector has experienced under different circumstances. Specifically, besides railway reforms in Europe with a focus on the UK, the issue discusses railway reforms in four other countries: Japan, USA, Russia, and Mexico.

Guest editor of this issue: Fumio Kurosaki fumiokurosaki@itej.or.jp

Download full pdf – Network Industries Quarterly – vol 18 – issue nr 4 – year 2016

Read it online:

[accordion tag=h2 clicktoclose=”true” scroll=”true”]

[accordion-item title=”European Rail Policy – British Experience” id=4 state=closed]

European Rail Policy – British Experience

Chris Nash

Research Professor in the Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds (ITS)

Abstract

Until 1991, European rail policy accepted that rail transport was a natural monopoly provided by a single vertically integrated government owned company providing infrastructure and train operations. Starting in 1991, policy shifted towards the introduction of competition within the rail sector. This note will concentrate on the experience of Britain, whilst pointing out some key differences from other European experience.

Introduction

Until 1991, European rail policy accepted that rail transport was a natural monopoly provided by a single vertically integrated government owned company providing infrastructure and train operations. Legislation required that the rail company be an autonomous unit responsible for its own decision taking and finances. Where the rail company had inherited costs, for instance for pensions that a commercial organisation would not incur, the government should bear them. Where the government imposed public service obligations to provide unprofitable services or charge non commercial fares, the government should compensate the railway company. Otherwise, the railway should operate on a commercial basis.

Starting in 1991, policy shifted towards the introduction of competition within the rail sector. It was recognised that infrastructure was a natural monopoly, but argued that it was possible to have competition between alternative operators over the same infrastructure. EU legislation now requires complete open access for freight and international passenger operators (although some restriction is possible on the carriage of domestic passengers on these trains where this would damage services run under a public service contract). In order to reduce the risk of discrimination, it requires a degree of separation of infrastructure from operations, with separation of decisions on track access charges and capacity allocation from any train operating company and separate accounts. It requires an independent regulator to whom appeals can be made in the case of alleged discrimination. Only now is legislation underway which will require competitive tendering for public service contracts (but with provision for continued direct award of contracts where this process can be justified to an independent authority) and open access for commercial domestic passenger services (subject again to possible limitation where these would compete with services operated under public service contracts).

Already in 1988 Sweden had completely separated rail infrastructure and operations into separate government owned companies and most of Europe has now followed. The alternative which is still permitted is for infrastructure and operations to be separate subsidiaries of the same holding company. This was the model adopted by Germany, Italy, Austria and now France. It is argued by these railways that this permits more efficient planning of investment and use of rail capacity, although this must be done in a way which does not discriminate against other train operators.

Whilst on track competition between freight operators is now widespread in Europe, as noted above neither on track competition nor competition for public service contracts is currently required in the (domestic) passenger sector. However, competition for public service contracts is now the norm in Sweden and is rapidly spreading in Germany; in several other countries it is used for some noncore services. On track competition is also growing with two operators on key routes in Italy, Sweden and Austria and three operators on the most important route in the Czech Republic.

But it is Britain which has taken rail passenger market competition furthest. It no longer has a state owned passenger operator, with virtually all services operated by private companies under franchises awarded by means of competitive tenders. But it also has growing experience of on track competition as a result both of overlapping franchises and of new open access competitors. This note will concentrate on the experience of Britain, whilst pointing out some key differences from other European experience.

Rail reform in Britain

Rail reform in Britain essentially took place in the period 1994-7, although there have been significant further developments since. It has to comply with European Union legislation, although the recent decision by Britain to leave the EU means that, when that is implemented, this constraint may no longer apply.

By 1997, infrastructure was separated from operations and placed in a new company, Railtrack, which was privatised by sale of shares. Freight operations were split into two companies and those companies were sold. Passenger operations were divided into 25 companies and these were privatised by competitive franchising. Passenger rolling stock was placed in three separate leasing companies and these were also sold off. Infrastructure maintenance and renewal was also placed in separate companies and sold.

Thus Britain became the only country in Europe to have completely privatised its railway; elsewhere infrastructure and a large proportion of passenger services have always remained in the hands of publicly owned companies. The logic was that competition would be introduced wherever feasible in the structure, not just for all freight and (largely through competitive tendering) passenger operations but also for the leasing of rolling stock and the maintenance and renewal of infrastructure. The one element of the system that was deemed to be a natural monopoly – the planning and operation of the infrastructure – was to be regulated by a new independent regulatory body as now required by EU legislation.

Yet the success of the British approach cannot be described as other than mixed. Whilst the period since privatisation has seen rapid growth in both freight and passenger traffic (not however mainly due to the reforms), there have been considerable problems relating particularly to the efficiency of the infrastructure manager and the successful working of the franchising system. In what follows we will review experience in each of these areas in turn, before seeking to reach conclusions on the way forward.

The Infrastructure Manager

At first, separation and privatisation of the infrastructure manager seemed to be achieving its objectives, with efficiency improving (Smith and Nash, 2014). However, there were other signs of problems ahead. Firstly, operators, particularly smaller ones, complained that they were totally dependent on a monopoly provider of infrastructure who was unresponsive to their needs. Secondly, and more seriously, there was evidence that the condition of the infrastructure was deteriorating, with an increased incidence of faults including in particular broken rails. Thirdly, the most important upgrading to which Railtrack was contractually committed – that of the West Coast Main Line – was running late and seriously over budget.

Matters came to a head in October 2000, when a broken rail caused a fatal accident on the East Coast Main Line at Hatfield, for which Railtrack and its maintenance contractors were subsequently found to share the blame. Because Railtrack had no adequate record of the state of its assets, the management panicked and imposed severe speed limits until this could be checked and remedial action taken where necessary. The cost of this remedial action, the compensation it had to pay to train operators and the cost of the overrun on the West Coast Main Line upgrade put Railtrack into financial crisis. It appealed to government for a bail-out, but instead the government chose to place it in administration until it could be taken over by a successor company, Network Rail.

From the first, Network Rail was a curious organisation. It took the legal form of a company limited by guarantee; that is, it was a private company but without shareholders. Instead it had members, selected from the industry and the general public. The government guaranteed all its debts and therefore had powers to intervene if it was in financial difficulties. But otherwise the task of ensuring it operated efficiently fell largely on the regulator. It was argued that this was better than an old style nationalised industry, as the regulator could provide an independent view of the extent to which Network Rail could improve its performance in terms of costs and quality of service. But there is little doubt that the real reason for the choice of structure was that it enabled Network Rail’s debt to be regarded as outside the public sector. This was always a controversial issue, however, and in 2014 the British Office of National Statistics decided that in fact Network Rail’s debt should be treated as public sector debt. This led to an immediate change in the position of Network Rail, in that it was required to borrow from the government, its borrowing became subject to limits imposed by the government and the government itself began to seek to influence Network Rail efficiency, raising issues of overlap with the rail regulator. Indeed the government consulted on significant changes to the powers of the regulator, but in the face of serious opposition did not pursue these changes.

As has already been noted, there was a substantial increase in Network Rail expenditure after Hatfield and this continued to grow for several years (Smith and Nash, 2014). This led to serious concern on the part of the regulator; benchmarking studies suggested that Network Rail fell a long way short of the efficiency of the most efficient infrastructure managers in Europe. The regulator set tough targets for cost reduction, and although costs were reduced these targets were not met. By 2009, concern about this and the simultaneous growth of costs of passenger train operators (despite the contracts being let by competitive tendering) led to the McNulty (2011) report into the efficiency of the British rail network.

