Written by Marie Vandendriessche

This Topic of the Month will zoom in on the EU’s Energy Union, and particularly a novel part of it: the Governance regulation proposed by the Commission in November 2016, which is currently traveling along the legislative pipeline. To understand this new regulation, some context is first needed. In this first post, we will focus on the birth of the Energy Union, showing what critically distinguishes it from previous EU energy policy.

The EU’s Energy Union was born on July 15, 2014, when Jean-Claude Juncker delivered his inaugural speech to the European Parliament in Strasbourg and outlined the ten policy priorities for the Commission he would soon lead. As MEP Claude Turmes decribes in his book Transition énergétique: Une chance pour l’Europe, EU parliamentarians looked up in surprise when they heard the incoming Commission president use the term ‘Energy Union’ to describe one of those priorities.

The term was not new. A few months earlier, Donald Tusk, then Polish prime minister, had called for an ‘energy union’ as a reaction to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the security of gas supply concerns that the annexation and subsequent friction had rekindled. Yet some of the policies Tusk was suggesting, such as “a single European body charged with buying [Russia’s] gas,” would make for a difficult fit with Europe’s traditional policy framework.

As it turned out, Juncker had loaned the Tusk’s term, but used it to baptize a rather different baby. Whereas the Polish PM had focused primarily on security of supply while simultaneously keeping his country’s energy priorities (particularly domestic coal) in mind, Juncker’s Energy Union concept included not only security of supply considerations but also policies on renewables, energy efficiency, and the completion of the internal market. It was, in effect, a reorganization of the EU’s energy policy and its relation to climate policy.

Paradoxically, energy policy has been one of the slower areas to develop in the European Union, despite the Union’s roots, which lie, in part, in two energy-related international organizations: the European Coal and Steel Community and Euratom. It took until the late eighties for the European Community to consider applying its single market approach to energy, and until 1996 for the market liberalization and integration strategy to take hold. By 2009, three legislative packages were supporting this strategy.

By 2014, however, it had become clear that more action would be necessary. On the one hand, security of supply concerns had returned – particularly in gas. In 2006 and 2009, Russia had cut off gas supply to Ukraine, with consequent effects for a number of European states, such as Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea and a renewed gas dispute between Gazprom and Ukraine, member states importing around 90% of their gas from Russia, such as Bulgaria and Slovakia, became worried once again.

On the other hand, energy and climate change policies in the EU were crossing paths with increasing frequency and leading to fraught situations. The Commission’s traditional liberalization agenda in energy was bumping up against a stark increase in national regulation and policy measures. Yet member states had, in many cases, put those policy measures into place precisely in order to meet EU climate change mitigation goals that required the implementation of specific technologies (such as renewables). To add to the messy situation, the instrument that was meant to bridge climate and energy policy through market forces (the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme) was producing carbon prices far too low to provide the type of signals that the market required.

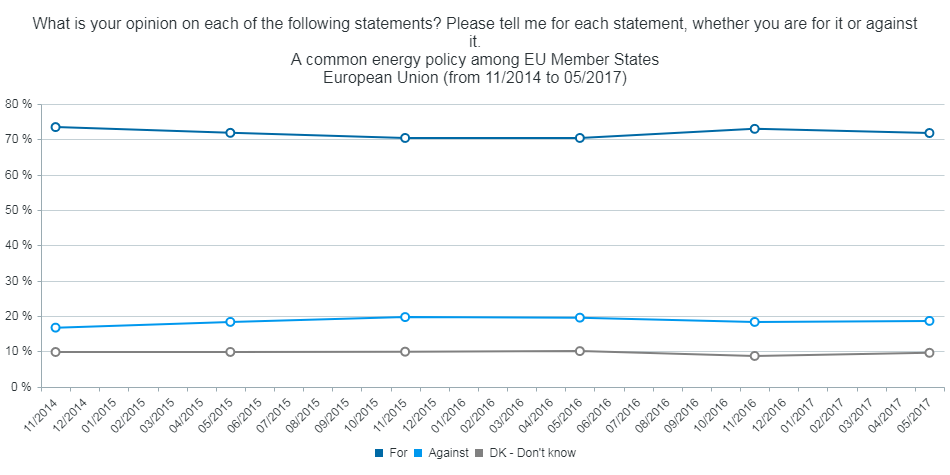

Progress on energy policy at the EU level was thus necessary – but it was also desired. 2014 saw many of the EU’s member states and citizens in a rather Eurosceptic mood. Support for the European project was in decline, and political parties with Eurosceptic mindsets were on the rise. Yet energy provided a rare area of agreement,[1] which the incoming Juncker Commission seized: as the graph below demonstrates, support for a common energy policy among EU citizens has consistently been high, at 70% or above.

Source: Eurobarometer

Moreover, the policy provided a roof all member states could initially see themselves under. The Central and Eastern European states felt their Russia-related security of supply concerns could be addressed under this concept, and many of the northern member states saw the value of a broad roof which could cover and interconnect energy and climate policy areas.

With the appointment of Slovakia’s Maroš Šefčovič as Vice-President for the Energy Union and Spain’s Arias Cañete as Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy, work was started to develop the Energy Union concept further. By February 25, 2015, a clearer outline materialized, in the shape of the Commission Communication A Framework Strategy for a Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy. The Energy Union, which aimed to deliver greater energy security, sustainability and competitiveness, was to be made up of “five mutually-reinforcing and closely interrelated dimensions”:

-

Energy security, solidarity and trust

-

A fully integrated European energy market

-

Energy efficiency contributing to moderation of demand

-

Decarbonising the economy

-

Research, Innovation and Competitiveness

Herein lies a fundamental innovation of the Energy Union: in its interrelated, holistic approach, the strategy constitutes an attempt to push past the silo mentality that has traditionally characterized the EU’s energy policy. The Energy Union was to be a broad, holistic framework encompassing many issue areas, with a medium- to long-term outlook.

The combination of (a) this silo-breaking approach, along with (b) the EU’s new 2030 climate and energy objectives (which were finalized as the Energy Union strategy was developed), and (c) the upcoming Paris process under the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) track created the need for a blueprint capable of coordinating and ensuring coherence between the policy measures being taken at various levels (EU and member state level). This blueprint was Governance – the topic we will address in next week’s post.

[1] (Keay & Buchan, 2015)

References

- European Commission. (2017). Public opinion Eurobarometer interactive. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/getChart/chartType/lineChart//themeKy/29/groupKy/182/savFile/646

- Keay, M. & Buchan, D. (2015). Europe’s Energy Union: A problem of governance. Retrieved from Oxford Institute for Energy Studies website: https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Europes-Energy-Union-a-problem-of-governance.pdf

- Turmes, C. (2017). Transition énergétique: Une chance pour l’Europe. Paris: Les Petits Matins.

- Vandendriessche, M., Saz-Carranza, A. & Glachant, J.-M. (2017). The Governance of the EU’s Energy Union: Bridging the Gap? [Working paper]. Retrieved from European University Institute website: http://cadmus.eui.eu//handle/1814/48325