McNulty concluded that costs were at least 30% higher than they should have been, and that a major reason for this was a misalignment of incentives between the infrastructure manager and train operators. Now Britain had done more to try to overcome this misalignment than any other European country. It had a sophisticated system of track access charges which distinguished between literally hundreds of types of vehicle, designed to reflect the damage that vehicle did to the track given its weight, axleweight, unsprung mass, speed and bogie design (although despite this there had been a tendency to introduce more damaging passenger rolling stock as fleet renewal took place, perhaps as a result of the short time horizons of passenger franchisees – Nash et al, 2014). Elsewhere in Europe, track access charges are much simpler, often depending only on train kilometres with little differentiation by type of train. It also had a performance regime whereby whichever part of the railway system – infrastructure or train operator – caused delays, it had to pay compensation for them. This included delays due to track maintenance and renewal work by Network Rail. Such a performance regime is also now a requirement of European policy but most countries were much slower to introduce one and again tended to make it much simpler.

But McNulty saw other major areas in which the problem of misalignment of incentives had not been tackled. For instance, train operators generally only paid marginal cost for train operations (to the extent that there is a two part tariff for passenger franchisees, there is simply a fixed charge that is passed back to government in terms of the bid level of subsidy or premium in the franchising competition). So train operators had no incentive to assist Network Rail in reducing the total cost of the system, for instance by reducing capacity or quality requirements (for example by deferring renewals) even where this was consistent with their needs. Similarly, they had no incentive to reduce the damage done to services by track maintenance and renewals, for instance by investing in rolling stock and staff training which made diversion rather than bus replacement possible, since they would be fully compensated for increased costs and loss of revenue by Network Rail.

In the meantime, a further financial crisis has hit Network Rail. In the run-up to the 2015 general election, the government announced a big increase in rail investment, including electrification of several of the lines that remained in diesel operation. In practice, the costs and timescales for these investments also turned out to be much greater than the initial Network Rail estimates, leading to no fewer than three reviews of Network Rail being set up during 2015, the most fundamental being the Shaw report (Shaw, 2016). This reiterated the conclusion of McNulty that Network Rail should adopt a more regional structure, with only those activities which really needed to be undertaken nationally remaining at headquarters. The Network Rail regions or lines would have their own accounts facilitating benchmarking, and might even be concessioned to the private sector. McNulty had also concluded that they would need to work more closely with franchisees, possibly even forming joint ventures.

In practice the way forward has been the formation of alliances between the relevant regional management of Network Rail and the franchisee. Usually these have only covered specific activities, but in a couple of cases ‘deep’ alliances have been formed, with a joint management team and a sharing of costs and revenues

Franchising

Unlike other European countries, where franchising is only applied to subsidised services, in Britain virtually all passenger services are franchised, including commercial ones. The main exceptions are Eurostar services to the continent via the Channel Tunnel and the Heathrow Express airport service, plus a small number of other open access services which will be discussed further in the next section.

When passenger services were first franchised, the passenger services of the state owned operator, British Rail, were divided into 25 passenger companies following the internal structure of British Rail at the time. Each company served a specific geographical area and a specific type of service (inter city, London commuter or regional). The company winning the franchise took over this train operating company for the duration of the franchise. Franchises were let typically for 7-10 years, on the basis of the subsidy asked for or the premium offered for each year of the franchise. Minimum levels of service were required and some fares (commuter fares and long distance off peak fares) were regulated. Franchisees were responsible for providing rolling stock, which they usually leased.

However, several of the first round of franchises failed because of the failure to reduce costs as forecast. Subsequently, two successive winners of the East Coast franchise, withdraw early in the franchise because of the failure to achieve the forecast revenue growth. As a result, disincentives for early withdrawal were tightened, with not just a performance bond, which would be surrendered but also more substantial requirements regarding the level of financial support that would be given to the train operating company by its parent company in the event of financial difficulties.

The McNulty report favoured longer franchises, with contractualised commitments to reducing unit costs, as a way of strengthening incentives for cost reduction. However, before these changes could be implemented, the Department for Transport experienced major difficulties with the letting of one of the most important franchises in the country – that for the West Coast Main Line. It was found to have failed to follow correctly its own procedures in awarding the franchise, and as a result the award was withdrawn and bidders compensated.

This led to two further reviews of franchising, one specifically on what changes were needed within the Department for Transport to avoid a repeat of these problems, and a wider review of franchising conducted by Richard Brown. In the meantime the letting of new franchises was halted, and existing franchises extended by direct negotiation.

The Brown report (2015) concluded that franchising should be resumed, but at a manageable pace in terms of the number let each year. Brown took a cautious approach to longer franchises, advocating a return to 7-10 year franchises, with the possibility of extensions up to 15 years, but recognising that there might be a case for longer (or shorter) franchises in specific circumstances. He advocated the government bearing risks which the train operator could not influence, and in particular adjustments in payments if GDP growth did not meet expected levels. He also argued that the penalties for early withdrawal were now so large that they were severely constraining the number of companies who had the financial strength to bid for more than one franchise, or indeed to bid at all, and that they should be eased. He saw a good case for franchising of regional services to be undertaken by regional bodies rather than national government.

This is essentially the approach now being taken to franchising. There are now 11 companies involved in rail franchising in Britain, of which four are government railways from other countries. Most of the rest are private bus companies.

As already noted, in those other countries which franchise rail services this has been confined to unprofitable services. Most franchises have been smaller and unlike in Britain there has been no obligation for the new operator to take over the staff of the former state-owned operator or to maintain its wages and conditions. As a result, it appears that franchising elsewhere has been much more successful in reducing costs.

Open access

Given that even commercial services are franchised, the current approach in Britain to open access for passenger operators to run services without being awarded a franchise is that these should be limited to cases where they are considered to be attracting significant new traffic to the railway rather than simply taking traffic from the franchisee. The regulator is the judge of this. There are currently two open access operators on the East Coast Main Line, both running from London to destinations not served by regular through services by the franchisee. The regulator has approved application for two further open access services, one on the East Coast main line and one on the West. In all cases, the parent of the open access operator is a major operator of franchised services (either Germany Railways or Firstgroup).

Again, this is totally unlike the situation in the other countries allowing open access competition, where commercial operations are still largely handled by the state owned company without competition for a franchise to do so. In those countries there is no explicit protection for the existing operator, although there may be many barriers to entry, such as difficulties in getting access to infrastructure, stations, depots and suitable rolling stock.

In 2016, the British Competition and Markets Authority issued a report advocating a major extension of on track competition either by easing the rules for new commercial operations to enter the market or by revising the franchising process to create more overlapping franchises (there is already some competition between adjacent franchisees who serve the same cities either by different routes or types of service). Ultimately it might be the case that commercial services would be left entirely to open access operators rather than franchised out. It considered that this would improve cost control, service quality and fares.

Conclusions

It will be seen that British experience of rail reform has been far from straightforward; indeed a number of serious problems have emerged. Of these, the most important is the serious cost increases that have occurred. These appear to have a number of causes, including the misalignment of incentives between train operators and infrastructure managers, and the short time horizons of train operators. Possible solutions appear to be the use of longer franchises, deep alliances including revenue and cost sharing between franchisees and Network Rail and the spread of purely commercial open access operations.

In each case, the policy is not without drawbacks. Longer franchises mean longer periods without competition. Deep alliances with the main franchisee may disadvantage freight and other passenger operators over the same tracks. More open access is difficult to accommodate in a railway short of capacity and may lead to a reduction in the quality of integration between different services running over the same tracks.

There is some evidence that the introduction of competition into the passenger sector has been more successful in the other countries that have introduced it, in particular Sweden and Germany in the case of competition for franchises (Nash, C. A., Nilsson J. E. and Link H., 2013) and Italy in the case of on track competition (Croccolo, F., Violi, A., 2013). However, there are significant differences. As noted above, in Sweden and Germany franchises are usually shorter and have more freedom to revise wages and conditions. On track competition in Italy takes place on the new high speed network, which has plenty of spare capacity (except for some problems at terminals), and is competing against a state owned operator that has not had to compete for the right to operate on those routes. With the implementation of the Fourth Railway Package it is likely that there will be a considerable increase in competition both for and in the rail passenger market in the coming years, and more evidence will emerge on what approach works best in different circumstances.

References

Brown, R (2013). “The Brown Review of the Rail Franchising Programme” Cm 8526: London.

Croccolo, F., Violi, A.,( 2013). “New Entry in the Italian High Speed Rail Market.” International Transport Forum. Discussion Paper No. 2013-29, pp. 11–13.

McNulty, Sir R. (2011). “Realising the Potential of GB Rail: Final Independent Report of the Rail Value for Money Study”, London: Department for Transport and Office of Rail Regulation.

Nash, C.A., Smith, A.S.J, Goodall, R., Kudla, N. and Merkert, R. (2014). “Economic Incentives for Innovation: A comparative study of the Rail and Aviation industries (Feasibility Study): Final report for the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB), Funded by the RRUK-A ‘Half Cost Train Initiative’”, January 2014.

Nash, C. A., Nilsson J. E. and Link H. (2013). Comparing Three Models for Introduction of Competition into Railways. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, Volume 47, Part 2, May 2013, pp. 191–206.

Shaw, N. (2016). “The Future Shape and Financing of Network Rail. The Recommendations.” Department for Transport, London.

Smith, A.S.J. and Nash, C.A. (2014). “Rail Efficiency: Cost Research and its Implications for Policy”, International Transport Forum Discussion Paper, 2014: 22, OECD.

[/accordion-item]

[accordion-item title=”Reform of the Japanese National Railways (JNR)” id=3 state=closed]

Reform of the Japanese National Railways (JNR)

Fumio Kurosaki

Senior Researcher, Institute of Transportation Economics (Tokyo)

Introduction

In April 1987, the Japanese National Railways (JNR) experienced the railway reform, and it was divided into a single freight railway and six passenger railways (JRs). This case is recognized as the first case of the railway reform of the nation-wide state-owned railway in the modern history and implemented prior to other countries. Mainly because of the increase of the transport volume, productivity, and sustainable management of those JRs, it is considered as the successful reform of a public enterprise in the country.

Background of the Reform

Since the establishment of JNR as a public enterprise in 1949, JNR had enjoyed the dominant status in the transport sector until the 1950s and had been profitable. However, competition from other transport modes has become severe, and JNR lost its competitive edge. Also, JNR shouldered the burden of construction costs of new lines. Then, JNR ran a deficit in 1964, and the annual deficit continued for many subsequent years. JNR accumulated long-term debt each year, and at the time of JNR reform in 1987, it amounted to 37.1 trillion yen, which was roughly equivalent to the combined national debts of several developing countries. Besides a substantial fall of the JNR’s transport share caused by rapid motorization and development of air transport, JNR Reconstruction Supervision Committee indicated two main reasons for the JNR’s failure.

First, JNR was the public corporation, and this resulted in the following problems.

- The politicians and the government interfered into the JNR’s management. For example, politicians exerted pressure for the construction of unprofitable new lines.

- The JNR’s administration was not autonomous. For example, the budget, personnel, and wages were stipulated by the Diet or cabinet.

- Relationship between managers and workers’ union was collapsed. Labor unions in JNR lost awareness of costs and demanded improved benefits without considering the JNR’s management.

- Business scope was strictly limited. Rigid regulations prevented JNR from expanding its business scope to non-railway activities.

Second, JNR was nation-wide organization, and the unified organizational structure throughout the country caused the following issues.

- The size of organization is beyond the management control. It was difficult for managers to control the monolithic organization appropriately. Then, employee tended to lose loyalty to JNR, and this hindered the effective management.

- The management was standardized. Essential issues such as fare levels, timetables and the location of the station were planned by the headquarters, and local conditions could not be reflected on those plans.

- Since management of JNR was implemented as a nation-wide organization, several divisions were sustained based on irrational reliance. When the reliance had become excess, ineffective divisions could be sustained as well. This hindered the effective management and the revitalization of railway operation.

- Managers and employees lacked the conscious of competition since there was no similar kind of railways in Japan. Although the competition with other modes had become intense, the administration was not oriented to compete with them through flexible management.

In addition to financial difficulties, JNR also faced severe public criticism because of its ineffective management, and JNR reform was obliged to be undertaken as a result. For implementing the JNR reform, it was aimed to solve above issues. Accordingly, it was planned to privatize the organization to solve the issue behind the public enterprise, and it was planned to divide JNR into several companies to solve the issue behind nation-wide monolithic organization.

Outline of the JNR Reform

1) Establishment of JRs

JNR was reformed in April 1987. In this process, the railway network was divided by regions, and six independent passenger companies were established. Although the government agency, the Shinkansen Holding Corporation (SHC), owned the infrastructure of Shinkansen lines at the time of reform, the passenger companies owned the assets of conventional lines. In 1991, the three passenger companies bought the infrastructure of Shinkansen lines from SHC. Thus, regarding the assets built during JNR era, each passenger company owns the infrastructure of both Shinkansen and conventional lines since then.

Facing the JNR reform, it was prospected that the railway operation of the three passenger companies on Japan’s main island (Honshu) would be profitable. Thus, JR East, JR Central, JR West along with JR Freight started their management succeeding the JNR’s liabilities. Then, as noted above, the three companies in Honshu bought the infrastructure of Shinkansen lines. As a result, those four companies beard 14.5 trillion yen as the total liabilities and have been carrying out their management by refunding the allocated liabilities steadily.

In contrast, it was prospected that the railway operation of other three passenger companies on Japan’s island would become unprofitable. Then, the government allocated Management Stabilization Funds to these companies aiming to avoid paying subsidy annually to them and promote their management incentives. At the time of JNR reform, JR Hokkaido, JR Shikoku, JR Kyushu received 682.2, 208.2, 387.7 billion yen respectively, and their management has been sustained by utilizing the Fund’s interest until recently.

Regarding the freight sector, a single nation-wide company (JR Freight) was established since, different from the passenger sector, the general distance of freight transport is much longer and the freight trains usually cross the border among the divided passenger companies. As another distinct characteristic of JNR reform, it was designed so that JR Freight accesses the trunk lines owned by the passenger companies. Behind this design of railway reform, there was a background that freight rail transport had been unprofitable during the history of the JNR. Although it was essential to cut excess cross-subsidy between the passenger and freight sectors and terminate irrational reliance between the two sectors, it was also important to realize the sustainable management of JR Freight. Thus, JR Freight was released from infrastructure maintenance for reducing its operational costs. Also, the track access charges were set as relatively low level, and JR Freight pays “avoidable costs” aiming to shoulder only those inherent to freight rail transport.

2) Issues behind JNR Reform

JNR reform was the one of the most serious political agenda in Japan in 1980s. For implementing the reform, several issues must be solved. For example, unprofitable 83 local lines were separated from JNR/JRs’ network until 1990s to make the management of JRs sustainable. Among the issues, the most serious ones were those about long-term liabilities and surplus personnel.

As noted above, JNR’s long-term liabilities were accumulated to 37.1 trillion yen. To settle the liabilities, the government agency, the JNR Settlement Corporation (JNRSC), was established and succeeded 25.5 trillion yen. JNRSC made efforts to refund the succeeded liabilities by some means such as selling the shares of JRs, selling the land that was not necessarily required for railway operation. Despite its efforts, JNRSC could not refund all the succeeded liabilities and dissolved in 1998. As a result, 13.8 trillion yen was transferred from JNR’s long-term liability to a national debt.

Regarding the surplus personnel, JNR employed 277,020 workers as of April 1986, and it was estimated that there would be approximately 93,000 excess personnel after JNR reform. Thus, the government treated this issue by establishing a Surplus Personnel Reemployment Measures Headquarters and enacting a special law which requested active cooperation from various national sectors to employ them. As a result, the new railway companies reemployed the 203,000 workers and the others changed jobs or retired.

Results of JNR Reform

1) Management of JRs

The results of JNR reform have been outstanding. The newly established JRs could focus their market and started to provide the transport services appropriate for each region. Even in the freight sector, which had been loss-making in JNR era, the serious downturn trend since 1970’s had been changed and the traffic volume (ton-km) has become stable since the reform. As for the passenger sector, since it could terminate the cross-subsidy to the freight sector, it has become possible to re-invest the profit to improve the passenger services. Although the transport volume (passenger-km) decreased 6% in a decade until JNR reform, the trend changed largely and it increased 27% in a next decade after the reform. Furthermore, following the business model of other Japanese private railways, JR passenger companies also commenced the affiliated business actively utilizing and developing the space in and around the stations. Nowadays, especially around large-size stations, it has become common that group firms of JR passenger companies promote various kinds of the affiliated businesses utilizing the external economy of railway operation, and the revenue of these business activities have been increasing.

2) Privatization of 4 JRs

As for the three JR companies in Honshu, their management has been in the black even if they bear the cost of infrastructure and burden of the allocated JNR’s liabilities. As planned, all shares of JR East, JR West, and JR Central have been listed in 2002, 2004, and 2006 respectively. The segment of railway operation of JR Kyushu has been in the red. However, the company increased the revenue through the affiliated businesses and has been in the black as a whole company. Then, all shares of JR Kyushu were also listed in October 2016, and its Management Stabilization Funds were liquidated by paying railway-related expenses such as the advance payment of lease fee for the Shinkansen infrastructure, which was constructed after JNR reform. As shown by these cases, the JR companies improved the rail services and developed the affiliated businesses as well. And they have promoted their businesses based the schemes planned in JNR reform without receiving annual subsidy from the government.

Lessons and Future Challenges

1) Lessons: Factors for the Improvement since the Reform

When we consider the positive performance of JRs, we can conclude the JNR reform has been in success so far. The success can be attributed to mainly privatization and regional division, both of which solved causes of the JNR’s failure as noted above. This section discusses the other essential issues which are distinct from typically EU railways.

First, the passenger railway company operates and manages both infrastructure and operation in Japan. Although there are some lines where the owner of the infrastructure is different from the railway company, the railway company keeps integrated operation even on these lines. Thus, besides few exceptional cases, we can note that the passenger railway operation is integrated on the lines in Japan. And this has been advantageous not only for smooth railway operation but also for coordinated investment into railway systems and promoting the affiliated businesses. In Japan, on-track competition has not been introduced at all, and competitive bidding has been utilized only for limited cases in recent years. Instead, JNR reform also played a role to improve yardstick competition between the railway companies. Thus, managers and employees in the Japanese railways have sufficient motivation to increase the profit as an independent (private) company with three types of competition: 1) competition with other modes of transport, 2) competition between tracks (in some sections), and 3) yardstick competition.

Second, the passenger through-trains are operated with clear separation of operational responsibilities at the border station between the companies. In Japan, through-train passenger services were common among Japanese railways and were also introduced among JRs. However, different from open access in EU countries, each company takes the responsibility for both train operation and infrastructure management, as noted above. In general, drivers change at the border station, and they drive trains on their company’s track only. As this example shows, a fundamental policy in Japanese passenger railway operation is to separate operational responsibilities clearly at the border station, and this has contributed to the smooth, efficient, and safe passenger train operation in Japan.

2) Future Challenges

JNR reform will face 30th anniversary in April 2017. We can say that the management of JR companies has been sustainable so far based on the original scheme planned at the time of reform. Nevertheless, when we consider the change of the transport market up to present and in the future, there are some challenges which the railway sector in Japan has to manage.

Despite the positive rail transport performance in urban area and some inter-city lines, many local lines face severe decline of the number of passengers. Since the population in Japan will decrease in the future especially in the local area, these local lines will become more unprofitable. Certainly, division through JNR reform eliminated excess cross-subsidies between the divided networks. But, some JRs still have large rail network. Thus, if cross-subsidy is continued within the company, even the transport services on the profitable lines will lose competitiveness because of the lack of investment funds.

As for JR Hokkaido and JR Shikoku, of which average passenger density is lower than other JRs, they still own the Management Stabilization Funds and utilize the Fund’s interest to cover the loss of railway operation. However, because of the low-interest rates in the Japanese financial market, the Fund’s interest has not reached the amount that was expected at the time of JNR reform. Thus, the management has been tight particularly in JR Hokkaido in the last few years. If it is decided to sustain the local lines with a limited number of passengers, certain measures, such as vertical separation and PSO contract, should be introduced to gain financial support from the local governments.

References

Fukui, K. (1992) Japanese National Railways Privatization Study: The Experience of Japan and Lessons for Developing Countries, World Bank Discussion Papers, No.172.

Ishida, Y. (2011) Japan, Reforming Railways: Learning from Experience, CER

JRTT (2016) Web Site of Japan Railway Construction, Transport and Technology Agency (JRTT) http://www.jrtt.go.jp (accessed on 9 November 2016)

Kurosaki, F. (2008) An Analysis of Vertical Separation of railways, Thesis for the University of Leeds

MLIT (1996) Transportation White Paper 1996 (Unnyu Hakusho 1996), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

MLIT (2015) Railways in terms of the Figures (Suuji de Miru Tetsudou 2015), Institute for Transport Policy Studies

[/accordion-item]

[accordion-item title=”Institutional Reform of Intercity Railways in the U.S.” id=6 state=closed]

Institutional Reform of Intercity Railways in the U.S.

Louis S. Thompson

Principal at “Thompson, Galenson and Associates”

Abstract

Railway institutional changes in the U.S. since the early 1970s have transformed the sector. Creation of Amtrak removed the burden of passenger losses from the freight railroads and allowed intercity passenger services to stabilize. Deregulation of the private freight railroads put the industry on a stable basis, improving earnings, increasing investment and reducing tariffs to shippers. The future of the sector depends partly on political will to support passenger services and not to re-regulate freight, and partly on the success of projects to establish new passenger services in Florida and California.

Railways employ distinct technologies: steel wheels on steel rails furnishing low rolling resistance; long, thin shape yielding low wind resistance; and, potential for electric traction with higher energy efficiency and lower carbon emissions. Railways can move high volumes within a restricted space and are extremely safe. But, rail has limited flexibility to serve areas outside its immediate reach and is less competitive at shorter distances.

The role of the railway is driven by the railway’s capabilities, but also by its competitors and by the geographic, demographic and institutional framework within which the transport system functions. Autos are more flexible, but use more energy and land space. Trucks are flexible, do not require high volumes and move at higher speeds, but also have higher costs and impact on the environment. Airlines are fastest over long distances, but use much more energy. Above the network is the country’s institutional framework, including policies toward public funding and the mix of public/private roles and the role of regulation.

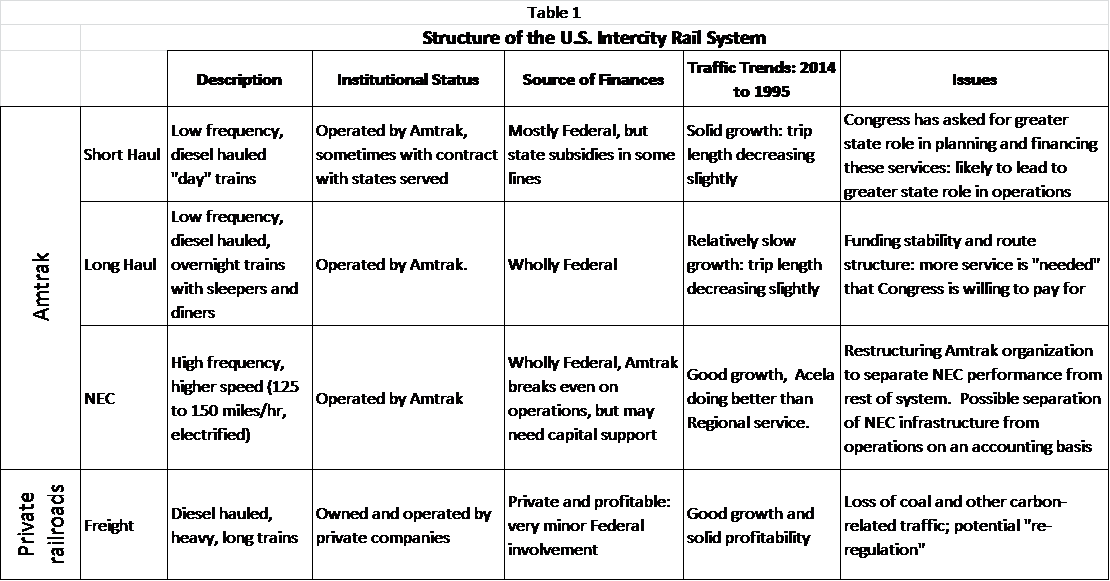

The outcome is a complex pattern of technologies and services. The pattern is never fixed: technologies evolve, governments shift with political currents and the structure of the economy develops. This is especially true of the U.S., partly because of its leading role in development of transport technologies, but also because reliance on competition and private ownership fosters an unusual flexibility to change both in the transport sector and in the economy at large. Table 1 gives an overall picture of the intercity rail system in the U.S.

Railways in the U.S. carry short-haul intercity passengers between closely spaced cities, typically within one state, as well as long-haul intercity passenger services that often operate interstate with sleeper and diner services. At the same time, and often over the same tracks, U.S. railroads haul enormous quantities of freight. Table 2 gives an overall picture of the scale and trends of rail operations of the U.S. rail system.

Intercity passenger services in the U.S. were originally provided by private railroads. Although these services could be sustained before the advent of the automobile, this became more difficult after World War II. The ability of most families to have a car, the construction of the Interstate Highway System and the emergence of the jet airplane destroyed the intercity rail passenger market and, by 1970, passenger losses were seriously weighing on the private freight railroads.

The government’s response was to create Amtrak, a federally owned corporation intended to relieve the freight railroads of all intercity rail passenger service beginning in 1971 and to revitalize passenger service under new management. Over its lifetime Amtrak has undergone continual restructuring and reorganization as Congress and the President have struggled to reach a stable definition of Amtrak’s role and amounts and sources of funding.

Amtrak reports its operations in three lines of business: 25 short-haul “day” services that operate over the tracks of freight railroads (paying access fees), mostly within a single state and mostly with one train/day in each direction though some routes have multiple daily frequencies; 15 long-haul trains, mostly with diners and sleepers and mostly once-daily frequency, all of which operate over the lines of freight railroads and pay access fees; and, the Northeast Corridor between Washington, DC and Boston, MA through New York City where there are 38 higher-speed services and 48 medium speed services daily together carrying about 38% of Amtrak’s passengers and generating 54% of its revenues.

By Amtrak’s accounting, the long haul trains are money losers ($530 million in 2015). The short haul trains appear to be less unprofitable ($86 million in 2015) and the Northeast Corridor trains have an operating profit of about $482 million, though it is not clear what share of the cost of the infrastructure they are carrying (Amtrak, MPS). Amtrak owns and maintains most of the Northeast Corridor infrastructure and charges commuter and freight operators for access. The relative performance of the lines of business is clouded by the fact that many of the short haul trains receive state support (which Amtrak counts as revenue) and Northeast Corridor results are impacted by unclear sharing agreements with local commuter authorities and freight operators.

Whether Amtrak has been a success depends on the point of view. One objective, separating passenger losses from freight finances, was clearly achieved and, in conjunction with freight deregulation, permitted the freight railroads to remain in private hands. The success of revitalizing passenger service was not met as well: Amtrak’s traffic has not grown rapidly and its cost, at $70 billion ($2015), has been high.

The U.S. railroad freight system consists of 7 large (“Class I”) freight railroads, all of which are privately owned, along with 21 smaller “regional” railroads (again all private) and some 546 small “short lines” that are mostly privately owned and operated, though some are owned by state or local authorities. The Class I railroads account for about 70% of the track-miles and 95% of the revenues of the overall U.S. rail system (AAR, 2015).

The U.S. rail freight system is an example of one of the most successful cases of institutional reform in the last four decades. In the early to mid-19th century, the railroads occupied a near-monopoly position in most markets and they were not particularly shy about exploiting their position. This, along with the flamboyant excesses of early rail investors (“Robber Barons”) generated great political opposition. In 1876, the Congress created a regulator (the Interstate Commerce Commission) aimed at reining in the railroads’ economic and political power.

Unfortunately, as often happens with public regulators in the political arena, the objectives were not well defined and were actually perverse in their economic impacts. Over time, the system morphed from limiting monopoly power into limiting railroads’ ability to compete with highways and barges. At the same time, federal and state programs that built highways and waterways without making trucks and barges pay an appropriate share for their use began to weigh heavily on the financial performance of the private rail system. Regulatory policies to force the private railroads to cross-subsidize passenger service out of freight “profits” added insult to injury and, by 1970, much of the system was badly weakened financially.

Congress acted first to create Amtrak in order to remove the passenger support burden from the railways and put it on the federal and state governments where it belonged. Though helpful, this was not enough and by the mid-1970s, most freight railroads in the Northeast were bankrupt. In response, the Congress first nationalized the Northeast rail system and reorganized, rehabilitated and refinanced the system with public money. Then it re-privatized the system (creating Conrail). When it became clear that even this was not enough, the Congress took the final step and deregulated the railroads in 1981 (along with airlines in 1979 and trucking in 1981).

For the freight railroads, deregulation meant that, within very wide limits to control excess earnings and abuse of monopoly power over a single shipper, they could completely control the tariffs and services offered. In particular, railroads could offer contract rates to shippers in which guaranteed tariffs were offered in return for volume commitments, shipper ownership of wagons, railway or shipper investment in specialized facilities and many other terms reflecting a market-driven balance between the benefits and costs available to railway and shipper.

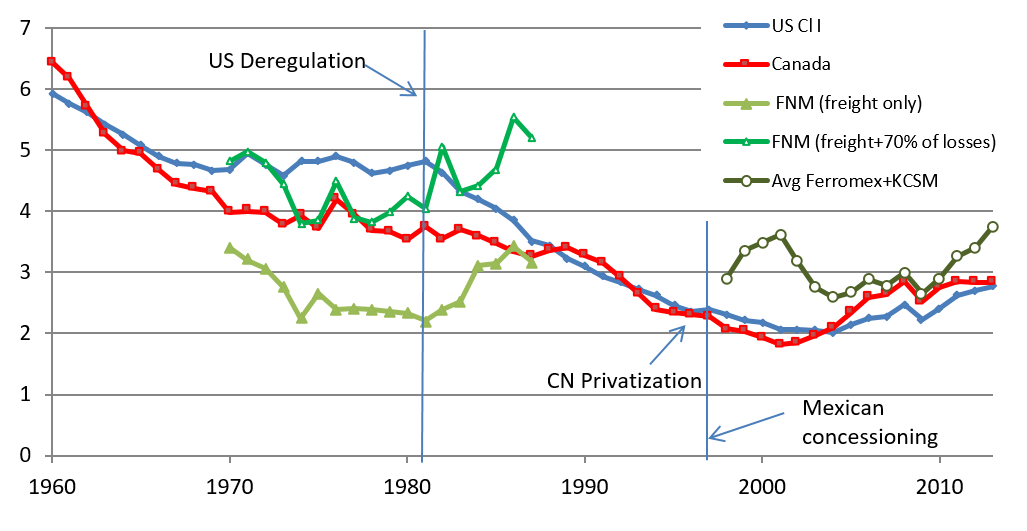

The results of the deregulation of rail freight were remarkable. From inception to about 2004, while traffic (ton-km) grew by 83% and the regulator’s measure of return on investment grew from 3.09% to 8.46%, the average freight tariff in real terms fell by 58%. Although there were complaints from individual shippers (as there always are), there is little doubt that deregulation far exceeded even the most optimistic of expectations.

How did this happen? Deregulation enabled a rapid increase in productivity, mostly because contract rate-making permitted railroads to work much more closely with shippers to offer more flexible and efficient services. Output per employee grew by 434%; output per locomotive (horsepower adjusted) grew by 34%; and, traffic density (ton-miles/mile of line operated) more than tripled: the increase was driven partly by traffic growth, partly by a reduction in the miles of line operated (abandonments were made easier by deregulation), and partly because of voluntarily negotiated multiple use of lines (“trackage rights”) wherein the percentage of tracks with more than one operator grew from 9% in 1981 to 28% in 2015. Over the same period, Class I railroad ownership of freight wagons fell from 66% in 1981 to less than 28% by 2015: this meant that shipper-owned equipment could be more specialized and productive while at the same time relieving railroads of the investment burden.

There were also qualitative changes in the freight system brought about by the freedom that deregulation permitted. For example, container traffic grew from about 2.7 million units in 1990 to nearly 12 million in 2014. Included in this total is traffic for J.B. Hunt, a major trucking company that purchases wholesale capacity from railroads and then markets retail container loads to its customers, many of which do not know (or care) that railroads are involved in the long-haul part of the shipment.

The tariff picture after 2004 has been more mixed because the combination of growth in rail traffic with growing congestion on the U.S. highways (partly caused by inadequate public funding of highway maintenance and construction) meant that the railroads could raise tariffs and they did so, by about 34% through 2014: this was at least partly justified by the need to finance the capacity needed to handle the traffic shifting from roads and the tariffs are still 43% below 1981 levels in real terms. Then, the financial crisis of 2008 caused a drop in traffic from which the rail system has only now fully recovered. With this said, the current picture of the U.S. freight railroads is one of independence, adequate earnings and reasonable future prospects, subject to qualifications discussed below.

The future of passenger services is largely driven by public funding at local, state and federal levels. Unfortunately, the U.S. political system has been increasingly divided over the issue of taxes and effectiveness of governments at all levels. There are no clear prospects for political consensus on the need for passenger service in the near future (if ever). For rail freight, the chief political danger is re-regulation as demanded by various powerful shipper groups or relaxation on truck sizes and weights as demanded by truck lobbyists. Paradoxically, since the freight railroads benefit from the regulatory status quo, political inaction is their friend.

Beyond politics, there are other portents. The need to reduce carbon emissions could be critical. Although powerful political forces continue to deny the fact of climate change for ideological or self-interest reasons, there is a growing consensus that the U.S. must participate in global programs to reduce carbon emissions and the U.S. is increasingly committed by treaty to do so.

The energy efficiency of rail and the ability to use electric traction generated from low carbon sources gives rail an advantage if carbon emissions are traded or taxed. This is not an overwhelming advantage, however, as the economic cost of reducing carbon emissions by investment in rail can often be much higher than alternative programs such as LED lighting or home insulation. Carbon emission reduction is a positive result, but must be combined with other benefits such as time savings, lower tariffs, safety or noise reduction if increased spending on rail passenger service is to be justified.

Carbon reduction cuts both ways for freight. On the one hand, railways are energy efficient and thus would benefit from traffic shifted from less efficient trucks, assuming that carbon is efficiently priced. On the other hand, a large percentage of the world’s carbon-based fuels are transported by rail and any carbon emission reduction program will reduce rail traffic, especially coal. Since coal makes up about 39% of U.S. rail freight traffic, and is one of the most profitable commodities, carbon reduction programs are a threat to U.S. railways unless other technologies, such as carbon capture and sequestration, are implemented.

There are good reasons to expect continued evolution of rail passenger organization in the same direction as in the past few decades. Amtrak short haul lines will increasingly be shifted to a higher share of state financing, which will ultimately cause the states to ask for a greater role in planning and operating the systems. Amtrak has tended to lose competitions for operation or maintenance contracts because of its high costs and rigid work conditions, so Amtrak’s role in short haul services may well shrink. The existing Amtrak long haul lines appear to be in rough equipoise between the Congressional forces wanting service to their state or district and the budgetary forces that are reluctant to pay: except at the margin, little change is likely.

The Northeast Corridor represents about 30% of the U.S. population on 9% of its land area and most resembles areas in Europe and Asia where longer haul, higher speed rail passenger service makes economic sense. Given adequate funding (always difficult), continued upgrading and rehabilitation of the Northeast Corridor would be a good investment. The challenge will be to create a new institutional framework, possibly based on a form of infrastructure separation that would more clearly assign responsibilities for investment and operation among all the commuter, intercity passenger and freight operators that the NEC serves. It seems unlikely that a visionary new Northeast Corridor line serving exclusively high-speed trains can ever be built because of the enormous cost.

Two entirely new intercity passenger services are in prospect. All Aboard Florida is a wholly privately financed, medium-speed service that expects to start service on a three hour schedule on the 235 mile route from Miami to Orlando in 2017. About 50 miles of line between Cocoa, FL, and Orlando International Airport will be on newly constructed tracks: the remainder will be conducted on tracks of the Florida East Coast Railroad, whose parent company is the sponsor of the project. The outcome of the project, especially the ridership actually achieved, will be a significant harbinger for the potential for new private sector rail passenger projects.

The California High-Speed Rail project is the only high-speed rail project under construction in the U.S. The 220 mile/hour system will be built in stages, initially connecting San Francisco with Los Angeles and Anaheim, with connections to Sacramento and San Diego added later. The system is designed to deliver 2 hour 40 minute service between San Francisco and Los Angeles. The cost of the project has been estimated at $64 billion for San Francisco to Los Angeles/Anaheim with service to be initiated in 2028. The California High-Speed Rail Authority intends to manage the planning and construction of the system and then to contract or concession operations to a private operator.

The project has been controversial, partly because construction of a major transportation project in an inhabited (and litigious) environment always engenders opposition. More important, though, is finance. California voters approved a bond issue in 2008 that provided about $9 billion for the system. Federal funds added another $2.9 billion. In addition, 25% of the state’s receipts from its carbon trading program have been dedicated to the project. This is projected to yield around $500 million annually until 2025 when the remainder of the funding through 2050 will be monetized to yield another $5.2 billion. Finally, the Authority projects that the system will be profitable and the expected net revenue stream can be monetized in 2028 and 2029. Even so, accepting the Authority’s medium demand projection leaves an uncovered gap of at least $15 billion possibly covered through new federal grant programs.

References

Amtrak, “Monthly Performance Summary,” (MPS), September 30, 2015.

www.amtrak.com/ccurl/322/821/Amtrak-Monthly-Performance-Report-September-2015-Preliminary-Unaudited.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2016

Association of American Railroads (AAR), “Railroad Facts, 2015 Edition,” Washington, DC

U.S. Surface Transportation Board (STB), “Statistics of Class I Railroads,” Washington, DC. Various years were used to create multi-year data series

[/accordion-item][accordion-item title=”Reform of the railway sector in Russia: achievements and challenges ” id=2 state=closed]

Reform of the railway sector in Russia: achievements and challenges

Alexander Kolik

Professor, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia

Abstract

The Russian railway system has been in the process of reform for 15 years. The introduction of the unique railway market model had solved some problems but numerous challenges still exist

Reform background and preconditions

The Russian railway system is one of the world’s largest. Russell Pittman (2013) calls it “…one of the economic wonders of the 19th, 20th, and 21st century world”. Railways account for more than 85% of freight tonne-kilometers (excluding pipelines) and 27% of passenger-kilometers (Rosstat 2016). Railway transport is the backbone of the entire Russian economy. Many basic national industries (mining, metallurgy, etc.) have no alternative transport mode. It is not a surprise that for decades “railways” and “transport” were actually synonyms in everyday Russian language.

For nearly a decade the industry was not affected by the dramatic socio-economic reforms that started in Russia in 1992. The Railway Ministry (MPS – Ministerstvo Putei Soobschenija) combined the roles of service provider, policy maker, and regulator. It remained a monolithic non-transparent state monopolist amidst the developing market economy.

The declared reason was that the risk of damaging the highly integrated railway system could, in turn, harm not only Russia, but other post-soviet states for which railways had been the essential connecting link.

But in the beginning of the 2000s the enormous investment needs of the industry could not be funded at the expense of operations any more. Loss-making passenger services needed growing internal cross-subsidies. The situation demanded changes. The government recognized that competition, if introduced, could attract private capital, drive cost reduction and improve service level.

Railway reform program and initial steps

The railway reform in Russia started in 2001 after adopting the “Program for Structural Reform in Railway Transport” (Russian Federation Government 2001).

The declared goals of the reform were to introduce competition and facilitate private investment in the industry, improve the service quality, sustainability and safety, and reduce the economic costs of transportation. The program envisaged three phases.

The first phase (2001-2003) was aimed to separate the policy-making and regulatory functions from business management and operations.

To achieve this, a 100% state-owned joint-stock company “Russian Railways” (Rossiiskye Zheleznye Dorogi – RZD) was established. The “policy-making” segment of MPS was integrated into the Ministry of Transport. RZD inherited all the basic assets of MPS, while numerous non-core structures such as hospitals, schools, etc. were divested. Significant staff reduction took place. At the same time, a considerable number of new legal acts were adopted in order to prepare the transition from state‐owned railway monopoly to competitive railway industry.

The second phase of the reform (2003-2005) was aimed at RZD corporate restructuring and further market-oriented legal base improvement.

During this period certain business lines and activities within the company were institutionally and legally separated. More than 40 subsidiaries were established in the segments of container transportation, reefer services, new auto transportation, rolling stock repair, etc. Phasing out of internal cross-subsidizing of passenger operations of the expense of freight started.

In the legal sphere the principle of non-discriminatory access to railway infrastructure was declared, although RZD was still the only railway carrier. New legal acts and modified tariffs encouraged private investment in freight railcars. During this period the segment of so called “wagon operators” was rapidly growing up to eventually become one of the principal components of the Russian railway market model.

The third phase of the reform (2006-2010) was planned to be a period of intensive attraction of private capital to the industry. Some of the RZD subsidiaries were to be privatized. It was planned to create a competitive market for freight transport services and, probably, long haul passenger transportation.

At the same time, within ten years of reform, after all the initial and preparatory steps described above, the model of the future railway market was not clear at all.

Reform model debates

The discussion on the railway reform model had actually begun much earlier than the 2001 Program was adopted. This discussion was far from being academic since it was a time of deep socio-economic transformations that dramatically changed the life of the whole country.

Some of the old-school experts came along with the slogan “Hands off the railways!” They argued that the MPS system, so integral and solid, was capable of surviving through hard times – probably, with a little help from the government. But any serious intervention, they said, will lead to industry collapse and economic disaster.

But the majority agreed on the necessity and inevitability of the reform and discussed the appropriate model to be chosen. The main criteria were “Not to cause economic shocks”, “Not to make irreversible steps”, “Not to destroy the integrity of the system”. It sounded reasonable considering the dominating role of railways in freight transportation.

As is known, international practice provides two main models of competitive railway market: a) competition between vertically-integrated companies (North America) or b) separating the infrastructure management from operations to establish a platform for competition of carriers “on rails” (introduced by the EU “railway” directives).

In the course of discussion only a few voices called for straightforward choice of one of these models. Most of the experts and decision-makers agreed that some special approach was necessary – adequate to historic development of railways and the current economic situation in Russia. In this case the “American” approach of creating several independent, integrated companies to compete with each other was unanimously rejected because it led to immediate “loss of system integrity” (although some international experts admitted the possibility of horizontal separation in the European part of Russia: see, for example (ECMT 2004)). The “European” model was seen as the possible option, but its implementation was meant to be very careful and gradual.

Finally, the following formulation concerning the reform model was included in the text of the Program: “…in the course of the structural reform conditions can be created to make possible the complete organizational separation of infrastructure and operations. The appropriate decision can be taken in the light of international experience”. At the same time, it was stipulated that necessary is “…to preserve the integration of infrastructure with a portion of freight operations, at least during the first years of the reform” (Russian Federation Government 2001).

As for the new competing carriers, the Program said the following: “on the basis of industrial railway transport (on-site railway operators – AK) and certain new-built local railway lines vertically integrated railway companies can be created. On the licensing basis these companies can be given the right to access the public infrastructure to carry out cargo transportation” (Russian Federation Government 2001).

Anyway, the Program was adopted, while there was no clear vision of the market model to be reached at the end. But the practical development of the reform had identified the basic principle of the new railway industry: wagon operators as the main competing market players.

Wagon operators

The first wagon operators arrived on the stage in early 2000s against a background of an acute shortage of railcars. In 1998 the railways had purchased 6680 freight wagons while in 2001 only 104 (Farid Husainov 2012). The MPS, admitting the incapability of investment in the rolling stock, suggested that big shippers should buy railcars for their cargoes in exchange for a tariff discount.

This mechanism was implemented and a growing amount of freight was transported in shippers-owned rolling stock. Soon enough the number of private wagons had exceeded the demand in many industries and the fleet owners started outsourcing their railcar companies.

The wagon operating business turned out to be very profitable due to free tariffs. Besides, wagon operators had no service obligations (unlike public railway that had to serve each registered customer) and they could choose the most attractive commodities and trade lanes. As a result, enormous investments in the wagon operating segment were made not only by shippers but also by independent financial structures as well.

The government was satisfied by the fact that private business was rapidly entering the railway transport. Some observers equated the growing competition between wagon operators to the intramodal competition declared among the reform priorities.

RZD decided to participate in this process. In 2007 the First Cargo Company was established – the RZD-daughter wagon operator with 200 thousand ex-RZD wagons. In 2010 it was followed by the Second Cargo Company (currently – Federal Cargo Company) with 175 thousand freight cars. RZD preserved a small fleet for its internal operating and maintenance needs only.

After all was finished, the freight railway market had acquired the following structure unparalleled worldwide:

- RZD as a single state-owned monopolistic railway carrier, the owner of infrastructure and the long haul locomotives. No wagons in operation. RZD manages and executes transportation, issues waybills and follows a state-regulated tariff. The tariff has commodity classes, is weight and distance based and includes the “infrastructure”, the “locomotive” and the “wagon” components;

- More than 1400 wagon operators with the fleet of 1,6 million railcars offer capacity to customers together with a set of additional services (forwarding, documentation, mediation in relations with RZD, etc.). The wagon operator substracts the wagon component and charges the shipper adding the payment for his additional services.

Passenger transportation

Reforms had affected the passenger transportation as well, and their results vary greatly in different segments of this business.

The reform in the long-distance passenger segment was, probably, the most consistent one. The Federal Passenger Company (FPC) was established in 2009 as a subsidiary of the RZD. FPC owns the passenger wagon fleet (traction and infrastructure services are bought from RZD) and is legally acting as a carrier. At the same time, several independent private carriers occupy a small share of the market (about 5%), competing with FPC on the most popular routes (Moscow – St. Petersburg, Moscow – Nizhny Novgorod, Moscow – Ekaterinburg, etc.).

The economy-class services of FPC are directly government subsidized since the tariffs are regulated. This scheme had replaced the internal freight-to-passenger cross-subsidies within RZD. At the same time, the tariffs for high-class passenger services are deregulated.

The largest share in the structure of the rail passenger traffic (about 90% of passenger-kilometers) belongs to suburban (commuter) segment. It was planned to outsource this activity from RZD and to establish Regional Suburban Companies (RSC) holding the depots, rolling stock, etc. RSCs were to be owned – partly or entirely – by regional authorities. The latter were recommended by the government either to subsidize their RSCs or to set their rates at the “economic level” (Julia Panova, et al. 2014).

But in practice most of the regions could not follow these recommendations. Subsidies would have been an unbearable burden for their budgets while economic levelled suburban tariffs covering the costs would have meant the social shock for millions of passengers.

In most of the regions RSCs act as the formally established administrative structures that are just selling tickets. The assets belong to RZD which is the operator as well. But RZD can’t run this business in full scale since it is formally overtaken by the regions, and the federal subsidies are terminated. Cancelling of suburban trains is common practice now; in certain regions this activity is completely frozen.

In the end of 2012 the new concept of the local passenger railway services was drafted which was aimed to tackle the mentioned problems, first of all, by passing corresponding legislation, but it is not adopted yet. In fact, the reform in suburban segment has effectively failed because of poor economic substantiation and the absence of an adequate legal base.

Reform results and remaining challenges

When the ten-year period of the 2001 Program had elapsed, the government prolonged the reform. “The Target Model of the railway freight market until 2015” was the document defining the further actions for five years. It expired on December 2015 bringing no fundamental changes to the industry. In the absence of any other governmental orders the reform can be formally considered complete.

So what are the main results achieved during these 15 years?

No matter how disappointed can many observers feel with the speed and character of the reforms, it should be admitted that Russian railways had changed dramatically.

Among the positive results it should be mentioned, primarily, that the private capital had entered the industry. About 50 billion USD in comparable prices were attracted (EBRD 2014), which solved the rolling stock shortage problem and gave good incentives to wagon-building.

The first competitive segment in the industry – wagon operating – is successfully developing. Many private wagon operators are ready and eager to develop as full-scale railway carriers.

A reasonable degree of success has been achieved in the long-haul passenger segment where the carrier company is outsourced and independent operators exist.

The policy and regulatory framework was separated from railway operations. A number of legal acts had been developed in order to adapt the industry to market conditions. Particular new institutions (like independent freight carriers) are now envisaged legally, although do not exist in practice. The first timid steps were taken to deregulate both freight and passenger tariffs.

The last but not the least to be mentioned here is that serious shocks were avoided. Railways were functioning sustainably enough.

But the list of unsolved problems is even longer.

There is still no competition in the freight transportation sector. RZD, being the monopolist here, has no incentives to improve services and decrease costs.

Freight tariffs – even in their regulated part – are growing faster than the main shippers’ prices (indexes 2014 to 2002 are 349% and 320% correspondingly) and faster than the trucking freight rates (indexes 2014 to 2002 are 349% and 270% correspondingly. All the evaluations are related to 2014 to eliminate the influence of the economic crisis of 2015. Data: Rosstat 2016). It means that one of the main declared goals – to reduce the economic costs of transportation – is not reached.

The service quality is not improving. Cargo delivery speed is low (2002 – 290 km/day, 2013 – 223 km/day. Data: RZD 2016). Freight railway services are not available for many potential “unprofitable” shippers who are simply ignored by wagon operators.

As a result, railways are losing freight in favor of road transport. The freight turnover index 2014 to 2007 is 10% for railways and 19% for trucking (Rosstat 2016).

The reform in the socially sensitive suburban segment should be recognized as a complete failure.

Obviously, there are still many challenges to be tackled. It appears that three main lessons should be learned to move forward.

- The scale and economic importance of Russian railway system probably justify the careful and slow conversion. But, if so, the more important is the definite action plan. Unfortunately, the reform program had set out clear enough goals but did not contain a clear enough roadmap. Many steps in the course of the reform were done as a response to current market situation rather than according to the long-term strategy.

- The best results were achieved in wagon operation – the segment that was fully open to market forces. It does not mean that total privatizing is the best decision but indicates the main vector of the reform strategy: steadily opening the industry to competition.

- Some experts argue that the current crisis situation is not the best time for changes. The Institute of Natural Monopolies Research (IPEM) – the Russian research center that develops recommendations often reflecting the opinion of the “reform headquarters” – confirms that the renewed reform strategy is necessary. But “…at the same time, in the current crisis conditions, it is appropriate that this document should be aimed at “restoring order” and current problems solution, rather than at fundamental transformation” (IPEM 2016).

This mistake should not be committed. The reforms should not be frozen under any circumstances.

References

EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) (2014), Russian Railway Reform Programme. Working Paper (London: EBRD)

ECMT (European Conference of Ministers of Transport), 2004. Regulatory Reform of Railways in Russia (Paris: ECMT).

Husainov, Farid. (2012), Economicheskie Reformi na Zheleznodorozhnom Transporte (The Economic Reforms on the Railway Transport) (Moscow: Nauka Publishers)

IPEM (The Institute of Natural Monopolies Research) (2016), Analytic Report ‘On the 15-th anniversary of the structural reform of the railway transport in Russian Federation’ (Moscow: IPEM)

Panova J., Korovyakovsky E., and Volkova E. (2014), ‘Development of commuter and long-distance passenger traffic in Russia’, Russian Journal of Logistics and Transport Management, Vol.1, No.1: 3-14.

Pittman, R. (2013), ‘Blame the Switchman? Russian Railways Restructuring After Ten Years’ in M.Alexeev, S.Weber, The Oxford handbook of Russian Economy (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 490-527.

Rosstat – Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2016), accessed 31 May 2016

Russian Federation Government (2001), ‘Resolution of 18.05.2001 No. 384 ”On the program for structural reform of the railway transport”’, accessed 3 June 2016

RZD Russian Railways. Official site of the company (2016), accessed 8 June 2016.

[/accordion-item][accordion-item title=”Regulation, competition and performance of Mexico’s freight railways” id=5 state=closed]

Regulation, competition and performance of Mexico’s freight railways

Stephen Perkins

Head of Research and Policy Analysis at OECD-International Transport Forum

Abstract

Mexico restructured its railways in 1995, creating a number of vertically integrated freight rail concessions. These enjoy exclusive rights to serve their territories, structured geographically to ensure competition to serve key markets and complemented by rights of access to specific parts of each other’s networks. The trackage rights have not developed to the full extent foreseen in 1995, fuelling claims by some shippers that they are insufficiently protected from potential monopoly pricing abuse, leading to proposals from Congress to introduce open access provisions across the network. This paper examines the case for change in the regulation of competition based on a review of the performance and efficiency of the Mexican freight railway system today and examines options for enhancing competition.

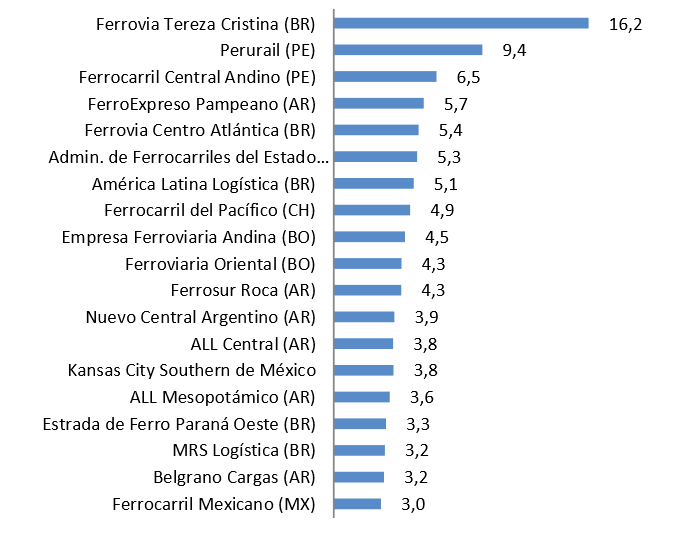

1. Introduction